'Venezuelifying' America: Don't Cross The Dictator Or He Will Destroy You

So federal prosecutors have opened a criminal investigation into Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve chair. In his statement in response, Powell, to his credit, didn’t dignify the obviously spurious accusations by protesting his innocence. Instead, he went right to the heart of the matter:

This new threat is not about my testimony last June or about the renovation of the Federal Reserve buildings. It is not about Congress’s oversight role; the Fed through testimony and other public disclosures made every effort to keep Congress informed about the renovation project. Those are pretexts. The threat of criminal charges is a consequence of the Federal Reserve setting interest rates based on our best assessment of what will serve the public, rather than following the preferences of the President.

This is about whether the Fed will be able to continue to set interest rates based on evidence and economic conditions—or whether instead monetary policy will be directed by political pressure or intimidation.

Indeed. Surely nobody at the now completely corrupt Department of Justice really believes that Powell has committed any crimes, other than the crime of not doing Donald Trump’s bidding. This is all about intimidation, not just of Powell, but of everyone at the Fed.

I’ll get to the implications for the Fed and the economy in a minute, but let me first say what Powell can’t: This isn’t just about the Fed. It’s part of a broader assault on anyone who doesn’t go along with Trump’s agenda. At the top of this post I’ve put Powell’s picture next to that of Renee Nicole Good, who was killed by ICE last week, because the attack on Powell and Good’s murder are part of the same story: Trump and his minions have zero tolerance for dissent. No matter who you are, if you stand up to them they will try to ruin your life any way they can, up to and including shooting you in the face.

Given this horrifying reality, it almost feels wrong to talk about the economic consequences of an attack on Fed independence. But these consequences are part of the picture.

So, what does the Fed do, and why is it quasi-independent? I published a primer about that last summer, but here’s the short version:

The Fed is America’s “central bank,” which means, roughly speaking, that it controls the U.S. money supply. This control in turn allows the Fed to set the level of short-term interest rates, a powerful tool for managing the economy.

Why put this tool in the hands of technocrats rather than directly under the control of the president? Because cutting interest rates is easy and pleasant — too easy and too pleasant. Unlike stimulating the economy with higher spending or lower taxes, expansionary monetary policy doesn’t require drafting and passing legislation. All it takes is a phone call to the open market desk in New York, which buys Treasury bills from banks to push market interest rates down. And lower interest rates feel good for a while.

This creates an obvious temptation for the White House to push interest rates down, especially when an election is looming. Yet excessively easy money can lead to inflation. That’s a lesson the United States learned after 1972, when a compliant Fed kept rates low to help Richard Nixon win reelection, setting the stage for years of stagflation.

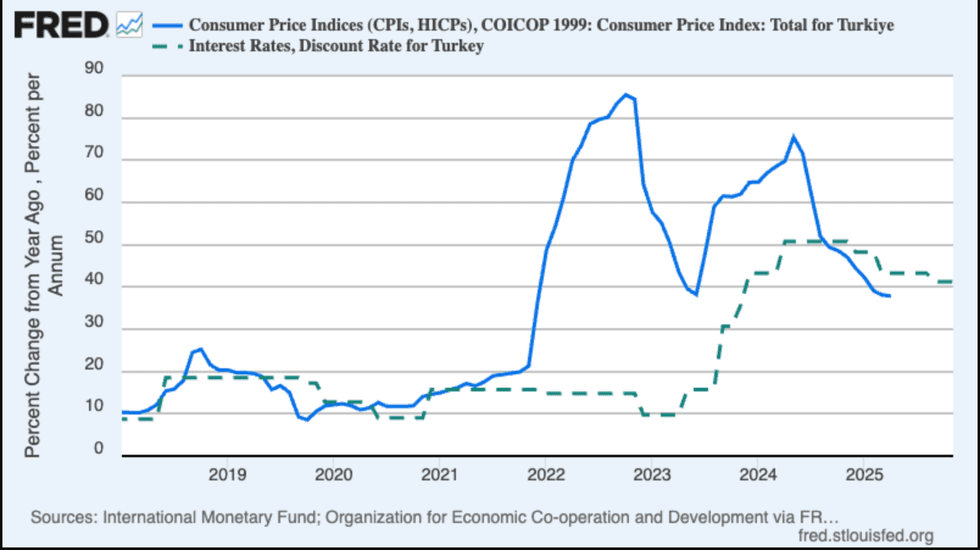

Recent experience in Turkey offers an even stronger lesson. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Turkey’s authoritarian, Trump-like president, forced Turkey’s central bank to keep rates down in the face of rising inflation. The result was that inflation (the solid blue line in the chart below) eventually rose above 80 percent:

