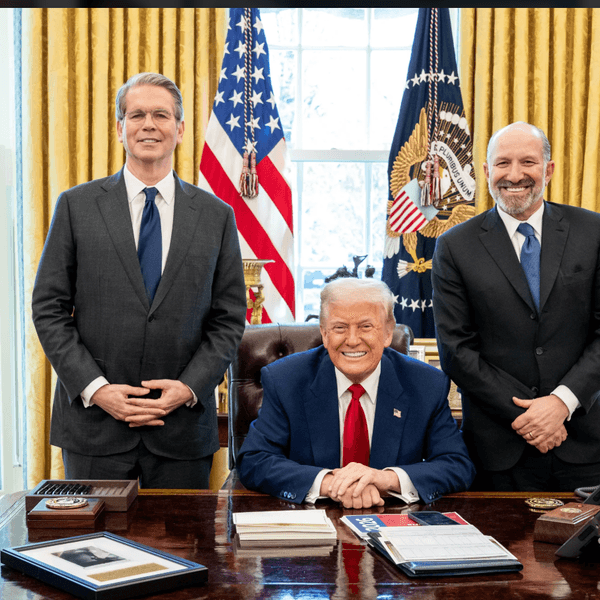

Justice Brett Kavanaugh

The consensus after Wednesday’s much-anticipated argument in Trump v. Cook was that the Supreme Court of the United States was likely to rebuff the president’s attempt to fire Federal Reserve governor Lisa Cook.

But while the bottom line was relatively clear, the rest of the story was murkier. The justices expressed frustration with the underdeveloped record in the case and with their obligation to figure out how to proceed on a record that was, in many ways, preliminary.

Thus, Justice Samuel Alito asked why the Court was being asked to proceed in such a hurry, noting concerns that key parts of the factual record were not clearly before the justices.

Of course, “hurried” here is five months since the attempted discharge, but that’s lickety-split in the world of appellate litigation. More to the point, the preliminary nature of the case and the record are completely a function of the Court’s own decision, as it has done so frequently in Trump’s first year, to grant review of the case in the early stages on an emergency-posture basis.

That posture virtually guaranteed an underdeveloped record. For example, the justices had no pre-termination hearing to assess, and the actual “notice” of her firing was a Truth Social post by Trump announcing her discharge, before any formal process had run its course.

The justices were left to wrestle with two broad approaches. The first would be to send the case back to the lower court for factual development. That would get the case out of the Court’s hair, but it would leave the underlying substantive issue unresolved and might require further Court consideration down the line. The second would be to bite the bullet and offer some minimal definition of “cause,” and then determine that Trump’s proffered reasons for firing Cook did not meet that standard.

For example, the Court could conclude that cause under the statute cannot rest on alleged gross negligence alone. Or that it cannot be based on pre-appointment conduct, as it was here. Or that it cannot be grounded in conduct unrelated to the officer’s professional duties.

But there was an additional, largely unspoken problem hovering over the entire oral argument.

That problem is that the president is a lying liar who wakes up lying and lies all day (LLWWULALAD).

The solicitor general was forced to play along with the fiction. His chief argument was a vigorous defense of the idea that Cook should be discharged because of her supposed gross sin: an inaccurate statement on mortgage paperwork.

Cook’s lawyer, the masterful Paul Clement, argued that the administration’s proposed definition of cause amounted to an at-will standard in disguise, green-lighting any reason the president chose to fasten onto.

And more to the point, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, the functional center of the Court and its most frequent member of the majority last term, pushed the parties to docs on “real-world, downstream effects.” Kavanaugh posed the spectre of “what goes around, comes around,” meaning that a future Democratic administration could discharge Trump appointees en masse under the expansive cause standard the administration was championing.

That hypothetical rests on an important assumption: presidential good faith. If that assumption holds, the danger Kavanaugh described largely evaporates. A truthful president would not invoke threadbare allegations of minor or remote misconduct—such as a disputed entry on a mortgage application predating a governor’s tenure—to justify removal.

The concern animating Kavanaugh’s questions, however, is that a president might use a nominal “cause” as a make-weight excuse for what everyone agrees would be improper: the dismissal of a Federal Reserve governor for policy disagreements.

But for that concern, a weak but bona fide discharge for cause wouldn’t be a big problem. Kavanaugh, a veteran of Washington’s embroiled political battles (recall his service for Ken Starr in the Clinton investigation, which he cited in his pugnacious confirmation testimony) understands that the actual risk is a weak cause standard could easily be met and serve as a pretext for policy differences.

And of course, that is precisely what happened here. Nobody in Washington believes that Trump actually cares about Cook’s long-ago mortgage paperwork. The problem is not merely that the cause is weak; it is that the asserted cause is an obvious pretext.

And this is one of only dozens of instances in which Trump is doing a similar move of citing some sonorous concern—mortgage fraud, or academic integrity, or false statements to Congress—that is really a shield for raw political will.

And that’s because Trump is a LLWWULALAD.

So whatever rope the justices give him—even to fire someone for weak cause—would in practice amount to letting him bully the Fed to do his bidding, including on the setting of interest rates, in other words, doing exactly what his lawyer agrees would be unlawful but getting away with it by lying about the true case.

The markets would clearly understand that. The result would be a collapse of confidence long anchored in the Fed’s professionalism.

But only where the president is a LLWWULALAD.

At one point, Kavanaugh asked Sauer directly whether the Court was supposed to second-guess the President’s stated reason or whether, instead, it should “defer and assume the stated cause was valid.” Sauer responded by invoking the Court’s longstanding tradition of not questioning the good faith of the executive.

And you can be fairly well assured that the justices will not retreat from that doctrine, which will be at issue in future cases involving Trump, in particular, given that he is a LLWWULALAD. If the Court applies an irrebuttable presumption of good faith to Trump’s determinations—about, for example, the existence of an insurrection, a rebellion, or other emergency conditions—it risks green-lighting extraordinary powers that could be used in many ways, including to try to reverse an election.

Here, however, the justices have already carved out the Federal Reserve from the administration’s broader wrecking-ball effort to eliminate for-cause protections across independent agencies. So it was common ground in the argument that the Fed’s for-cause protection is constitutional and governs Cook’s case.

That should take us a long way toward Cook’s reinstatement. Ordinarily, it would be enough. But the Court must still confront the problem that the president is a LLWWULALAD.

The Court knows the score, as did everyone in the courtroom. Expect the justices to find a way to rebuff Trump without saying out loud what they all know to be true.

They will not say it, but they understand that allowing Trump to prevail on an obvious pretext—a lie—would mean that, in Dickens’s words, the law is an ass.

When the opinion issues, it should not take much deciphering of the Court’s decorous prose to understand that there is an ass in this case—but it is not the law.

Harry Litman is a former United States Attorney and the executive producer and host of the Talking Feds podcast. He has taught law at UCLA, Berkeley, and Georgetown and served as a deputy assistant attorney general in the Clinton Administration. Please consider subscribing to Talking Feds on Substack.

Reprinted with permission from Talking Feds.

- Irredeemable Justice: Letitia James' Indictment Tolls The Depth Of Corruption ›

- Newsom Trolls Trump (And Red States) With True Crime Statistics ›