As readers know, I yield to none when it comes to elevating the affordability crisis, along with the policy and politics therein. But in most of my work in this space, I at least tip my hat to the fact that it’s not just about P (prices). It’s about Y/P (where “Y” is income, so Y/P is inflation-adjusted, or real, incomes). By which I mean, affordability is not just about prices. It’s also about how far your paycheck goes, given how much things cost.

As Neale Mahoney and I wrote a bit ago:

Another way in which economists historically think about affordability is in terms of the real purchasing power of paychecks and incomes. That is, we are more prone to think about incomes relative to prices (Y/P) than prices in isolation. This makes good economic sense as an equal percentage increase in prices and incomes has no impact on affordability in real terms.

We go on to point out, however, that this…

…is not how most people tend to internalize the problem. As recent research by Stefanie Stantcheva has shown, people tend to credit themselves for wage or income gains but believe price increases are imposed on them by outside forces. This means that even when a price increase is matched by a wage gain, people end up feeling worse off.

I’m acutely aware of how much price levels—what things cost—have been a core source of economic angst for a good while now, which is why I’ve been devoting most of my policy time working with folks to craft affordability policies.

But that said, I’ve lately been seeing affordability takes that go too far for my comfort in leaving off the income part of the equation. A typical example shows a price of a good or service on the affordability docket, like groceries, going up over time, and declaring that therein lies the problem.

That’s a mistake on numerous levels. Progressives, especially in periods of rising inequality, have long argued that workers’ paychecks should grow closer to the rate of productivity, which is a fancy way of saying that the bakers, not just the bakery owners, ought to get a fair slice of the pie they’re baking. But, of course, as the Economic Policy Institute has long shown, that’s not always been the case (though contrary to claims that inequality only goes up, there are periods, often during full employment labor markets, wherein median compensation growth kept pace with productivity).