Before the Great Depression, many countries avoided inflationary monetary policy by pegging their currencies to gold. The gold standard, however, was too inflexible. In fact, the “golden fetters” it imposed played a major role in deepening the Depression.

How, then, can nations limit the temptations of easy money while preserving the flexibility to deal with crises? The answer, adopted by the United States and many other nations, is to put the central bank under the direct control of technocrats, not politicians. Such “independent” central banks are ultimately accountable to elected officials, but they’re insulated from short-run political pressure.

This system doesn’t work perfectly, because even technocrats are human and sometimes get it wrong. But experience shows that central bank independence works much better than letting monetary policy be politicized, especially when the politicians in question are greedy and don’t understand economics — in other words, when they’re like Donald Trump.

Yesterday a who’s who of former Fed chairs and other former top economic officials issued a statement denouncing the weaponization of the Justice Department against Powell, saying that

This is how monetary policy is made in emerging markets with weak institutions, with highly negative consequences for inflation and the functioning of their economies more broadly. It has no place in the United States whose greatest strength is the rule of law, which is at the foundation of our economic success.

I wish they had been able, just this once, to put aside Fedspeak and use plain language, but let me translate: “emerging markets with weak institutions” means Third World nations like, for example, Venezuela — or, as Trump would say, shithole countries.

Over the weekend, as it happens, Trump declared himself the “acting president of Venezuela,” which he definitely is not. But he is Venezuelifying the United States.

May I say, by the way, that every investor and businessperson who backed Trump or tried to accommodate him once he won should be looking in the mirror and asking why they helped enable this catastrophe. For none of what Trump is doing now is a surprise to people who paid attention.

The irony here is that the effort to intimidate the Fed is likely to backfire on Trump, in three ways.

First, in the near term the Fed will be especially reluctant to cut rates, even if doing so might make sense, lest it seem as if intimidation is working. This reluctance will persist even after Trump chooses a new Fed chair, because interest rates are set by a committee, not an individual, and most of the relevant committee aren’t Trump appointees.

Second, even a politicized central bank can only reduce short-term interest rates temporarily. As inflation rises, the bank will eventually be forced to raise rates higher than they were at the beginning. Look back at the chart for Turkey, above: Erdogan initially pushed the short-term interest rate (the green dotted line) down, but in the face of exploding inflation rate the bank was eventually forced to raise rates to more than 50 percent.

Finally, attacking the Fed’s independence could push long-term interest rates — which are the rates that matter for the economy — higher, not lower, even in the short run. Why? Because bond investors understand that political pressure on the Fed will eventually mean higher short-term interest rates. And long-term rates mostly reflect expectations about the future rather than current short-term rates.

Indeed, although long-term rates didn’t move much after the attack on Powell was revealed, they actually rose slightly.

However, even if Trump understood that his attack on the Fed’s independence will backfire, he would still be going after Powell, because he is less interested in achieving policy results than he is in punishing anyone who crosses him. Powell had the temerity to insist on doing his job rather than prostrating himself at Trump’s feet. So he must suffer — personally.

If top Trump officials like Scott Bessent and Kevin Hassett had any integrity, they would have threatened to resign en masse as soon as the criminal investigation of Powell was revealed. But they don’t and they didn’t.

Paul Krugman is a Nobel Prize-winning economist and former professor at MIT and Princeton who now teaches at the City University of New York's Graduate Center. From 2000 to 2024, he wrote a column for The New York Times. Please consider subscribing to his Substack.

Reprinted with permission from Paul Krugman.