First Primary Could Shake Up The Race

By Mark Z. Barabak and Seema Mehta, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

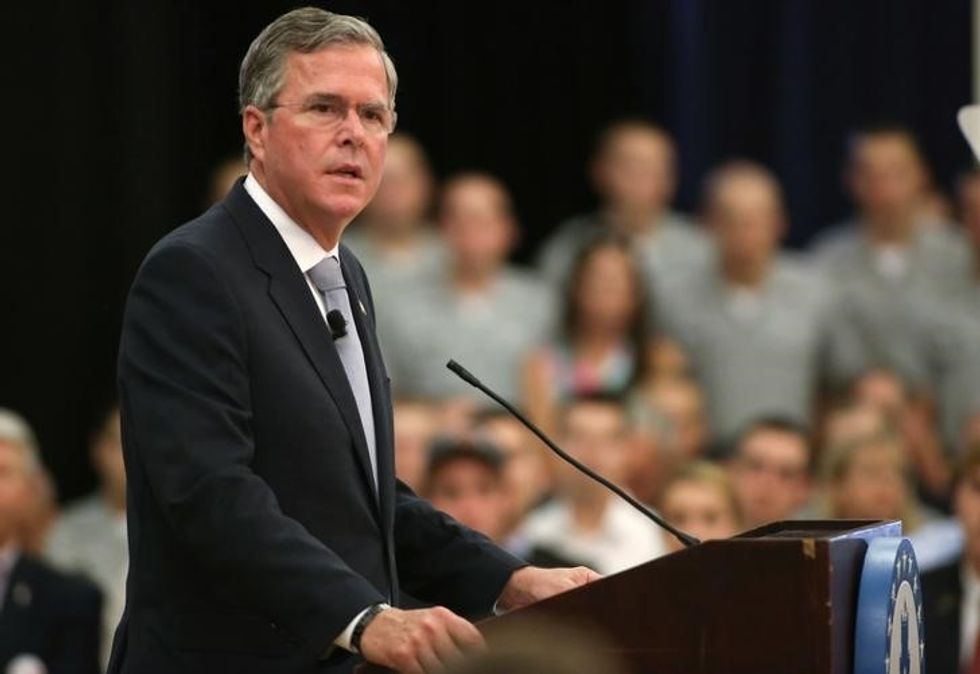

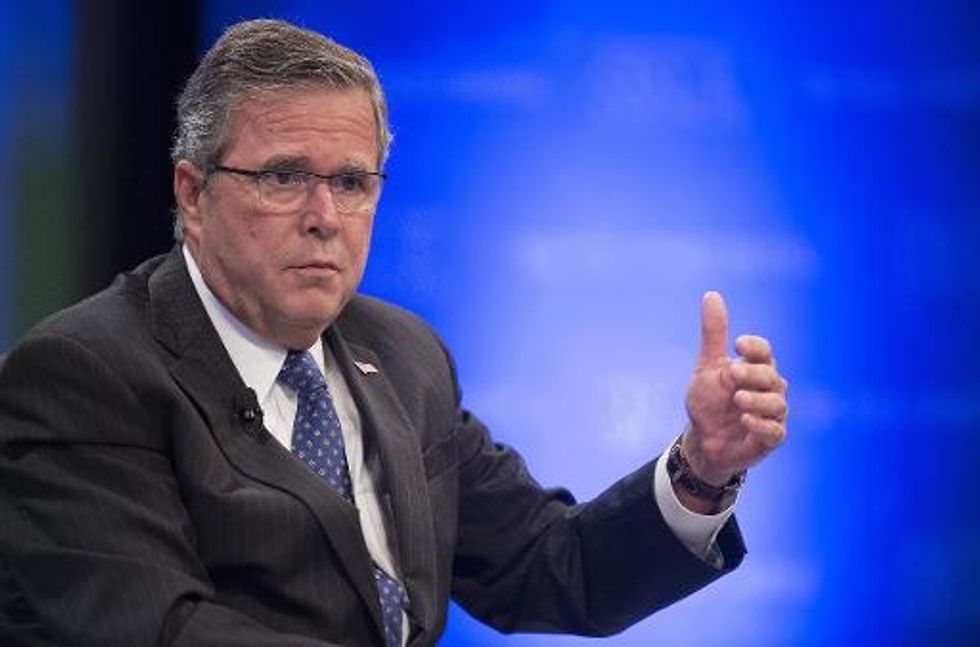

MANCHESTER, N.H. — When Jeb Bush paid a spring call on New Hampshire, hundreds of Republican faithful crowded the venerable “Politics & Eggs” breakfast for a glimpse of the dynastic candidate many thought would follow his father and older brother into the White House.

