Be cautious about recession predictions.

After consulting their models of the American economy, many political naysayers and Wall Street economists are shouting “A recession is coming! A recession is coming!”

Should we trust these projections, which dominate major news reports on the economy? Count me a skeptic, given what the economic performance data show and the conflicted interests of commercial economists.

More jobs and more pay are the opposite of what the word ‘recession’ implies: “a significant, widespread and prolonged downturn in economic activity.”

In a piece typical of news articles last week, CNN reported:

“Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan believes a US recession is the ‘most likely outcome’ of the Fed’s aggressive rate hike regime meant to curb inflation. He joins a growing chorus of economists predicting imminent economic downturn.”

Then, without attribution, CNN added, “His views are particularly important” because he was Fed chair from 1987 to 2007 under Presidents Reagan, Clinton, and both Bushes.

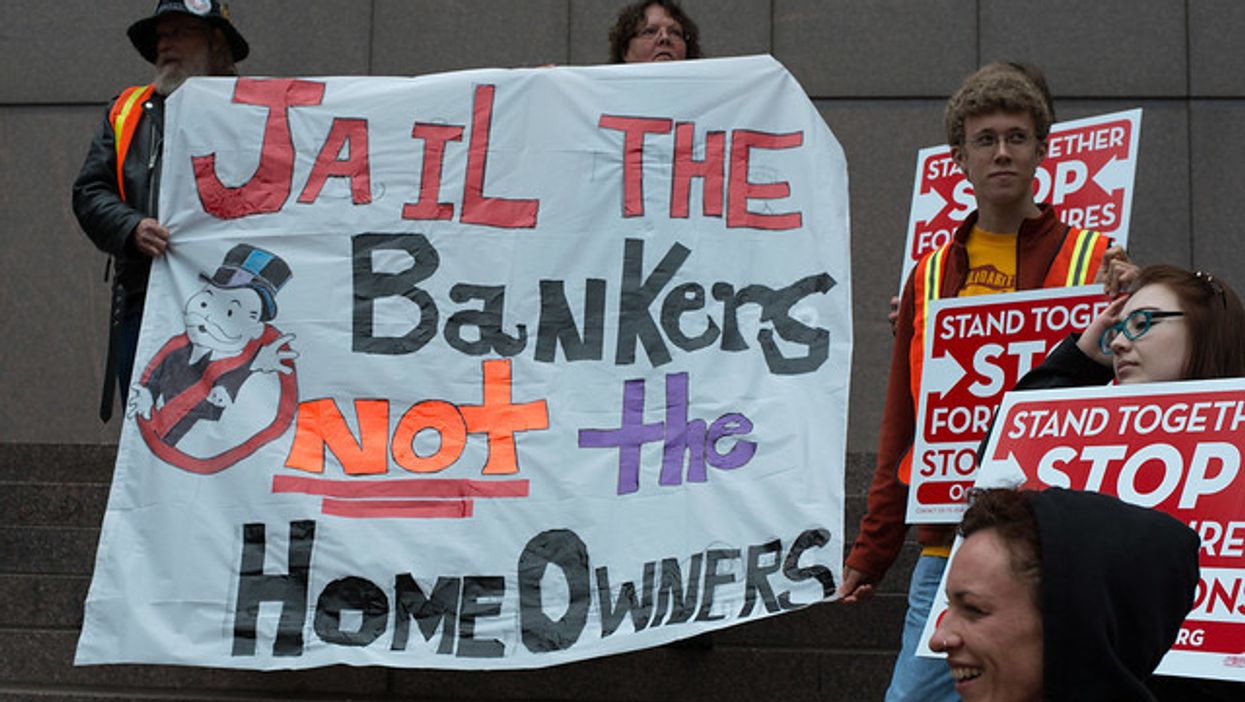

Unmentioned by CNN and others: Greenspan couldn’t foresee the mortgage market collapse that led to the Great Recession in late 2007, the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression.

That’s amazing because Greenspan, now 96, cultivated an image as a clear-eyed and profound student of economic statistics. So how did he miss years of economic red lights flashing that housing prices were headed for a collapse? It was so evident that I told my New York Times editors about the problem in 2003 and then twice found a way to write about it even though it was far beyond my beat covering taxes.

In weighing Greenspan’s prognostications, remember that Ayn “Love Is Immoral” Rand trusted him to be the executor of her estate. Greenspan adored the views of Rand, who taught that altruism is a vice, selfishness a virtue, and who wrote a novel glorifying a criminal who blows up a building because it offended his aesthetics.

Greenspan’s views are, technically and philosophically, on the fringe, yet he gets treated like a centrist.

Key Indicators

That said, how is our economy doing? Let’s examine some key indicators.

The economy added a healthy 233,000 jobs in December.

