Everyone Knows Rikers Island Must Close, But That Doesn't Mean It Will

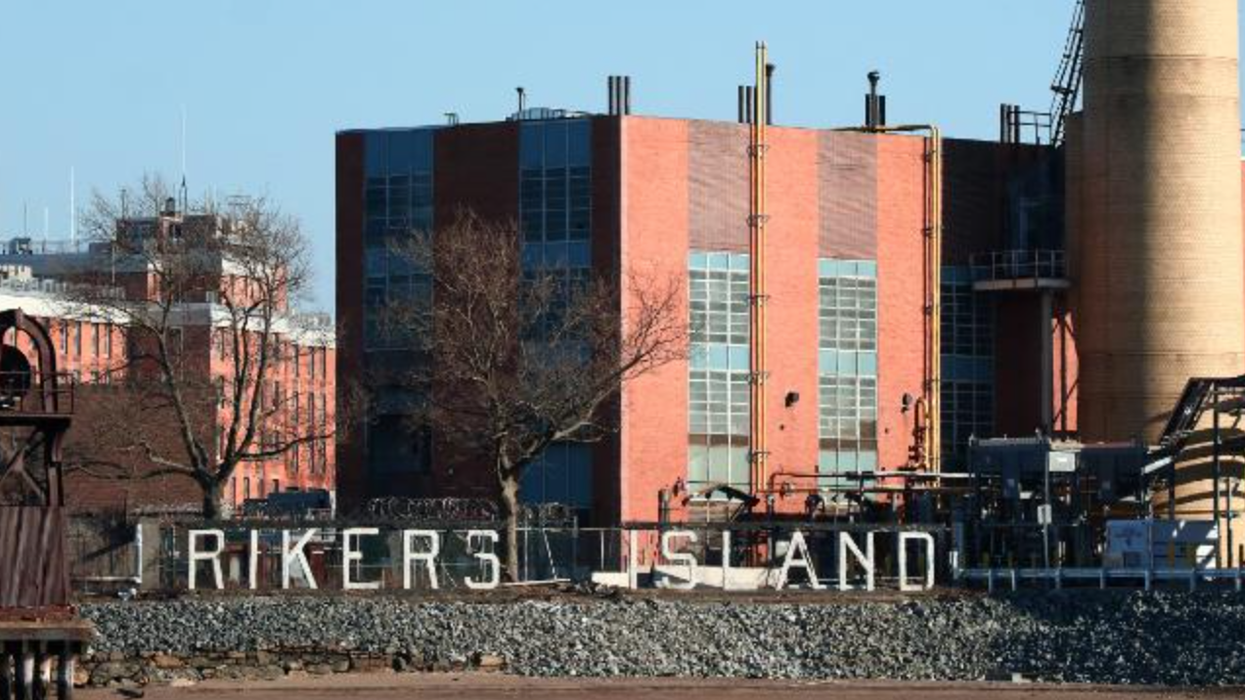

Rikers Island

No one’s going to close Rikers Island.

After a 2017 report from the Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform — also known as the Lippman Commission, a committee tasked with assessing problems at the New York City jail headed by former Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman — insisted that Rikers Island should cease to exist, the New York City Council voted in 2019 to close the jail by 2026, but that date has been moved back even further, to 2027.

Rikers conditions have worsened since that City Council decision. Sixteen detainees perished in 2021, overtired officers inadvertsently released a man accused of murder, and a captain who watched an inmate hang himself was charged with criminally negligent homicide. A judge lowered the bond for a defendant accused of attempted murder because other detainees had beaten him so severely that the judge wasn’t convinced he wasn’t going to be murdered himself. Thousands of detainees are suing over a lack of medical care, a situation so slow to be remedied that lawyers recommended this week that the city be fined $500,000.

As many advocates have pointed out, the Rikers shutdown needs to be speeded up but nothing has come of that, despite the fact that New York City elected a new tough-on-crime mayor who, even with his punitive and carceral inclinations, concedes that Rikers has to go.

It seemed like a harbinger of closures to come when the Board of Correction moved female and transgender detainees to state prisons upstate in October because of the staffing crisis. But no, they were moved back to Rikers last month, ostensibly because over 1000 guards returned to work, not because conditions had improved materially.

For all intents and purposes, Rikers is closed. It’s hardly operational. The detainees run the place — literally.

