Kimmel's Triumph: A Sign That The Tide Is Turning Against Autocracy?

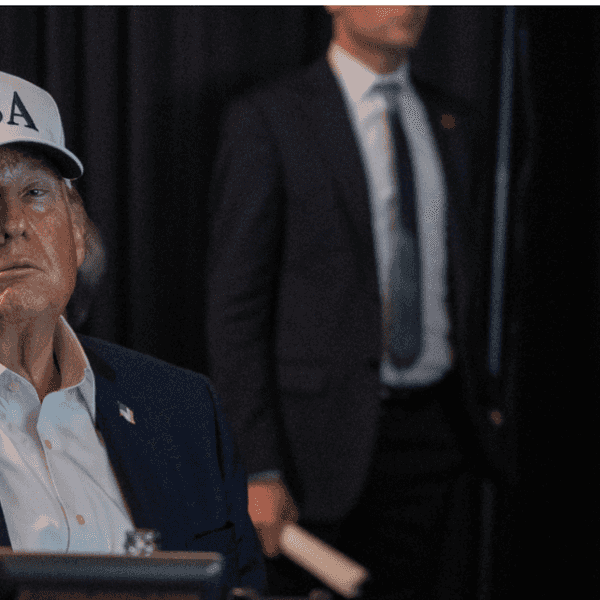

Hungarian President Viktor Orban and President Donald Trump at Mar-a-Lago on March 8, 2024

It’s irrefutable now: Trump is nakedly following the playbook of autocrats like Vladimir Putin and Viktor Orban. As his poll numbers fall, he is rushing to lock in permanent power by punishing his opponents and intimidating everyone else into submission. Craven congressional Republicans and a complicit Supreme Court have abetted Trump’s destruction of our democratic safeguards and norms.

Yet Trump has a significant problem that neither Putin nor Orban faced. When Putin and Orban were consolidating their autocratics, they were genuinely popular. They were perceived by the public as effective and competent leaders. Just nine months into his presidency, Trump, by contrast, is deeply unpopular. He is increasingly seen as chaotic and inept. As David Frum says, this means that he is in a race against time. Can he consolidate power before he loses his aura of inevitability? Will those who run major institutions – particularly corporate CEOs – understand that we are at a crucial juncture, and that by accommodating Trump they have more to lose than by standing up to him?

To put it bluntly, is the Jimmy Kimmel affair the harbinger of a failed Trumpian putsch?

Before I address that question, I want to offer some historical comparisons that illustrate how poorly Trump is doing compared with his role models, Putin and Orban. I wrote about this a couple of weeks ago, but I think the point deserves further elaboration.

First, Russia. Putin appears to have been extremely popular in the early 2000s, as he was consolidating power. His net approval — approval minus disapproval — was consistently above 50 percent.

Why was Putin so popular? Kitchen table issues. The Russian economy performed very badly for years after the fall of Communism, culminating in a devastating financial crisis in 1998. But Putin got to preside over a rapid economic recovery: Real GDP per capita doubled between 1998 and 2008:

Viktor Orban has never been as popular as Putin at his peak. Nonetheless, for most of the 2010s, as he consolidated power, his net approval was strongly positive, often by 10 points or more. Again, the main explanation was probably his perceived economic success. Orban took power at a time when Hungary’s economy was deeply depressed by austerity policies, and was able to preside over a large decline in unemployment:

Trump’s net approval, by contrast, turned negative within weeks after taking office and has just continued to fall:

As G. Elliott Morris points out, his position looks even worse when you consider intensity. Almost half the public disapproves “strongly,” twice the share with strong approval.

Some of the public’s disdain for Trump reflects alarm over his assault on democracy, the spectacle of abductions by masked secret police, his attacks on education and public health, his destruction of key agencies like the FBI, and more. Yet, as always, economics plays a key role in Trump’s cratering popularity.

People have not forgotten that Trump made big promises during the campaign: He would end inflation on day one, reduce the price of groceries, and cut electricity prices in half. None of that is remotely happening. Moreover, more economic pain is coming as the full inflationary impact of tariffs and deportations will soon be felt. Not surprisingly, consumer sentiment has plunged. It’s almost as low as it was in the summer of 2022, when Covid-induced supply-chain inflation was at its peak:

It’s clear that if Trump were subject to normal political constraints, obliged to follow the rule of law and accept election results, he would already be a political lame duck. His future influence and those of his minions would be greatly reduced by his unpopularity. But at this juncture he is a quasi-autocrat. He is the leader of a party that accommodates his every whim, backed by a corrupt Supreme Court prepared to validate whatever he does, no matter how clearly it violates the law.

As a result, Trump has been able to use the vast power of the federal government to deliver punishments and rewards in a completely unprecedented way. He has arbitrarily cut off funding to universities, refused to spend Congressionally-mandated funds, threatened to take away broadcast licenses, fired officials who are supposed to have job security, pardoned J6 insurrectionists, defied the lower courts, retaliated against those who have tried to hold him accountable, and enriched his family. This has created a climate of intimidation, with many institutions preemptively capitulating to Trump’s demands as if he already had total power.

But the fact is that Trump has not yet locked in his autocracy. Timid institutions are failing to understand not only how unpopular Trump is, but also how severe a backlash they are likely to face for surrendering without a fight.

They should understand, because some major corporations have already seen the costs of surrendering to Trump. Notably, Target’s decision to appease Trump by ending its commitment to DEI led to a large decline in sales and a falling stock price amid a rising market, and eventually cost the CEO his job. Law firms who have capitulated to Trump have lost clients and partners to law firms that stood up to him. And need we talk about the popularity of Tesla cars and Cybertrucks?

Yet Disney was evidently completely unprepared for the backlash caused by its decision to take Jimmy Kimmel off the air, a backlash so costly that the company reversed course after just five days — too late to avoid probably irreparable damage to its brand. And this time I hope and believe that other institutions will take notice.

It’s important to understand that Trump’s push to destroy democracy depends largely on creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. Behind closed doors, business leaders bemoan the destruction that Trump is wreaking on the economy. But they capitulate to his demands because they expect him to consolidate autocratic power — which, given his unpopularity, he can only do if businesses and other institutions continue to capitulate.

If this smoke-and-mirrors juggernaut starts to falter, the perception of inevitability will collapse and Trump’s autocracy putsch may very well fall apart.

So how can we make a Trump implosion more likely? The public can help by doing what Target’s customers and Disney’s audience did — make it clear that they will stop paying money to institutions that lend aid and comfort to the authoritarian project.

Like a schoolyard bully, Trump understands that effective intimidation relies upon picking off his opponents one-by-one. So institutions (such as law firms) can help by cooperating to resist Trump’s demands rather than simply looking out for their own interests. They should understand that there is no reward for appeasing MAGA with performative displays of cowardice.

And last but not least, Democrats should begin making it loud and clear that if and when MAGA is dethroned, those who broke the law, those who corrupted our democracy out of deference to Trump will be held accountable. For example, corporate mergers that hurt consumers but enriched Trump’s toadies can and will be re-examined by future Democratic administrations.

It’s ironic, but thanks in part to a late-night comedian, it’s becoming clear that America is not yet lost.

Paul Krugman is a Nobel Prize-winning economist and former professor at MIT and Princeton who now teaches at the City University of New York's Graduate Center. From 2000 to 2024, he wrote a column for The New York Times. Please consider subscribing to his Substack.

Reprinted with permission from Paul Krugman.

- 'Release The Tapes': Lawmakers Demand Details On Homan Bribery Probe ›

- 'Galling Cowardice': ABC Cancels Kimmel Under Trump White House Pressure ›