Virginia's First Female Governor Inaugurates Her 'Affordability Agenda'

Abigail Spanberger, inaugurated on January 17 as the 75th governor of Virginia, began to implement her agenda centered around her campaign pledges to make the state more affordable, improve education, and address gun violence almost immediately after taking office.

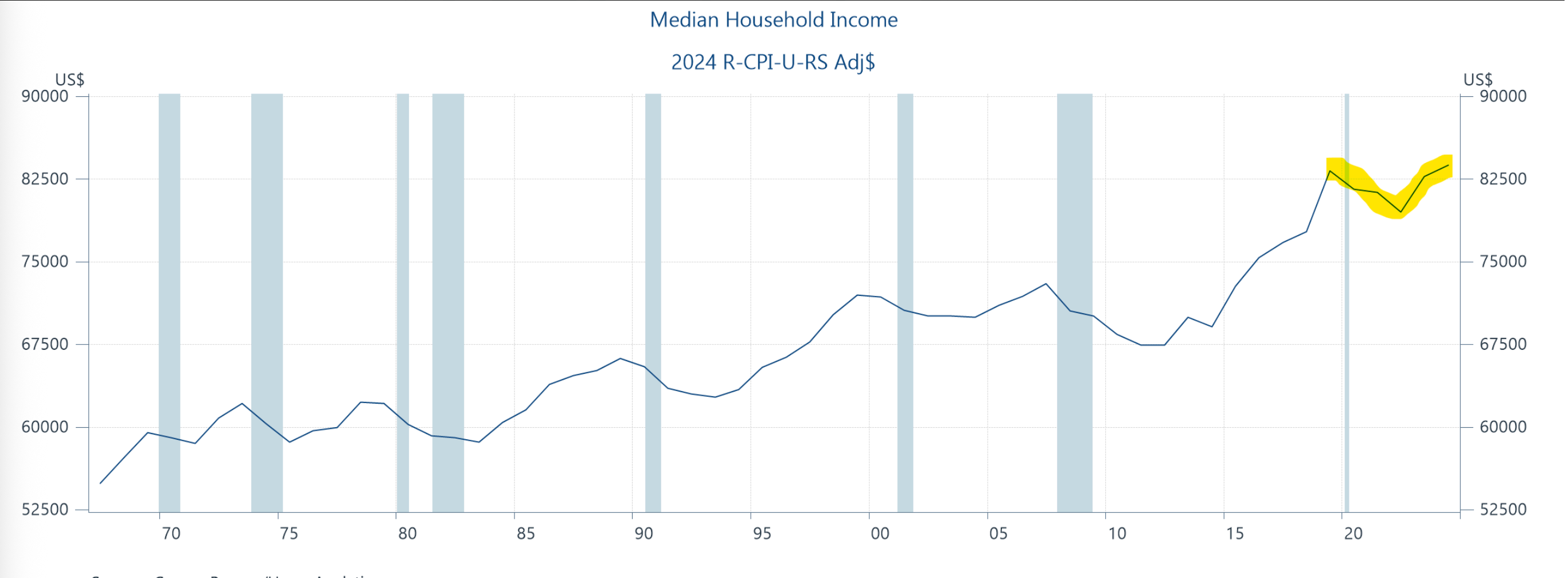

Minutes after taking her oath of office, Spanberger signed 10 executive orders. The first order, called the Statewide Affordability Directive, ordered all Cabinet secretaries and executive branch heads to report to her within the next 90 days “identifying immediate, actionable budgetary, regulatory, or policy changes that would reduce costs for Virginians” addressing cost savings in housing, health care, energy, education, child care, and living expenses.

Other orders created an Interagency Health Financing Task Force to strengthen Virginia’s health care system, ordered a multi-agency Housing Development Regulation Review to increase the supply of housing, directed the Department of Education to strengthen literacy, math, school accountability, and assessment in the commonwealth’s public education systems.

“Today, we are responding to the moment. We are setting the tone for what Virginians can expect over the next four years: pragmatic leadership focused on lowering costs and delivering results,” Spanberger said in a press release. “My administration is getting to work on Day One to address the top-of-mind challenges facing families by lowering costs for Virginians in every community, building a stronger economy for every worker, and making sure that every student in the Commonwealth receives a high-quality education that sets them up for success. These executive orders represent the first steps in our work to create a stronger, safer, and — critically — more affordable future for our Commonwealth.”

On the campaign trail, she promised to address rising housing, health care, and energy costs and touted an eight-page plan detailing how she would do so.

Spanberger laid out her policy agenda in an address to the General Assembly on January 19, which is centered around the Affordable Virginia Agenda she and Democratic leaders in the House of Delegates and Senate are proposing in order to lower those costs.

Among her proposals was legislation to limit the profits of pharmacy benefit managers, provide targeted assistance to Virginians at risk of losing health insurance coverage due to the expiration of federal subsidies, boost energy storage, help Virginians make their homes more energy efficient, help renters avoid eviction, and build more affordable housing.

“These are not hyperpartisan proposals; they are commonsense solutions,” Spanberger told lawmakers. “And I believe they deserve support from every member of this body, Democrats and Republicans.”