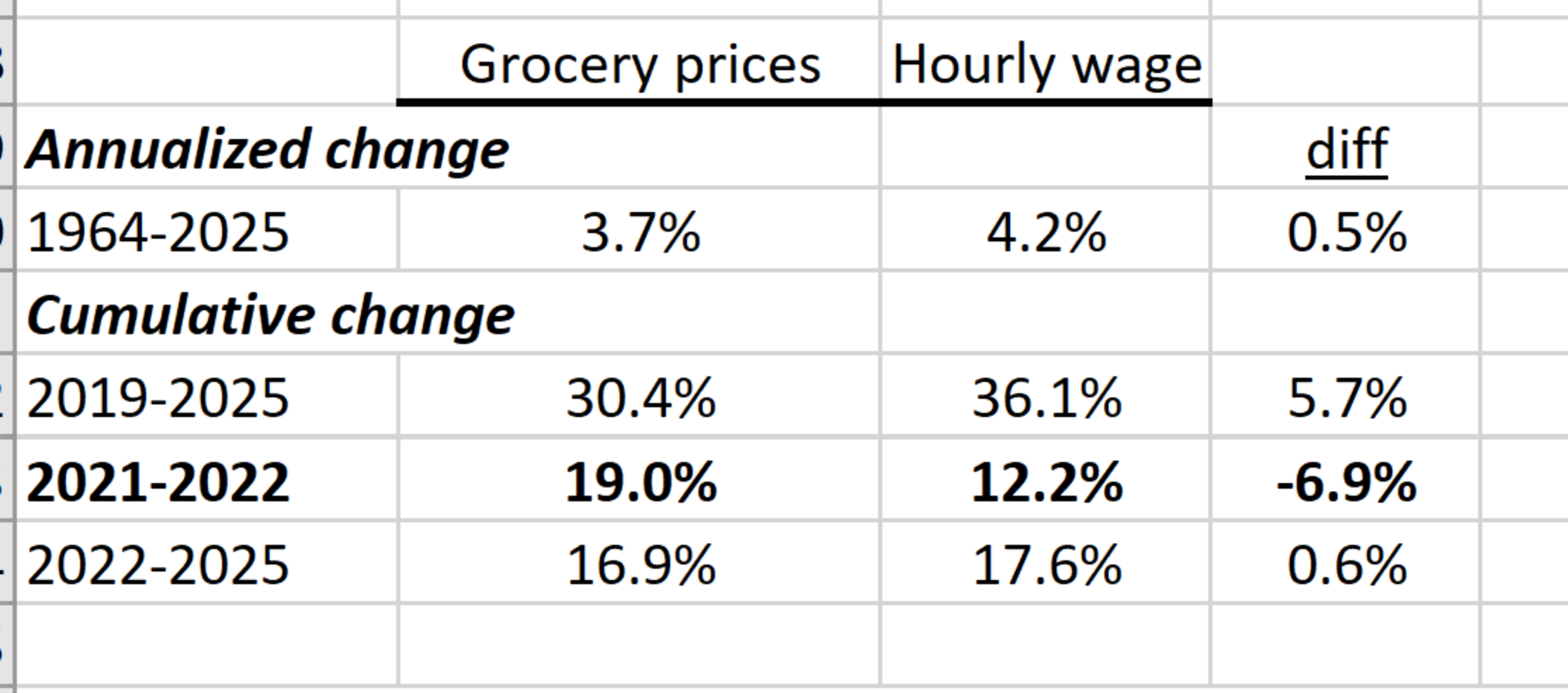

The table below provides a useful microcosm of this story by tracking the growth in both hourly wages and groceries over various time periods. Over the long-term, since the mid-1960s, annualized wage growth has outpaced grocery-price growth by a half-a-percent per year. Cumulatively since 2019, grocery prices are up by almost a third, which is a lot for this series, but wage growth is up almost six percent more since then.

However, the ‘21-’22 period, when inflation spiked in general and groceries in particular, wage growth lagged well behind. Though affordability issues had loomed large well before this shock, it was this sudden, huge jump in the price level—and again, not just groceries, but gas too, especially post-Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—that unleased the affordability crisis that remains predominant today.

How that crisis eventually dissipates must be some combination of these events: prices fall back to where they used to be, incomes growth outpaces price growth, effective affordability policies take hold, and time passes. Falling prices are very unlikely and, because it would take a huge, negative economic shock—think deep recession—to get there, not desirable (of course, removing the tariffs would definitely help for specific goods). I suspect if you asked the average person would you rather egg prices go back to where they were if it meant losing your job, they wouldn’t take the deal.

Policy work can help too, but a) not until competent policymakers are in power, and b) policymaking and implementation take time. And speaking of time, its passage is a critical piece of the puzzle. You don’t see me walking around enraged that gas is no longer $0.60/gallon, which it was when I started driving. In fact, the combination of low inflation, income growth beating that low inflation, and time passage is a reliable recipe for affordability, though, as noted, structurally unaffordable sectors like child care, health care, and housing must be addressed and ameliorated by policy.

I mentioned income growth above, so before we close, let’s look at that. Because hourly wages are the fundamental building block of working-family incomes, they were the focus of the grocery table above. But affordability at the household level is a function of n*h*w/p, were n is the number of people in the household who are working in the paid labor market, h is their average annual hours of work, and w/p is their average real hourly wage (and that’s just market incomes; non-market incomes, like tax credits, unemployment benefits, etc., also matter).

