This week, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi just flouted an order of the Catholic Church by receiving communion from a priest in Vatican City. Last month, the archbishop of the San Francisco Archdiocese put Pelosi on the “do not serve” list when he informed her that “should [she] not publicly repudiate [her] advocacy for abortion ‘rights’” he would declare that she cannot partake in the sacrament of Holy Communion.

Since then, other bishops have voiced their support for that decision. "The church clearly teaches that abortion is a grave evil, and that public advocacy for — and support of — abortion is, objectively speaking, such a manifest grave sin," Portland, Oregon Archbishop Alexander Sample posted on Facebook.

It’s not a new issue. A South Carolina parish priest denied then-candidate Joseph Biden the Eucharist in 2019 because of his pro-choice position during his presidential campaign. Last year, a conference of Bishops deliberated making it official church policy to keep him from Communion. They ultimately didn’t enact the ban.

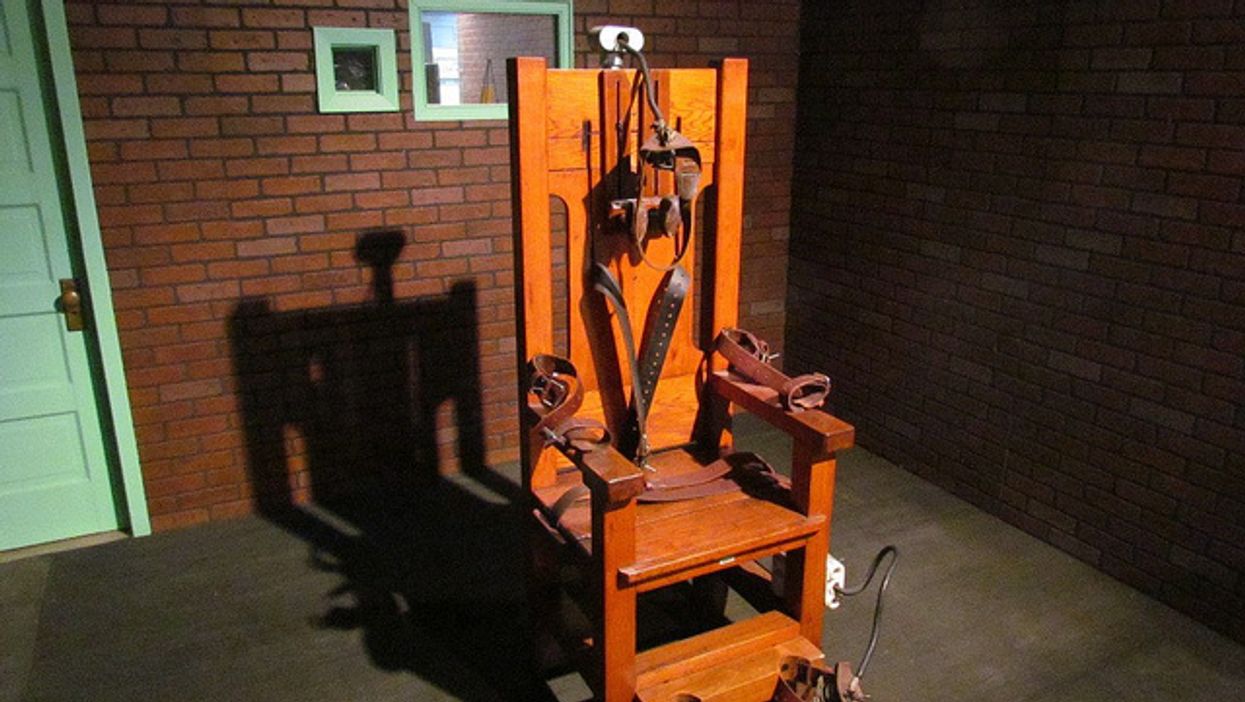

Even to debate whether President Biden, Speaker Pelosi or any other pro-choice person should receive communion in the Catholic Church while doing nothing to hold Catholic jurists and lawyers accountable for violating other church teachings is enough for me to consider leaving the faith. To wit, no churches have announced that they would withhold the sacrament from Supreme Court Justices who have approved the death penalty, as recently as last week.

When I was incarcerated from 2007 to 2014, I rediscovered my Catholic faith and started attending the weekly masses held on Saturday mornings in the chairs assembled in the prison school hallway. It’s not that I am so pious or good; someone sentenced to years in prison can’t survive without belief in things unseen.

Of course I leaned on the fact that faith supports my redemption — the Bible codifies my visiting rights. But the entire time I was there, the same Church that sustained me would have allowed — indeed, even supported — the state’s taking of the lives of two women who lived in my housing unit. Former nurse Chasity West barely escaped a death sentence for a capital murder conviction and Irish authorities refused to extradite former attorney Beth Ann Carpenter unless the State of Connecticut promised not to pursue such a penalty.

Now they’re both serving life without parole, also known as LWOP, which Pope Francis has condemned.

