Are We Forever Captives of America’s Forever Wars?

Reprinted with permission from TomDispatch

As August ended, American troops completed their withdrawal from Afghanistan, almost 20 years after they first arrived. On the formal date of withdrawal, however, President Biden insisted that “over-the-horizon capabilities” (airpower and Special Operations forces, for example) would remain available for use anytime. “[W]e can strike terrorists and targets without American boots on the ground, very few if needed,” he explained, dispensing immediately with any notion of a true peace.

But beyond expectations of continued violence in Afghanistan, there was an even greater obstacle to officially ending the war there: the fact that it was part of a never-ending, far larger conflict originally called the Global War on Terror (in caps), then the plain-old lower-cased war on terror, and finally — as public opinion here soured on it — America’s “forever wars.”

As we face the future, it’s time to finally focus on ending, formally and in every other way, that disastrous larger war. It’s time to acknowledge in the most concrete ways imaginable that the post-9/11 war on terror, of which the bombing and invasion of Afghanistan was the opening salvo, warrants a final sunset.

True, security experts like to point out that the threat of global Islamist terrorism is still of pressing — and in many areas, increasing — concern. ISIS and al-Qaeda are reportedly again on the rise in the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa.

Nonetheless, the place where the war on terror truly needs to end is right here in this country. From the beginning, its scope, as defined in Washington, was arguably limitless and the extralegal institutions it helped create, as well as its numerous departures from the rule of law, would prove disastrous for this country. In other words, it’s time for America to withdraw not just from Afghanistan (or Iraq or Syria or Somalia) but, metaphorically speaking at least, from this country, too. It’s time for the war on terror to truly come to an end.

With that goal in mind, three developments could signal that its time has possibly come, even if no formal declaration of such an end is ever made. In all three areas, there have recently been signs of progress (though, sadly, regress as well).

Repeal Of The 2001 AUMF

First and foremost, Congress needs to repeal its disastrous 2001 Authorization for the Use of Force (AUMF) passed — with Representative Barbara Lee’s single “no” vote — after the attacks of 9/11. Over the last 20 years, it would prove foundational in allowing the U.S. military to be used globally in essentially any way a president wanted.

That AUMF was written without mention of a specific enemy or geographical specificity of any kind when it came to possible theaters of operation and without the slightest reference to what the end of such hostilities might look like. As a result, it bestowed on the president the power to use force when, where, and however he wanted in fighting the war on terror without the need to further consult Congress. Employed initially to root out al-Qaeda and defeat the Taliban in Afghanistan, it has been used over the last two decades to fight in at least 19 countries in the Greater Middle East, Africa, and Asia. Its repeal is almost unimaginably overdue.

In fact, in the early months of the Biden presidency, Congress began to make some efforts to do just that. The goal, in the words of White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki, was to “to ensure that the authorizations for the use of military force currently on the books are replaced with a narrow and specific framework that will ensure we can protect Americans from terrorist threats while ending the forever wars.”

The momentum for repealing and replacing that AUMF was soon stalled, however, by the messy, chaotic and dangerous exit from Afghanistan. Those in Congress and elsewhere in Washington opposed to its repeal began to argue vociferously that the very way America’s Afghan campaign had collapsed and the Biden policy of over-the-horizon strikes mandated its continuance.

At the moment, some efforts towards repeal again seem to be gaining momentum, with the focus now on the more modest goal of simply reducing the blanket authority the authorization still allows a president to make war as he pleases, while ensuring that Congress has a say in any future decisions on using force abroad. As Senator Chris Murphy (D-CT), an advocate for rethinking presidential war powers generally, has put the matter, “If you’re taking strikes in Somalia, come to Congress and get an authorization for it. If you want to be involved in hostilities in Somalia for the next five years, come and explain why that’s necessary and come and get an explicit authorization.”

One thing is guaranteed, even two decades after the disastrous war on terror began, it will be an uphill battle in Congress to alter or repeal that initial forever AUMF that has endlessly validated our forever wars. But if the end of the war on terror as we’ve known it is ever to occur, it’s an imperative act.

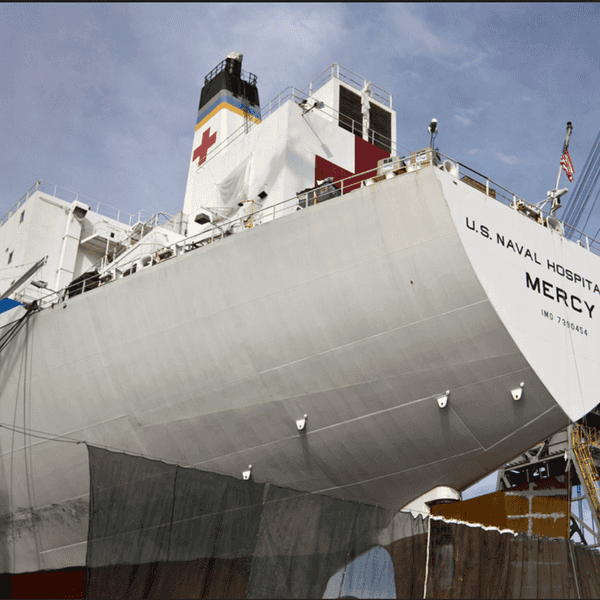

Closing Gitmo

A second essential act to signal the end of the war on terror would, of course, be the closing of that offshore essence of injustice, the prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba (aka Gitmo) that the Bush administration set up so long ago. That war on terror detention facility on the island of Cuba was opened in January 2002. As it approaches its 20th anniversary, the approximately 780 detainees it once held, under the grimmest of circumstances, have been whittled down to 39.

