It was only in the last 24 hours before the Brexit vote that it began to hit home just how massive, and maybe insane, it would be if the United Kingdom decided to leave the European Union.

The result was in doubt, not least because of the relatively large and growing numbers of undecided voters in those last few days. It is clear now where most of those undecided voters decided to go.

The results are in. The UK, or at least England and Wales, has decided decisively it no longer wants to be part of a huge, free market, free trade, free travel bloc.

A great deal of the international debate and analysis centered on the economic impact of leaving: On the UK, on other European countries, on the “market”, even on the United States. Rampant confusion has reigned.

But there are other elements to consider: nationalism, borders, sovereignty, and the question of whether the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland may even crack under the strain of leaving.

The debate, in England at least, was simply put. Those on the Leave side believed the country can stand alone, make its own, better deals on trade, and stay financially afloat.

And leaving will help keep those bloody immigrants out with nice, sturdy border controls, they said. They won’t even need a Trumpian wall; no-one has yet suggested, at least publicly, building one along what will be the country’s only land border with the EU, in Ireland.

Those on the Remain side believed this would be a complete disaster, including financially (they were right), while many were appalled at the idea of going it alone with such a large rump of jingoistic, nationalistic, anti-immigrant fellow countrymen and women.

But it is a fact that many feel betrayed at how the European Union has developed, and not just the Conservative Eurosceptics, or nasty far right nationalists. And not just in the UK, but across the EU.

This vote will encourage many others across the continent, both those of that often dark nationalist, deeply anti-immigrant, bent, but also those that believe there is a super elite running and rigging the game, caught in the thrall of the financial markets. Think a Trump-Sanders ticket: This is an anti-establishment vote, and nothing is more establishment, in the minds of Leave voters, than Brussels.

There is a real feeling among voters that countries have truly suborned much of their sovereignty, and much of their decision making, to Brussels, and that decisions are largely being made not by the European Parliament, but by the entirely unelected European Commission, and the European Central Bank, seen as the water carrier for the big European financial institutions.

Take Ireland, where the ECB, and particularly its former chairman, Jean-Claude Trichet, are reviled by many in the country.

In essence, taxpayers in the country were saddled with billions in extra debt after the Irish government — which had bailed out the country’s banks — was bullied and threatened into not burning bondholders. And the bondholders deserved to be burned, as many of them were big European financial institutions which had lent recklessly to Irish banks, allowing them in turn to carry out a manic lending spree of truly epic proportions.

Austerity, and lots of misery, followed. Then Trichet gave the metaphorical finger to a banking inquiry set up to look at the mess, by refusing to attend and answer its questions.

It is only one example, and Ireland will never exit the EU, minus a complete break up, but Europe is a deeply unhappy family.

Yet it is incredibly hard to believe that the UK will now leave it altogether, not least because the consequences are unknown — financially, on trade, on its citizens not being able to travel freely through the EU, and on the country itself.

A tradesman in Boston, East Midlands — which posted a 75 percent Leave vote, the highest in the country — will find out somewhere down the line that his work options severely limited. He just voted to not be able to work freely in 27 other countries. He arguably voted against his own interests.

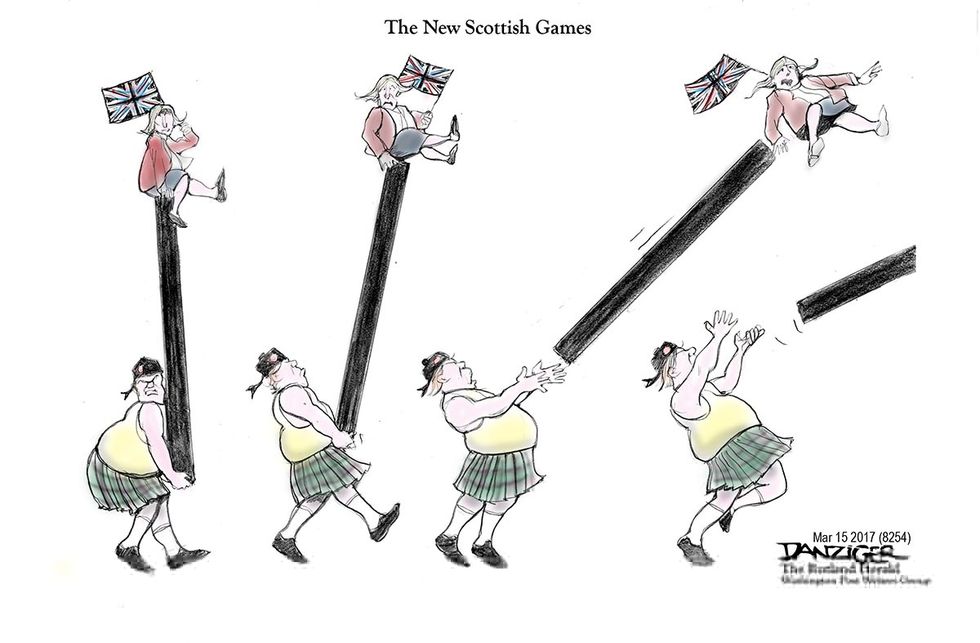

Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland’s SNP First Minister, who urged Scots to vote Remain, which they did with a large majority, has made clear her party will pursue independence. Further, she suggested that if Scotland became independent the party would enter “decisions and discussions” to join the Euro.

And then there is Northern Ireland, where it has been somewhat strange to follow what was an incredibly muted debate. It voted to remain, but not by a large majority. It and the Republic of Ireland are so meshed together now — through trade, travel, and otherwise — there will be consequences to this vote.

In the end, this was an English row. And it was England, with its Welsh appendage, that voted to leave, decisively.

Photo: A British flag flutters in front of a window in London, Britain, June 24, 2016 after Britain voted to leave the European Union in the EU BREXIT referendum. REUTERS/Reinhard Krause