If You Want Us To Help Prove Your Innocence, Start With This Checklist

The year 2022 closed out with many readers reaching out to me with cases that they think deserve more scrutiny. I’m flattered and I would like to help. But, on occasion, the outreach I receive is a little light on foundational documents.

I’m kicking off 2023 with a guide that anyone can use if they’re looking for help on a criminal case from a journalist or trying to help a prisoner reduce their sentence.

This is what you should do before and while seeking any journalist's assistance on a criminal case or post-conviction challenge.

Come correct: Collect all your information before reaching out: docket numbers, copies of court files (never walk out of court with original records; that’s a crime), lawyers’ names and all of their contact information (physical and email addresses as well as office telephone numbers and cell phone numbers).

All correspondence between the defendant/prisoner and lawyers can illuminate what happened. An inmate file would be helpful if the person is incarcerated. A signed release of information allowing attorneys to speak with the reporter should be handed over up front. It can accelerate our research.

Write a timeline: As Tennessee Senator Howard Baker asked former White House Counsel John Dean about Watergate: “What did the president know, and when did he know it?”

Often it’s the order of events that matters in these cases because it either confirms or challenges what people know. This is key. Without a linear depiction of what happened and when, it’s hard to see who knew what and when. Because criminal cases aren’t just about actions but also the accused persons’ state of mind, seeing the events spatially can be essential to any inquiry.

Get transcripts: Transcripts are tricky to take to a reporter because technically they’re not public records; court reporters/monitors own them privately. Their private nature makes them costly. Courts can grant fee waivers for transcripts to applicants who qualify (an incarcerated person, friends and family members with limited means). The clerk in the courthouse where the hearing or trial was held can provide these forms; they vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

Courts won’t approve these fee waivers for journalists and news outlets. We have to pay for these volumes and it’s an expensive gambit if they don’t reveal much to assist with the investigation.

The effort of applying for the waiver and having master copies of testimony is worth it. Sometimes you might wonder if the judges who write appellate opinions even read the transcripts at all when you see the way the testimony (the content of the transcripts) appears in a court’s opinion. Those inconsistencies provide fertile ground for someone other than a lawyer to find a reversible error.