Employers created more than four and a half million jobs in 2022. That’s an average of 375,000 new jobs per month, almost twice the rate of jobs growth during the Trump Administration’s pre-pandemic years.

Indeed, 2022 was the second-best year ever for job growth. The best year was 2021, but much of that was due to our coming out of the worst of the pandemic, which Donald “inject bleach” Trump badly mismanaged, pushing the jobless rate to almost 15 percent. Most of those discharged performed manual work. People who do intellectual work mostly continued working.

For context, consider job growth under Barack Obama and Trump.

President George W. Bush’s laissez-faire banking policies produced the Great Recession, so we’ll ignore the economic results he bequeathed to Obama.Then, startingg in October 2010, when the economy turned around, Obama averaged 201,600 new jobs per month for six years.

Trump, before the pandemic, averaged just 191,100 jobs added. That’s five percent less per month than Obama and barely half of Biden’s 2022 monthly average.

Voluntarily Quitting

How about job quits? The level at which people voluntarily leave their job says a lot about expectations that they will or already have found new work, often at better pay or under better conditions. People who see a recession looming usually stay put, even in a job they hate.

Each month starting in July, more than four million workers quit their jobs voluntarily. The November quit rate was a robust 2.7 percent or 1 in 37 jobs, although that’s down from the three percent rate a year earlier.

Very Low Jobless Rate

How about unemployment? The jobless rate last month was 3.5 percent under the most widely used measure.

That’s the lowest recorded level of joblessness since World War II save the slightly lower 3.4 percent rate in May 1969 when Vietnam War and NASA spending were boosting the economy, and early Boomers were entering the job market en masse without driving up the jobless rate.

Trump’s average pre-pandemic jobless rate was 3.9 percent though he hit 3.5 percent for three months shortly before the Pandemic began in early 2020.

There is an alternative and broader measure of unemployment, known as U-6 or Bureau of Labor Statistics Table A-15.

The U-6 measure counts people working part-time because they can’t find full-time employment, or are only marginally part of the workforce, or have temporarily given up trying to find work. These marginal workers, whose economic lives are filled with stress and misery, are not central to whether the economy grows or shrinks, but their numbers tell a deeper story about job quality.

The U-6 rate was 6.5 percent in December, down from 7.3 percent a year earlier. However, that doesn’t seem to suggest that a recession is at hand.

Inflation Abating

How about rising prices? While inflation is about 7.1 percent above a year ago, that isn’t the story of the last half year.

Month-over-month inflation peaked at 1.3 percent in June. Then it dropped to zero in July and 0.1 percent in August. Inflation rose to 0.4 percent in September and October. It fell back to 0.1 percent in November. The December numbers should come out around January 13.

Inflation may be whipped, although it could roar back. But for now, its withering

The decent inflationary trend appears to have grown from the pandemic when demand for goods and services fell sharply, and global supply chain problems bedeviled businesses from toy sellers to carmakers. Remember all those acres of parking lots with shiny new cars and trucks that could not be sold until computer chips arrived from Asia? And those shipping containers piled high in ports awaiting trucks to haul them away?

Those bottlenecks have been eliminated or considerably eased through White House efforts to improve coordination and cooperation between merchant sailors, stevedores, teamsters, local port, truck, and railroad managers, and the companies that employ them all.

Still, high energy and food prices continue to bedevil most Americans. Fossil fuels are a major component in food prices. It takes lots of fuel to make fertilizers to grow crops, machines to plant and harvest them, and trucks to berry foodstuffs to grocery stores nationwide.

Overall Economic Growth

How about economic growth measured by Gross Domestic Product or GDP?

There was a lot of ill-informed talk of a recession last summer because GDP was slightly negative for the year’s first half.

But the National Bureau of Economic Research’s Business Economic Cycle Dating Committee, which calls economic contractions and expansions, didn’t call it a recession, partly because the number of jobs kept growing, as did incomes. More jobs and more pay are the opposite of what the word recession implies: “a significant, widespread, and prolonged downturn in economic activity.”

We don’t have the full 2022 data yet, but the federal Bureau of Economic Analysis shows overall economic growth, not contraction in the first nine months of 2022.

By the way, Trump’s economy was slowly sinking before the pandemic, as DCReport advised readers in October 2020.

Pump Price Plummets

And what of inflation, much in the news this year?

The best news is that the national average price of gasoline has plummeted from a high of $5.11 in early June to $3.77 recently. That’s $1.34 less per gallon, a stunning 26 percent decline, not that it made much of a splash on front pages and broadcast news programs.