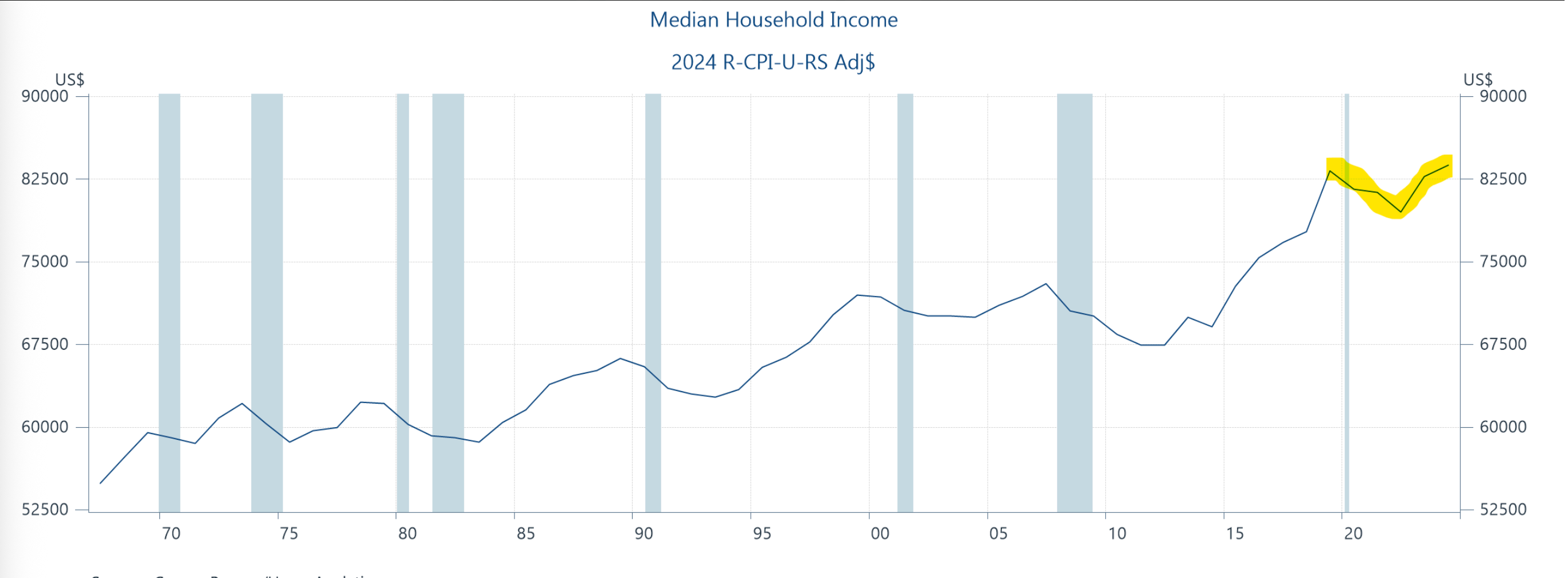

Here’s real median household income. Because of n and h in the formula above, it’s somewhat cyclical. In this regard, solid research reveals that tight labor markets help boost the bargaining clout of middle and lower-wage workers, boosting n, h, and w/p. But if you eyeball the end of the figure, you see the pandemic and the inflationary spike that followed led to sharply falling household incomes. From 2019-22, nominal income grew eight percent which isn’t bad, but inflation grew 13 percent, with the difference, -five percent, being the rate at which real income fell. That too is a source of the current affordability crisis.

But doesn’t the figure show household income jumping back up, and doing so with a slope that’s as steep as any other in the picture? Yes, it does, and that’s a key ingredient of the recipe above, driven by lower inflation, the strong job market, and solid real wage gains that for awhile there were stronger at the bottom of the pay scale than at the top. But you’ll also note that the recent gains just take the real income level back to where it was pre-pandemic, and that too feeds the affordability crisis.

Bottom line, while prices are understandably a current obsession, and the Stantcheva point above regarding the psychology of these dynamics is also in the mix, we must not ignore or downplay the importance of the earnings, incomes, wealth. They are just as important to affordability as prices, and the gap between real pay and productivity—i.e., wage inequality—is an historical factor that has played a key role not just in how people feel about economic fairness, but in how they vote about it.

Jared Bernstein is a former chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers under President Joe Biden. He is a senior fellow at the Council on Budget and Policy Priorities. Please consider subscribing to his Substack.

Reprinted with permission from Econjared.

\

- Democrats Must Address Looming Cost Spike In Private Health Insurance ›

- When Scott Bessent Claims Trump Is Making Life Affordable, Who Believes Him? ›

- As Insurance Costs Surge, GOP No Longer Pretends To Support ... ›

- Republicans Push Skimpy, Unaffordable Health Coverage As Costs Keep Rising ›

- After The Blue Wave, Affordability Trumps Tariffs At The MAGA White House ›

- Fox News Spinning Madly To Make Sense Of Trump's 'Affordability' Message ›

- 'No No No No!" Treasury Secretary Roasted For Denying Inflation Under Trump - National Memo ›

- $20 Trillion Investment? Searching For Trump's Imaginary Economic Boom - National Memo ›

- With Looming Implosion, Health Care Reform Could Dominate 2026 Elections - National Memo ›

- Virginia's First Female Governor Inaugurates Her 'Affordability Agenda' - National Memo ›