Who Smuggles Drugs And Weapons Into Prisons? It's An Inside Job

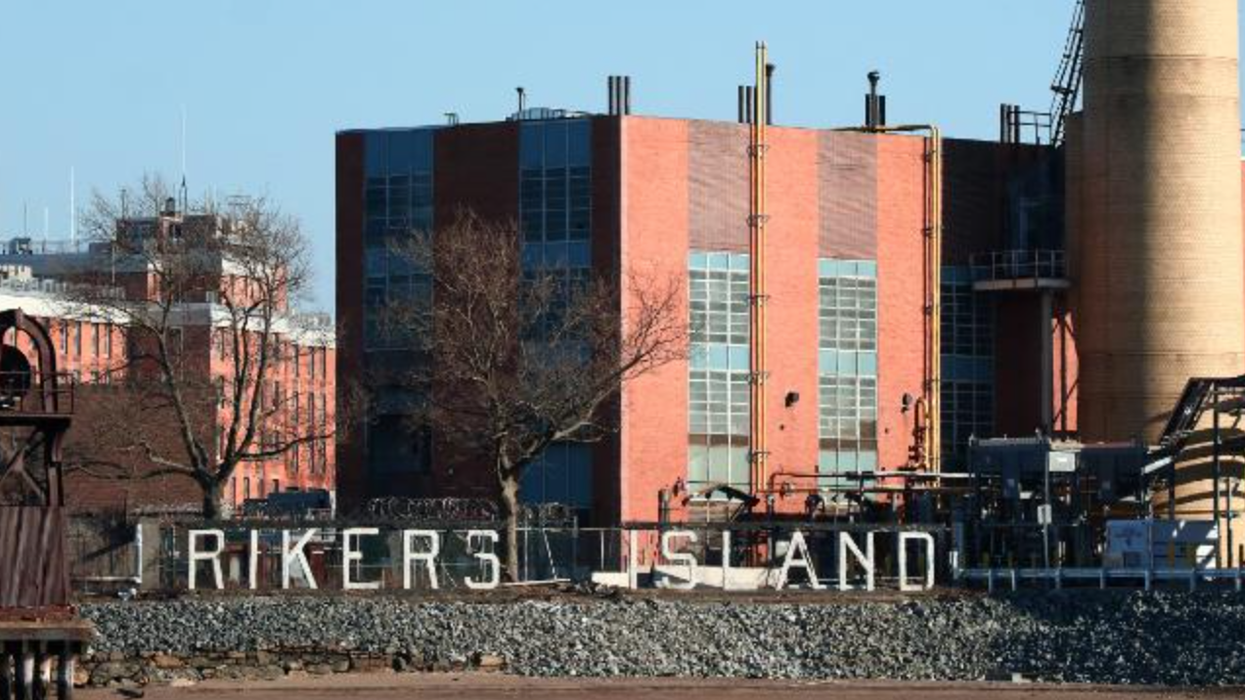

Doctors at Elmhurst Hospital in Queens, New York pronounced Michael Nieves, a 40 year old detainee on Rikers Island, dead on August 31, 2022. Nieves had been suspended between life and death since an ambulance brought him from the New York City jail days before. Nieves had slit his own throat and bled out for at least 10 minutes — as jail staffers looked on and did nothing. A video camera captured the entire tragedy.

The New York City Department of Correction has suspended the staffers, two officers and a captain; accountability awaits. The most shocking aspect of what happened isn’t the disregard for life — that’s pretty commonplace — but the fact that this has become a suicide story and not a smuggling one.

A common perception of contraband and smuggling involves outsiders secretly squeezing items through tiny spaces. But that’s not the rule. Most of the time, smuggling’s an inside job, sometimes of goods that no one would identify as prohibited. Anyone who puts something banned into an inmate's hands is a smuggler.

The New York Times has reported that Nieves was actually given the razor as if that makes his possession of it lawful. A razor intended for shaving but used for suicide is contraband; in prisons and jails, anything used for a purpose that wasn’t intended bears that label.

But the larger point, which should go without saying, is that no one in the PACE Center where Nieves was housed — Rikers Island’s intensive psychiatric inpatient unit — should have been allowed to touch a blade of any type. It should be contraband even if it was used for shaving. This isn’t just a story of inaction. It’s a story of unauthorized goods.

Studying smuggling is a challenge. There’s no way to count the number of times contraband is passed — only the number of times someone is caught is numerable — so no one knows exactly how much illegal passing in prisons is initiated by employees.