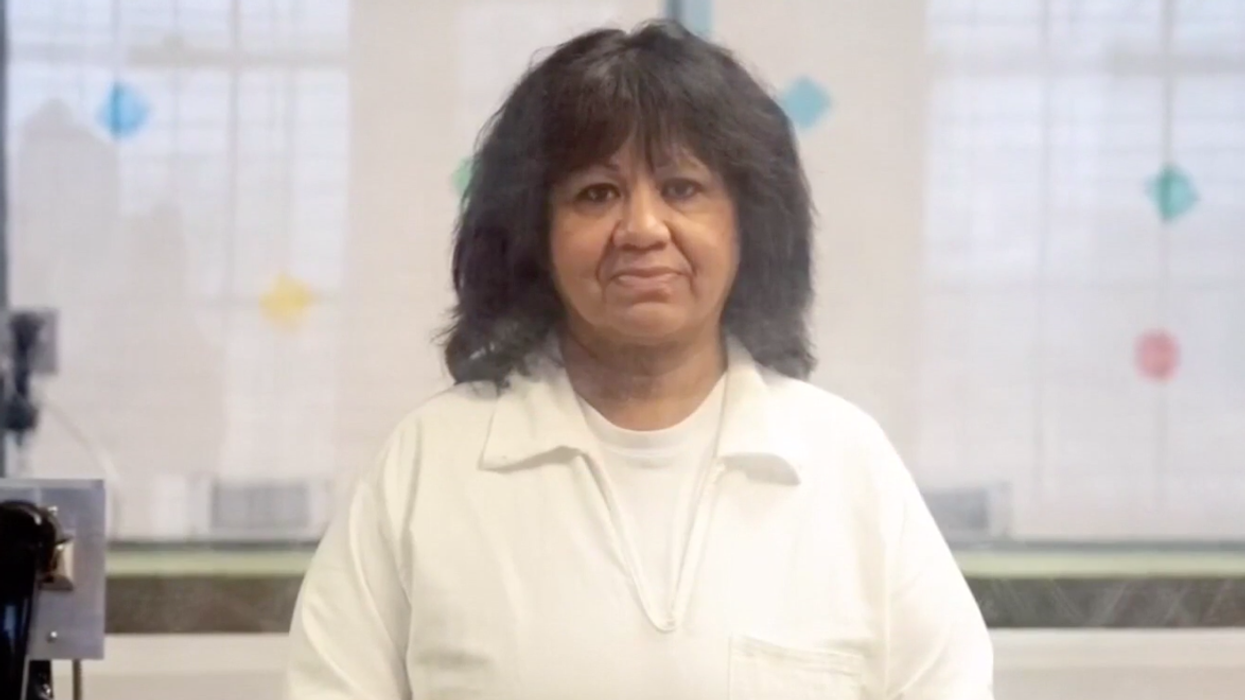

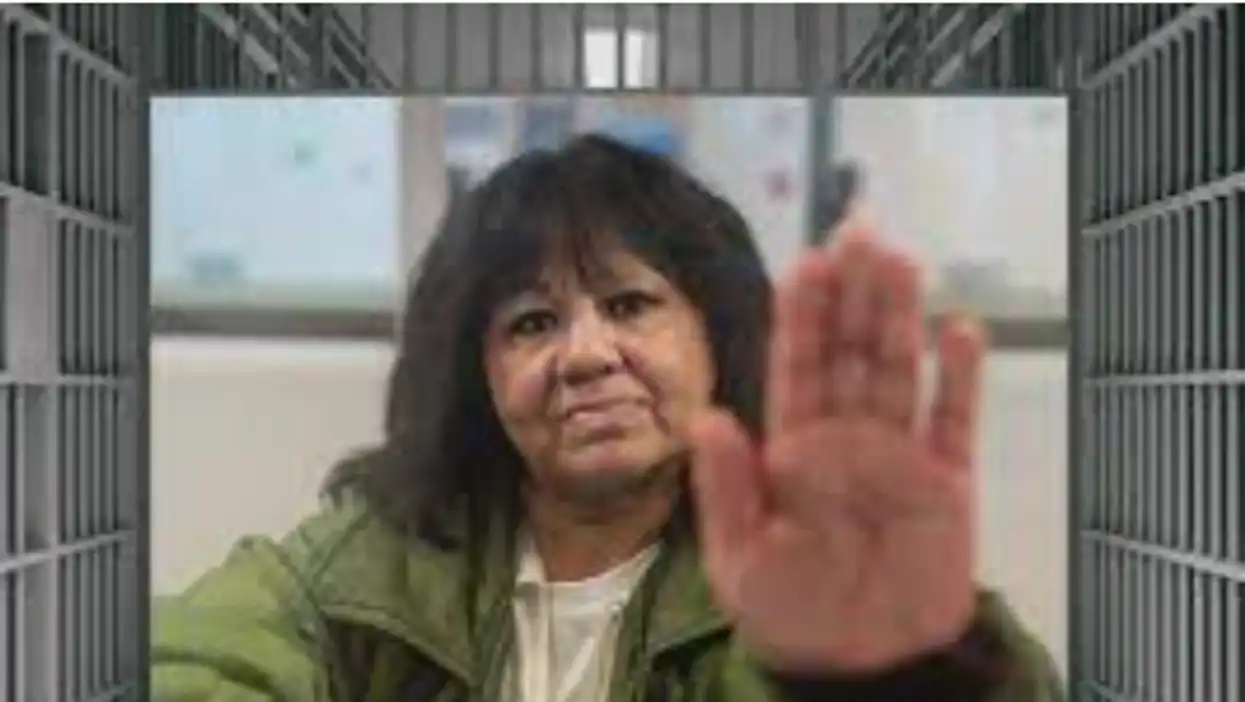

We did exactly that here at The National Memo in 2022; we found false evidence in the trial transcripts of Melissa Lucio, the only Hispanic woman sentenced to death in Texas. Her execution was paused pending a hearing after her attorneys included our reporting in a petition to the court. Read the Lucio series here.

Keep a copy: Do this for all paperwork you complete, like fee waiver applications you file, rejections to requests for records.

Sometimes agencies don’t cooperate and it may seem impossible to get the documents you need. But that may be part of the story and we’ll need that proof.

Don’t be offended when a journalist doesn't take your word for it: When we ask for confirmation of a part of the story, it’s not because we suspect you of misrepresenting anything. We need confirmation for our editors.

If there’s no other evidence besides your knowledge of a particular situation, then turn that knowledge into evidence. It can be done relatively easily. In that case, use this template to make out an affidavit. An affidavit — sworn, out-of-court testimony — can be used as evidence. It doesn’t prove that the facts within are true, but it does show the witness’ willingness to expose themselves to perjury charges if the contents of the statement are proven false. Often journalists can use these statements in their reporting.

Find a therapist: This isn’t a layperson diagnosis of mental illness. I’m not pointing out flaws in those people seeking justice for friends, family members or even prisoners. It’s quite the opposite.

Wrongful convictions, lengthy incarceration, waiting for a languid bureaucracy to fix mistakes they made in a millisecond are traumatic experiences even for bystanders. Trying to explain the facts and the trauma to a journalist wastes time and asks them to act as an advisor of sorts. We know — and especially I know — how harmful injustice is, not just to the defendant or inmate, but also people close to them.

But explaining to us how stressful all of this doesn't help anyone — we’re supposed to be investigating — but it’s also pointless because we’re not trained to assist in those ways. Finding a professional with whom you can work out your feelings will enhance your ability to secure attention — and therefore assistance for your cause. Find A Therapist is just one source of information on service providers in your area.

Be Patient: Getting new records or finding the best witness can take time. It won’t happen overnight.

Be Realistic: While pressure from the press can break logjams and even expose innocence, it’s not always possible. We’d love to clear some names and spring some bodies from custody but we’re not magicians.

Chandra Bozelko did time in a maximum-security facility in Connecticut. While inside she became the first incarcerated person with a regular byline in a publication outside of the facility. Her “Prison Diaries" column ran in The New Haven Independent, and she later established a blog under the same name that earned several professional awards. Her columns now appear regularly in The National Memo.