Closing Guantánamo would remove a central symbol of America’s war-on-terror policies when it came to detention, interrogation, and torture. Today, that facility holds two main groups of detainees — 12 whose cases belong to the military commissions (2 have been convicted and sentenced, 10 await trial) and 27 who, after all these years, are still being held without charge — the truest “forever prisoners” of the war on terror, so labelled by Miami Herald (now New York Times) reporter Carol Rosenberg nearly a decade ago.

Through diplomacy — by promising safety to the detainees and security to the United States should signs of recidivist behavior appear — the Biden administration could arrange the release of the prisoners in that second group to other countries and radically reduce the forever-prison population. They could be transferred abroad, including even Abu Zubaydah, the first prisoner tortured under the CIA’s auspices, a detainee whom the Agency insisted, “should remain incommunicado for the remainder of his life.”

The military commissions responsible for the other group of detainees, including the five charged with the 9/11 attacks, pose a different kind of problem. In the 15 years since the start of those congressionally created commissions, there have been a total of eight convictions, six through guilty pleas, four of them later overturned. Trying such cases, even offshore of the American justice system, has proven remarkably problematic. The prosecutions have been plagued by the fact those defendants were tortured at CIA black sites and that confessions or witness testimony produced under torture is forbidden in the military commissions process.

The inadmissibility of such material, along with numerous examples of the government’s mishandling of evidence, its violations of correct court procedure, and even its spying on the meetings of defense attorneys with their clients, has turned those commissions into a virtual Mobius strip of litigation and so a judicial nightmare. As Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) put it in a recent impassioned plea for Gitmo’s closure, “Military commissions are not the answer… We need to trust our system of justice,” he said. “America’s failures in Guantanamo must not be passed on to another administration or to another Congress.”

As Durbin’s comments and the scheduling of a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on closure set for December 7th indicate, some headway has perhaps been made toward that end. Early in his presidency, Joe Biden (mindful certainly of Barack Obama’s unrealized executive order on Day One of his presidency calling for the closure of Gitmo within a year) expressed his intention to shut down that prison by the end of his first term in office. He then commissioned the National Security Council to study just how to do it.

In addition, the Biden administration has more than doubled the number of detainees cleared to be released and transferred to other countries, while the military tribunals for all four pending cases have restarted after a hiatus imposed by Covid-19 restrictions. So, too, the long-delayed sentencing hearing of Pakistani detainee Majid Kahn, who pleaded guilty more than nine years ago, finally took place in October.

So, once again, some progress is being made, but as long as Gitmo remains open, our own homemade version of the war on terror will live on.

Redefining the Threat

Another admittedly grim sign that the post-9/11 war on terror could finally fade away is the pivot of attention in this country to other, far more pressing threats on a planet in danger and in the midst of a desperate and devastating pandemic. Notably, on the 20th anniversary of those attacks, even former President George W. Bush, whose administration launched the war on terror and its ills, acknowledged a shift in the country’s threat matrix: “[W]e have seen growing evidence that the dangers to our country can come not only across borders, but from violence that gathers within.”

He then made it clear that he wasn’t referring to homegrown jihadists, but to those who, on January 6 so notoriously busted into the Capitol building, threatening the vice president and other politicians of both parties -- as well as other American extremists. “There is,” he asserted, “little cultural overlap between violent extremists abroad and violent extremists at home.”

As the former president’s remarks suggested, even as the war on terror straggles on, in this country the application of the word “terrorism” has decidedly turned elsewhere — namely, to violent domestic extremists who espouse a white nationalist ideology. By the end of January 6, the news media were already beginning to refer to the assault on lawmakers in the Capitol as “terrorism” and the attackers as “terrorists.” In the months since, law enforcement has ramped up its efforts against such white-supremacist terrorists.

As FBI Director Chris Wray testified to Congress in September, “There is no doubt about it, today’s threat is different from what it was 20 years ago… That’s why, over the last year and a half, the FBI has pushed even more resources to our domestic terrorism investigations.” He then added, “Now, 9/11 was 20 years ago. But for us at the FBI, as I know it does for my colleagues here with me, it represents a danger we focus on every day. And make no mistake, the danger is real.” Nonetheless, his remarks suggested that a page was indeed being turned, with global terrorism no longer being the ultimate threat to American national security.

The Director of National Intelligence’s 2021 Annual Threat Analysis noted no less bluntly that other dangers warrant more attention than global terrorism. Her report emphasized the far larger threats posed by climate change, the pandemic, and potential great-power rivalries.

Each of these potential pivots suggest the possible end of a war on terror whose casualties include essential aspects of democracy and on which this country squandered almost inconceivable sums of money while constantly widening the theater for the use of force. It’s time to withdraw the ever-expansive war powers Congress gave the president, end indefinite detention at Gitmo, and acknowledge that a shift in priorities is already occurring right under our noses on an ever more imperiled planet. Perhaps then Americans could turn to short-term and long-term priorities that might truly improve the health and sustainability of this nation.

Copyright 2021 Karen J. Greenberg

Karen J. Greenberg, a TomDispatch regular, is the director of the Center on National Security at Fordham Law and author of the newly published Subtle Tools: The Dismantling of Democracy from the War on Terror to Donald Trump (Princeton University Press). Julia Tedesco helped with research for this piece.