When a prison or jail reaches a certain point of dysfunction, there’s no improvement, no more investigation needed. Governors and administrators are admitting as much; in 2021 they announced three major prison closures. Last August, the Bureau of Prisons announced that the Metropolitan Correctional Center (MCC), the federal detention center where Jeffrey Epstein died in July 2019, would shutter because a gun had appeared inside, along with cellphones, drugs. That contraband, combined with complaints about a lack of COVID precautions, was enough for Department of Justice officials to throw up their hands and shut it down.

Days later, a federal prison, US Penitentiary Atlanta, was revealed to be in the process of closing, after investigations uncovered misconduct by guards that had corrupted the entire system; staff had smuggled a gun there, too, along with drugs and other contraband. Security had become so lax that inmates were leaving through a hole in a fence, heading to local restaurants and returning.

Last June, New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy decided to close the Edna Mahan Correctional Facility based on a report that women endured from physical and sexual abuse from staff. Edna Mahan is a small facility — fewer than 400 women — which means that abuse is harder to hide. Indeed, abuse reigned there, in the open, for years. Murphy hasn’t closed Edna Mahan just yet but he’s appointed a board of experts to oversee the closure.

Neither MCC, nor USP Atlanta nor Edna Mahan compete with Rikers’ record of human rights abuses and dysfunction and none of them will take a decade to close.

The endless debate over closing Rikers might paint prison and jail closures as momentous events but they’re not. Prisons close often. The state of New York will turn out the lights in six facilities this year alone. Another closed ahead of schedule in Connecticut and Gov. Ned Lamont threw in two more closures. Illinois is mulling a partial closure. Between 2007 and 2013, 31 states closed 120 prisons.

But cost savings motivated those closings. The more recent closures are different because they concede that these facilities are so bad that no justification exists for continuing to house people in them. That’s why the City Council voted to close Rikers. But people still languish there.

The lesson on Rikers’ isn’t the fecklessness of local government. It’s that abolition isn’t as radical as it seems.

The concept of abolition strikes fear in the public, much the way the slogan “Defund the police” does because it calls to mind moratorium, decarceration, desistance and a boomeranging of the crime rate.

But that’s the wrong way to think about prison abolition. The right way is this: Abolition is eliminating what we do now and replacing it with something unrecognizable.

At this point, replacing Rikers Island with something unrecognizable would be a facility with employees who don’t skip work for four to eight months. One without sexual violence. One where food is not only edible, but rather simply served to the mouths expecting it.

It’s true the closing of Rikers Island waits on the completion of new, replacement jail complexes. Considering that process of accepting bids from construction companies commenced late last year, almost three years after the decision to close “Torture Island.” New York construction is notorious for delays and cost overruns. 2011 was the projected completion date for New York’s East Side Access extension of the Long Island Railroad; it’s still not done. To think that construction will be completed in the next five years is overly sanguine, to say the least. And a lot can happen in those five years.

The need for more space is an insufficient excuse for keeping people in the jail complex, especially after administrators in the federal system moved incarcerees out immediately last year. When the constitutional right to be free of cruel and unusual punishment is in play, no serious public servant would wait a decade to remove people from unacceptable living conditions.

Columnist Leonard Pitts, Jr. wrote that “If Sandy Hook didn't change gun laws, nothing will.” Pitts was right; almost 10 years after an unstable gun enthusiast gunned down 20 second graders, sensible gun legislation eludes us.

Rikers is the Sandy Hook of correctional crises. That the jail complex hasn’t been closed already while human rights abuses abound means nothing will precipitate its demise.

Stop looking for closure. It’s not coming.

Chandra Bozelko did time in a maximum-security facility in Connecticut. While inside she became the first incarcerated person with a regular byline in a publication outside of the facility. Her “Prison Diaries" column ran in The New Haven Independent, and she later established a blog under the same name that earned several professional awards. Her columns now appear regularly in The National Memo.

- Dispatch From Deadly Rikers Island: “It Looks Like a Slave Ship in ... ›

- New York's Rikers Island prison is nearly controlled by the prisoners ... ›

- 15 Rikers Inmates Died in 2021. These Are Their Stories. ›

- Rikers Island, Harvey Weinstein's new home, is a byword for prison ... ›

- New York's infamous Rikers Island jail is to close - BBC News ›

- Inside Rikers: Dysfunction, Lawlessness and Detainees in Control ... ›

- Photos inside Rikers Island expose hellish, deadly conditions ›