A New Data-Mining Technique To Uncover New Hampshire Influencers

By Sasha Issenberg, Bloomberg News (TNS)

In recent weeks, as Ben Carson began to slip in national polls of the Republican presidential primary field, volunteers at New Day for America, the super PAC backing Ohio Gov. John Kasich, began calling Carson backers in New Hampshire who might be open to Kasich as a second or third choice. But these weren’t just shots in the dark. They were equipped with a target list of voters identified as social anchors — people who are particularly influential within their personal networks, based on information culled from yearbooks, church lists, sports rosters, and other sources nationwide.

The list was prepared by Applecart, a New York-based data company that specializes in taking social-network analysis offline. Rather than merely looking for relationships validated on sites like Facebook and Twitter, Applecart is using a variety of sources to build its own map of the analog links between Americans. The idea is to help campaigns identify the voters who are likeliest to shape the attitudes and opinions of others around them, and then work to engage them as supporters. Applecart’s approach upends the logic of volunteer campaigns, in which campaigns look outward from the supporters they already have; instead, Applecart’s system starts with the targets they want to reach and then moves back to find people who are connected with them. “What we’re talking about is not finding that Rihanna is probably influential to my 19-year-old female cousin, but that the one person in her community whose name no one knows yet is influential (to her) because they went to high school together,” says Sacha Samotin, 24, one of Applecart’s founders.

Samotin and two classmates began the company three years ago as undergraduates at the University of Pennsylvania, meeting as research assistants to John DiIulio, a prominent political scientist who once served as adviser to George W. Bush. Under DiIulio’s guidance, the trio embarked on a project to take the sort of social-media targeting that was then in vogue — that year the Obama campaign developed a pioneering app called “Targeted Sharing” — and apply it to those who had not agreed to open up access to their online friend lists, or were not even active on Facebook at all. (A recent Pew analysis showed the generational cohort most likely to be Republicans was aged 69 to 86.)

Applecart executives are coy about its methods for retrieving the underlying data, although they hint that it stretches from labor-intensive work like library visits nationwide to scraping of websites, such as law-firm directories that inventory co-workers. Samotin says Applecart has developed processes around this work that it is currently seeking to patent.

On Applecart’s “social graph” of New Hampshire, each voter is treated as a node in a network with each of their known contacts webbed around them. (Around a dozen voters in the state were found to be “hermits,” with no meaningful interpersonal links.) Nuclear family, extended family, friends, professional acquaintances, and non-professional acquaintances are each assigned different statistical weights, then mixed with other values such as geographical proximity to calibrate a “connection score” between the voters in question. “A coworker who lives on the same block as a Manchester voter would be in a different category than a coworker who lives in Nashua,” says Samotin.

One application of such mapping was validated last year, when Applecart mimicked a classic 2006 experiment in which political scientists at Yale sent Michigan residents copies of their own voting records, along with those of their neighbors, with a threat to send out an updated notice after that year’s primary marking who had cast a ballot. Turnout among those who got the mailer increased 8 percentage points, the largest effect ever produced by a single piece of direct mail. When Applecart analysts replicated the experiment, they replaced neighbors’ vote histories with those whose names were likely to be personally familiar to the recipient. In one southern state that had competitive statewide elections last year, the “socially inspired” approach increased turnout among recipients by 14.6 percentage points.

An intimate approach to grass-roots politics is essential to Kasich, who has increasingly banked his campaign on a strong showing in a state where the difference between finishing in eighth place and third could be as few as 20,000 votes. Applecart was sought out by the pro-Kasich super PAC in part because — unlike outside groups backing Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio, and Ted Cruz — it wanted to develop the type of volunteer-based field activities that others have left to the candidates’ own organizations. “So many companies use data to overcomplicate politics,” says New Day chief strategist Matt David. “We’re trying to use data to leverage existing relationships to find Kasich supporters, and then turn them out.”

When volunteers arrive at New Day phone banks either in New Hampshire or Kasich’s political base of Columbus, Ohio, they are given call sheets prioritized by who the voters know. The targets are prospective “anchors,” those whom statistical models have identified as open to Kasich (even as a second or third choice) and also whose connection scores showed them as likely to be interacting with others. The idea is to convert these anchors into de facto campaign surrogates. “It doesn’t take too many people who are connected to a persuadable target to say nice things to them about John Kasich,” to start to close the deal, says Matt Kalmans, a 22-year-old co-founder of Applecart.

Outreach to party and elected officials, who are usually approached on a candidate’s behalf by other elites, follows a similar logic. “One of the strategies we’re using is instead of going directly to the (person from whom they’d like an endorsement) we go to the people around them and try to push them,” says New Day political director Dave Luketic. “That’s incredibly important because one of the metrics they use is: can this guy run a good campaign?” This is one area where the super- PAC is at a particular disadvantage, given that it is legally forbidden to directly communicate with the organization that secures endorsements. “We just set ’em up and the campaign knocks ’em down,” Luketic says.

©2015 Bloomberg. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

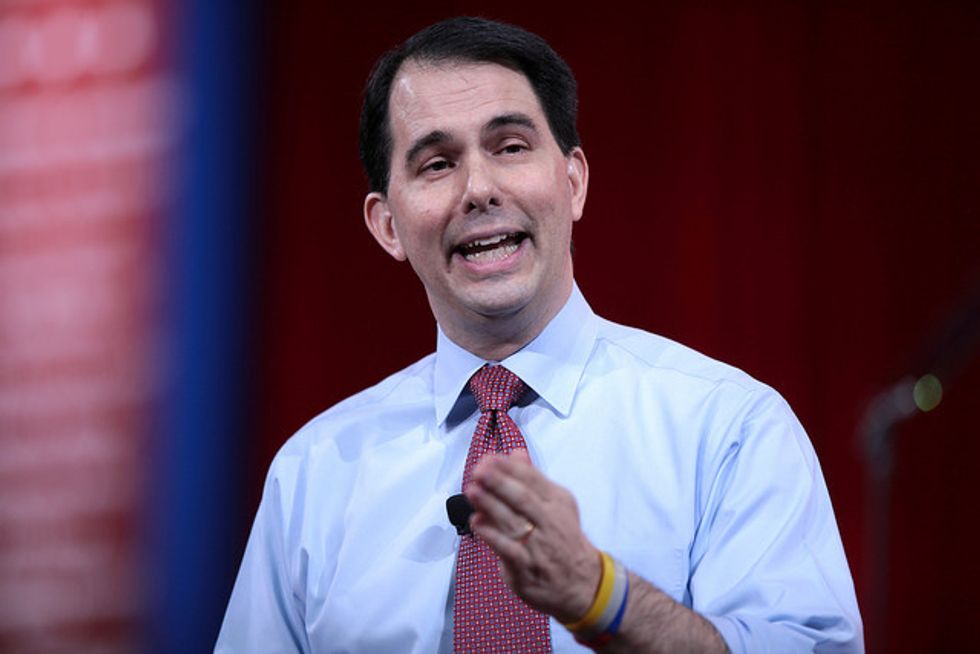

Photo: Republican U.S. presidential candidate Governor John Kasich speaks at the debate held by Fox Business Network for the top 2016 U.S. Republican presidential candidates debate in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, November 10, 2015. REUTERS/Darren Hauck