Spanberger urged legislators to create a statewide paid family and medical leave program, increase subsidized child care, raise the hourly minimum wage to $15, and increase pay for teachers. She promised to sign bills, vetoed last year by then-Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin, aimed at curbing gun violence, such as a ban on ghost guns, a law blocking convicted domestic abusers from accessing firearms, and an expansion of Virginia’s red-flag law temporarily disarming those judged to be an imminent danger to themselves or others.

Finally, Spanberger expressed her support for three constitutional amendments to be voted on by Virginians in November that would guarantee reproductive rights, automatically restore the right to vote for individuals convicted of a felony after they have completed their sentences, and codify the rights of two adults to marry.

She defended a fourth proposed constitutional amendment to temporarily change the way Virginia draws its congressional maps, likely to be considered by voters in April, saying: “Virginia’s proposed redistricting amendment is a response to what we’re seeing in other states that have taken extreme measures to undermine democratic norms. This approach is short-term, highly targeted, and completely dependent on what other states decide to do themselves.”

Giving the Republican response, Republican state Sen. Glenn Sturtevant criticized Democrats for advancing the redistricting amendment, saying it would not lower costs, according to a Cardinal News transcript. “We also need to be honest about what Democrats are proposing, because it will make life more expensive,” Sturtevant said, “Their tax-and-spend agenda would cost Virginia families billions each year, adding thousands of dollars in new burdens for the typical household.”

Reprinted with permission from the Virginia Independent

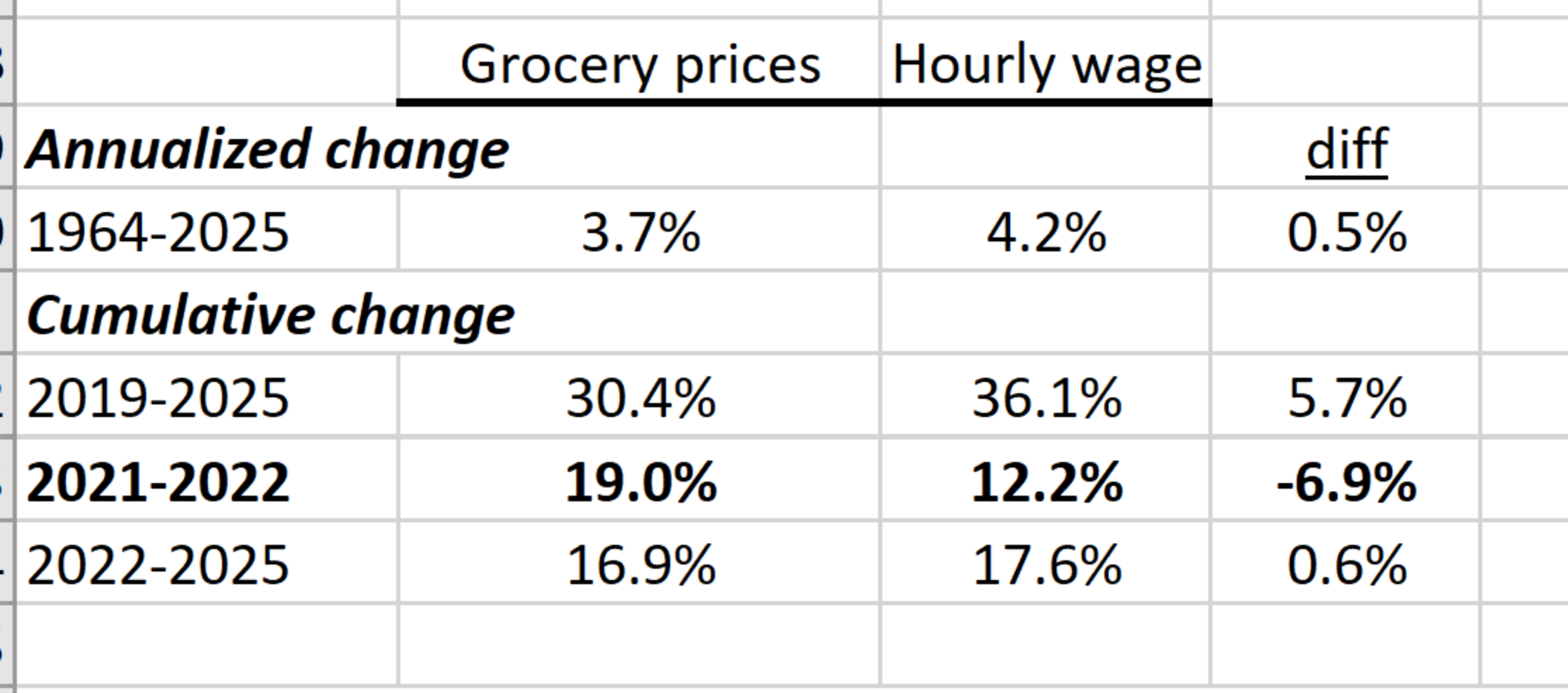

Bureau of Labor Statistics data through August 2025, wages for production non-supervisory workers

Bureau of Labor Statistics data through August 2025, wages for production non-supervisory workers