The sharp drop in the price of gasoline came despite Vladimir Putin’s February invasion of Ukraine which disrupted worldwide oil and grain markets and may yet lead to mass starvation in Syria and parts of North Africa that rely on Ukrainian wheat. The Biden Administration imposed severe price caps on Russian oil via shipping insurance. At the same time, the president released 180 million barrels of oil from the American Strategic Petroleum Reserve to help knock down prices at the pump.

That 180 million barrels is roughly how much oil America burns every ten days, but as is often the case in economics small changes in supply or demand can prompt big changes in price, as our coverage of electrify market manipulations has shown.

Because the Democratic Biden Administration sold oil at about $89 a barrel and will buy replacement oil at about $70 a barrel, the government is expected to turn a profit of more than $3 billion on actions that sharply lowered gasoline prices. Talk about win-win government economic policies.

An inflationary threat that may emerge is tied to rising sales of what two decades ago were called Osama Wagons—gas-guzzling trucks and SUVs that help sustain Middle East dictatorships.

Trade Deficit Shrinks

Trade numbers are also improving under Biden Administration policies, although there was a brief and severe rise in the trade deficit months ago.

During Trump’s first 23 months in office his disastrous and mismanaged trade war with China played a key role in the monthly trade deficit ballooning by 26 percent, federal Bureau of Economic Analysis data show.

The trade deficit, or surplus, comes in two parts. The first and larger measures the value of goods we buy from overseas versus what we sell to foreigners. The second measure is business services we buy from foreigners or sell them.

Our perennial surplus of exported services slightly offsets a perennial and much larger deficit in goods. President Biden has made cutting reliance on overseas manufacturers—especially for computer chips and other high-value, high-tech products—a top priority.

As of November, the deficit is down 3.6 percent compared to when Biden took office two years ago.

Mortgages and Paychecks

Another good sign, and a longer-term trend, is the falling share of personal income going to interest and principal payments on mortgages.

At the end of 2007, as the Great Recession began, Federal Reserve data showed 7.2 percent of personal income went to mortgage principal and interest. Now it’s less than four percent, with a slight uptick last year as the Federal Reserve under Chairman Jerome Powell, a Trump appointee, raised the interest rates it controls.

Americans owe about $12 Trillion in mortgage debt, down almost a fifth since the start of the Great Recession once inflation is considered.

So why do so many people feel so much economic pain?

The median weekly wage—half earn more, half less—is the same now as at the end of 2019 after taking inflation into account.

So why is the median not moving much?

Because a rapidly growing share of wages and salaries goes to executives and others paid more than $1 million per year while rank-and-file workers mostly lack unions and thus lack bargaining power.

Million Dollar Paychecks

In 2020 an eye-popping 82% of all pay raises went to the very thin and well-compensated slice of workers making $1 million or more.

That fell to 29% in 2021. However, the million-and-up club enjoyed average raises of $840,000 each while full-time workers making up to $250,000 got only $1,600. That’s a ratio of $500 to $1.

Also in 2021, the poorest-paid 60 million workers collectively made less than the best-paid 237,000, more than 500 of whom averaged about $151 million, my annual analysis of Social Security Administration payroll data shows.

The million-dollar and up pay club now collects almost seven percent of all wages and salaries, up from two percent in inflation-adjusted data from 1991. The number of these high-paid workers has exploded from 191 in 1991 to 237,000 three decades later in 2021. Last year the number of million-dollar-plus jobs grew 95 times faster than jobs overall.

Recession Risks

So, are we likely to fall into a recession, as Greenspan and many Wall Street economists warn?

The honest answer is we don’t know. As Yankees catcher Yogi Berra said, “it’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”

If the Fed raises interest rates too high or too fast, it could so discourage executives and entrepreneurs that they go on a capital strike, halting the new investment that is crucial to job creation. Then again higher interest rates may also draw more capital into the United States, further strengthening the dollar against other currencies.

When the dollar is high relative to other currencies, it makes what we import cheap, while other countries are burdened with high prices to purchase our goods and services.

The greenback has been riding very high for the past two years. My wife and I vacationed in New Zealand (beautiful, fascinating, and friendly) this fall. Our greenbacks were worth $1.78 against the Kiwi dollar. In Australia, the exchange rate was above $1.60. The story is similar worldwide.

My view on the chance of a recession: bringing back jobs from Taiwan and China, especially microchips and related high-tech manufacturing, will be a long-term boon to the American economy with some immediate effects.

If Biden succeeds in his goal of making America the go-to country for high-quality, high-tech manufacturing the American economic future will be bright. It will also enrich investors more than workers unless the union movement or a proxy for it becomes a major player in economic decision-making.

And as for the policies of the Fed?

It’s independent so you can’t do anything about how its regional governors vote on interest rates and whether money is hard or easy. But the notion that a recession is certain or even likely seems out there, at least for now.

Reprinted with permission from DC Report.