It was only after I had been home for almost 4 years that the Vatican announced a revision to the official Catechism of the Catholic Church in August 2018. The death penalty, it said, was “an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person” and “inadmissible” in all cases.

Yet, approximately one year after the change in the Catechism, then-Attorney General William P. Barr — and former board member at the Catholic Information Center, an Opus Dei-affiliated bookstore and chapel — resurrected the federal death penalty and oversaw the Justice Department that put 13 people to death. One of them was the first woman to be killed by the federal government, altogether more than had been executed in the previous 56 years combined.

Yet no priest or archbishop called for yanking the wafer from his mouth.

Nor has anyone removed Justices Samuel Alito, Amy Coney Barrett, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh or Clarence Thomas from the communion lines at their Beltway churches.

Since the Catholic Church changed its position in 2018, the Supreme Court has involved itself in a total of 44 capital punishment cases (24 in the 2018-19 term, 14 in the 2019-20 term, 0 in the 2020-21 term, 6 in the 2021-22 term) over four separate court terms. Of those 44, only two decisions ended up protecting the life of the prisoner: the 2019 decision in Flowers v. Mississippi and the 2020 opinion in Sharp v. Murphy. Notably, Catholic justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch dissented in the Flowers case and Justices Alito and Thomas dissented in the Sharp decision.

Many Supreme Court decisions turn on very specific legal questions, and deciding those issues often seems to have nothing to do with the punishment at the end of the case. That’s what happened with the case of Nance v. Ward, decided last week. It was actually the more conservative justices who dissented in approving execution by firing squad. At issue was the legal proceeding that a condemned man could use to challenge his method of execution. But it bears mentioning that in their dissents, the Catholic justices approved of a method of execution — lethal injection — that would likely amount to cruel and unusual punishment for Nance, who has compromised veins.

I can’t say whether writing a judicial opinion is different from active advocacy, which is what the bishops complain of in their communion bans. The actions of Catholic Supreme Court justices may not count as advocacy, but they do amount to complicity. Gorsuch recused himself from a capital case before the country’s highest court, not on the basis of the subject matter; but because he had been involved in the lower courts’ decisions. For the most part, the justices engaged with these cases. They touched them. Their fingerprints remain on the death warrants.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett wrote article about this very issue in the Marquette Law Review in 2008, arguing that if a judge’s moral conviction would have prevented her from imposing the death penalty, then she needs to recuse herself from a case involving capital punishment. Coney Barrett noted the difference between being the judge who imposed the sentence and an appellate judge who is once removed from the penalty, but she didn’t follow her own advice. She failed to recuse herself in the case of Orlando Hall, a man convicted of the rape and murder of the sister of rival drug dealers, but instead noted a dissent to allowing Hall’s execution to proceed.

Conspicuously, though, Coney Barrett didn’t dissent in dismissing a stay order based on the fact that Hall, who is Black, was convicted by an all-white jury. And, just last month, she joined the majority opinion in Shinn v. Ramirez in deciding that potentially innocent men sentenced to die shouldn’t have a chance to prove that their post-conviction attorneys didn’t provide them with adequate representation. The Court’s decision in Shinn v. Ramirez is the least Christian attitude anyone can take toward someone who’s challenging a criminal conviction.

The prohibition on abortion is about 120 years older than the Catechism rule so perhaps it’s an issue of marination in the idea for bishops and judges. But the difference in attitudes toward abortion and death penalty is obvious: one life isn’t culpable, at least not yet. That’s why, before 2018, church leaders operated in “virtually unanimous agreement” that “civil authority, as guardian of the public good, has been given by God the right to inflict punishments on evildoers, including the punishment of death.”

I was baptized as an infant so I never chose the Church. The reason why I came back and stayed is that the Catholic Church is the temple of do-overs. God doesn’t want sacrifice; he wants mercy. And the church’s disparate treatment of reproductive rights supporters and death penalty proponents doesn’t square with that core value.

A healthcare provider can reevaluate their actions and behave differently; they often get a second chance to bring a child to term. Those who carry out death sentences have no such opportunity, unless they prevent the next execution — and not one Catholic with the power to do so was brave or responsible enough to take that stand.

Pelosi and other lawmakers have supported the now-overturned Roe v. Wade precedent out of a moral conviction that women deserve to be protected. It’s a position my God would allow and permit her to participate in the sacrament.

I understand that rules are rules. If public support for abortion services disqualifies someone from receiving communion, then I need to step out of line myself and join the lawmakers sidelined by bishops.

But if rules are rules, then Catholic bishops should impose similar bans on Justices Alito, Coney Barrett, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Thomas. That would be equal treatment under church law.

Chandra Bozelko did time in a maximum-security facility in Connecticut. While inside she became the first incarcerated person with a regular byline in a publication outside of the facility. Her “Prison Diaries" column ran in The New Haven Independent, and she later established a blog under the same name that earned several professional awards. Her columns now appear regularly in The National Memo.