The IRS, Non-Profits, And The Challenge Of ‘Electoral Exceptionalism’

What the IRS scandal really shows us is that it’s getting harder and harder to draw a line between electioneering and political speech.

As the report of the IRS Inspector General shows, the agency’s scrutiny of conservative groups applying for non-profit status was, more than anything, a clumsy response to a task the IRS is ill-equipped to carry out – monitoring an accidental corner of campaign finance law, a corner that was relatively quiet until about 2010.

That corner is the 501(c)(4) tax-exempt organization, belonging to what are sometimes called “social welfare” groups, which enjoy the triple privilege of tax exemption (though not for their donors), freedom to engage in some limited election activity, and, unlike other political committees (PACs, SuperPACs, parties, etc.), freedom from any requirement to disclose information about donors or spending. The use of (c)(4)s as campaign vehicles didn’t originate with the Citizens United decision in 2010 (Citizens United, the organization that brought the case, was already a (c)(4)), but the decision seems to have created a sense that the rules had changed, and even small groups – especially, apparently, local Tea Party organizations — rushed to create (c)(4)s.

501(c)(4)s are not prohibited from engaging in political speech of most kinds. They are free to be “biased” without jeopardizing their tax exemption. They can advocate for or against legislation, they can lobby the government or criticize it. They don’t have to make any effort to be “non-partisan” – for example, they can support a proposal that is only supported by members of one party, or directly advise only members of one party. And they can engage in some activity directly intended to influence the outcome of an election, as long as that doesn’t constitute the organization’s primary purpose.

There’s some confusion about the definition of “primary purpose,” discussed in great depth elsewhere, but what the IRS was trying to do was to identify organizations that seemed more likely to be heavily involved in electoral activity. Since the organizations were new, there was no way to look at their actual activities to see whether they were mostly electoral. So the agency had to rely on clues in the applications, like names and telltale phrases. If organizations had words like “Democrat” or “Republican” in their titles, for example, it would be reasonable to look more closely at their election activities, or possible future activities, than an organization that called, for example, “Save the Turtles.” I’m told that organizations with the names of political parties do receive extra scrutiny, even if in some cases, like “Students for a Democratic Society,” the word might mean something unrelated to the name of the party. That’s what the closer scrutiny would find out.

“Tea Party” in 2009 and 2010 was unquestionably an election category – there were “Tea Party” candidates and there was a “Tea Party Caucus” in Congress. It was not unreasonable for the IRS to use that phrase as an indicator that an organization using that phrase might be more inclined to engage in elections. There are comparable phrases on the left – for example, the term “Netroots” might suggest election involvement, as there were groups that identified and endorsed “Netroots” Democratic candidates in 2006 and later. Perhaps there were simply fewer organizations applying for (c)(4) status with that word, or they came in before the 2010 flood, or perhaps the IRS did screen on that word – we don’t know.

While there’s a perfectly plausible case for the IRS to use flag-words that indicate an election-focused movement, the actual questions asked of the groups do raise some concerns. If accurate, they did seem to go beyond evidence that these organizations were primarily engaged in elections, such as questions about lobbying and the role of family members.

But the reason these questions are complicated for the IRS, or for any agency assigned to police these complicated distinctions, is this: The line between robust political speech and influencing elections has become frightfully difficult to draw. Finding the right line around what is an “election” is really the fundamental problem in campaign finance. Almost everyone accepts the premise of “electoral exceptionalism” – elections are structured and require some particular rules, different from the rules that apply generally to political speech. The rule in most states that keeps campaigners 75 or 100 feet from the voting booths is the most obvious uncontroversial restriction on political speech, and there is broad acceptance of the idea that direct contributions to candidates and campaigns should be limited to prevent corruption and dependence. But what happens after that? What about outside spending that looks just like campaign spending? We used to think there was a clear distinction between “issue ads” that were expressing a view on an issue and “electioneering communications” that were the equivalent of campaign contributions. That distinction is actually what the Citizens United case was about — the provision of the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act that defined broadcast communications that mentioned a candidate within 30 days before a primary or 60 days before a general election as electioneering, which had to be financed with regulated funds.

That was an improvised line then, and it’s gotten even blurrier since. Part of the problem is partisanship – it used to be, for example, that there were environmentalists in both parties, supporters of social spending in both parties. A political ad about the environment was just that. But what’s an ad or brochure attacking “Obamacare” during the election year? Every Republican opposes it, and they’ve given it the name of the president. The Tea Party was based on issues, yes, but above all else, it was based on unflagging, total opposition to Obama and congressional Democrats.

To figure out where election advocacy begins and regular political speech ends in these cases was certainly more than mid-level IRS bureaucrats in Cincinnati could handle. But it’s not an easy challenge for anyone. All the noise about IRS “targeting” and about free speech and corporate speech is a distraction from a real challenge of money in elections: finding an agreement on the line around an “election,” and establishing some clear rules for what happens within that line in order to ensure that elections are fair and open and don’t lead to corruption.

Mark Schmitt is a Senior Fellow at the Roosevelt Institute.

Cross-posted from the Roosevelt Institute’s Next New Deal Blog

The Roosevelt Institute is a non-profit organization devoted to carrying forward the legacy and values of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt.

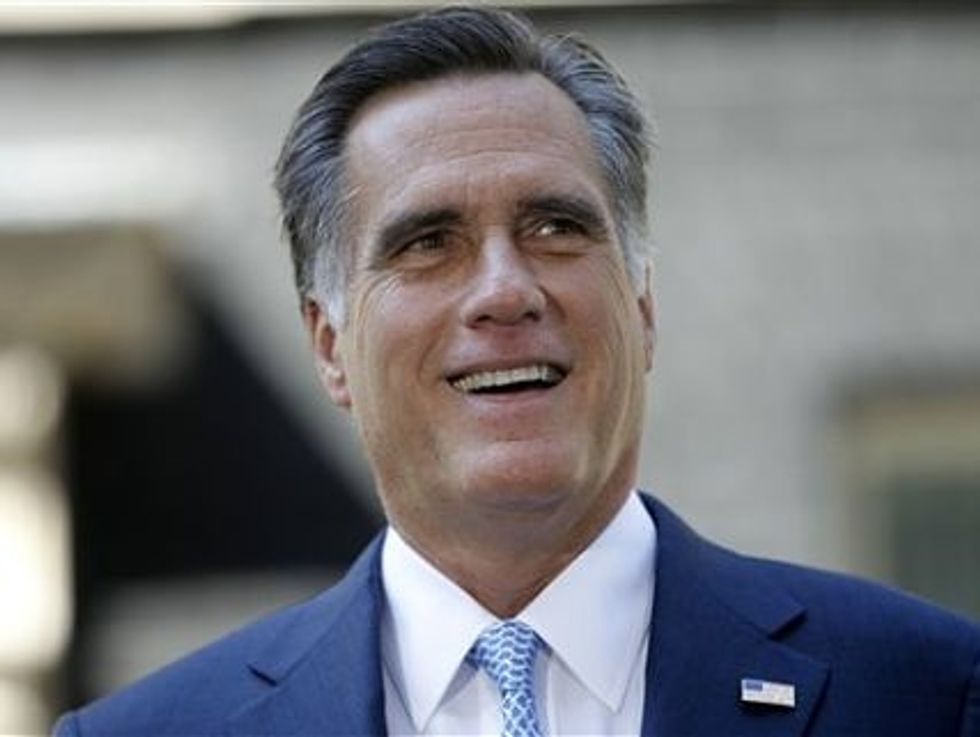

Photo: Matthew G. Bisanz via Wikimedia Commons