Earlier this month Bush returned, trailing far behind in polls, and the audience in the same speaker’s hall was less than a third the size. The reception was polite, but no one was leaping from the folding chairs.

The former Florida governor seemed unfazed.

The contest, he told reporters before his latest stop at St. Anselm College, “will look a lot different when we’re gathered back together after Christmas and when we’re gathered in the second, third week of January, the fourth week. … It always is different.”

Indeed, New Hampshire, which traditionally holds the first presidential primary, has a history of unpredictability, resurrecting candidates given up for dead, spurning front-runners or elevating also-rans with late-developing shifts in sentiment.

This time, the three contenders with the most to gain or lose are Bush, Ohio Gov. John Kasich and New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, who share the same essential political makeup. All three are pragmatically conservative problem-solvers running as the “serious” answer to the combustible — and, they suggest, unelectable — Donald Trump.

Their strategies are also virtually the same: Survive Iowa, which kicks off the nominating process with its Feb. 1 caucuses, then win New Hampshire eight days later — or at least run strongly enough to emerge as the alternative to Trump, Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas or whoever else stamps himself the favorite of social conservatives, who tend to rule the caucuses.

No candidate has spent more time and effort in the state than Christie, who was relegated to the Republican second-tier debate in November before a surge in New Hampshire polling placed him back on the main stage in December.

His roots in the Northeast help, as does his forceful persona at a time of renewed anxiety over terrorism. His endorsement by the Manchester Union Leader, the state’s largest and most influential newspaper, doesn’t hurt.

But more than that, Christie has been a virtuoso of the town hall meeting, a New Hampshire set piece that requires presidential hopefuls to take all comers until their questions, or the nighttime, is exhausted.

Christie, who used a boisterous series of town halls to promote his gubernatorial agenda — and build a national following — has held more than 50 of the open-ended sessions in New Hampshire. (Kasich has held more than three dozen.) An excerpt from one Christie appearance, where he delivered a passionate call for treating rather than punishing drug addicts, has been viewed on YouTube more than 8.5 million times.

“Some candidates can go shake every voter’s hand in New Hampshire and still lose miserably because they don’t have the ability to really connect with people,” said Drew Cline, the Union Leader’s former editorial page editor and a supporter of Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida. “There’s a certain bit of talent, charisma, charm that you have to have to make that kind of campaign pay off for you, and not everybody can pull that off.”

During his recent stop at St. Anselm College, it was Bush’s turn for the requisite grilling.

He sat at the front of a hall lined with photographs of candidates past, including his father, George H.W., mingling with supporters on the banks of a lake, and his brother, George W., smiling broadly at an outdoor rally.

For 40 minutes, the former governor answered every question he was asked: about immigration, terrorism, his Latin American studies in college, how he fends off fatigue on the campaign trail — a workout, including 100 sit-ups a day — and what historical figures or celebrity he would invite to the White House. “I wouldn’t invite Donald Trump,” he said dryly.

Afterward, he posed for photographs and shook hands with dozens of people who lined up.

Less than two months before the Feb. 9 contest, the Republican race seems unusually wide open, a fierce competition owing to the large field of serious candidates and the opening that Bush’s diminished status provides others on the center-right hoping to emerge as the GOP establishment favorite.

Polls show Trump leading in New Hampshire but averaging less than a third of the vote, followed at some distance by more than half a dozen others — Bush included — bunched closely together.

More significantly, the latest University of New Hampshire survey found fewer than 2 in 10 likely Republican primary voters had firmly decided whom to support.

(Barabak reported from San Francisco and Mehta from Goffstown and Manchester.)

©2015 Los Angeles Times. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Photo: Republican U.S. presidential candidate Jeb Bush speaks about his plans for the U.S. military at The Citadel, The Military College of South Carolina, in Charleston, South Carolina November 18, 2015. REUTERS/Joshua Drake