But the novel coronavirus taught us that it’s a lot. The pandemic acid-tested prison security; every state and the federal Bureau of Prisons suspended in-person, full contact visits when the crisis started. The only people with contact with the outside were people who worked there.

But the flow of contraband barely stopped. The number of drug seizures in Virginia prisons dropped from 967 in 2019 to 871 in 2020. If visitors introduced contraband in a significant way, the reduction should have been more substantial since visits were stopped on March 16, 2020, canceled as a COVID-19 protection. In Connecticut a search turned up marijuana and a cell phone in February 2021 even though contact with the outside had been on hold since the previous March.

In Texas prisons, where an anti-contraband initiative had started before the prisons closed to visitors, staff found drugs 2297 times, only four fewer than the 2301 drug interdictions in 2019, and even though the number of people incarcerated decreased by about 16 percent.

Smuggling isn’t always as clandestine as it seems. Some employees just walk in with it. Department of Justice Inspector General Michael Horowitz sent Michael Carvajal, the then-Director of the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), an urgent memo last year stating that guards were avoiding being searched when appearing for work.

Carvajal was recently replaced by Colette Peters, the former director of Oregon’s state prisons, but the Senate Judiciary Committee plans on holding another hearing about the failures of the BOP during his tenure when Congress is back in session.

Until such an airing of the ways items land in inmate hands, the federal prison guards union is lobbying to make the number of contraband interdictions the basis for the Bureau of Prisons’ budget — without any irony. So they could bolster their own funding and salaries by bringing in more prohibited goods. An email to the union’s president, Shane Fausey, requesting comment on this position was not returned.

As Nieves' recent story shows, guards freely giving inmates what they’re not supposed to have — either items they brought in or on-site materials — isn’t without consequence. The number of non-COVID deaths in prisons and jails from 2020 to the present time is still being calculated; that data would reveal the human cost of staffer smuggling. Before the pandemic, deaths by drugs and alcohol increased 139 percent between 2016 and 2018 and not because of increased prison populations; the number of inmates barely budged while deaths shot up.

Smuggling problems will be solved only by oversight and there’s almost none of it, even though most everyone agrees it’s needed.

Last month, Families Against Mandatory Minimums, an organization dedicated to creating “a more fair and effective justice system that respects our American values of individual accountability and dignity while keeping our communities safe” released the first ever public poll on prison oversight. While the public may not be entirely sympathetic to what inmates experience, they believe that prisons are too loose. Eighty-two percent of survey respondents said we need independent oversight for prisons and jails.

The people polled by FAMM didn’t equivocate; 73 percent of them think “prisons should be inspected by professionals who are independent of the prison system they are inspecting,” 68 percent plainly reported that they don't “trust government agencies to investigate their own problems and honestly report on them,” and almost all of them think that there should be sufficient staffing, authority and access to provide the needed oversight.

Prison oversight shouldn’t be that hard to build if so much of the general public supports it. But an overarching overseer is hard to establish, mostly because such a bunker mentality grips the facilities. The inmates want to blame the guards and the guards want to see the inmates to face consequences. It doesn’t really matter why.

And that’s not oversight’s game. “The point of oversight is not to find out who did something wrong and hold them accountable, it's to prevent these problems," said FAMM’s president, Kevin Ring in an interview.

That mentality makes contraband smuggling an almost intractable problem since no one’s innocent in the contraband racket, no matter who does the smuggling. Recognizing employees as a source of dangerous contraband doesn’t absolve the incarcerated population. Staff bring in drugs and weapons because there’s a demand for it and inmates or their families are willing to pay; they’re not doing it for free.

Similarly, recognizing outsiders as purveyors of the prohibited doesn’t let prison employees off the hook, either. Contraband sneaks in when they’re not looking. And they’re always supposed to be looking. That’s why they’re paid to work there.

Indeed, looking is exactly what the two officers and a captain did while Michael Nieves lay exsanguinating. The cause of his death wasn’t so much their failure to act but their provision of the death instrument in the first place — and the fact that no one above them was watching to prevent that.

Chandra Bozelko did time in a maximum-security facility in Connecticut. While inside she became the first incarcerated person with a regular byline in a publication outside of the facility. Her “Prison Diaries" column ran in The New Haven Independent, and she later established a blog under the same name that earned several professional awards. Her columns now appear regularly in The National Memo.