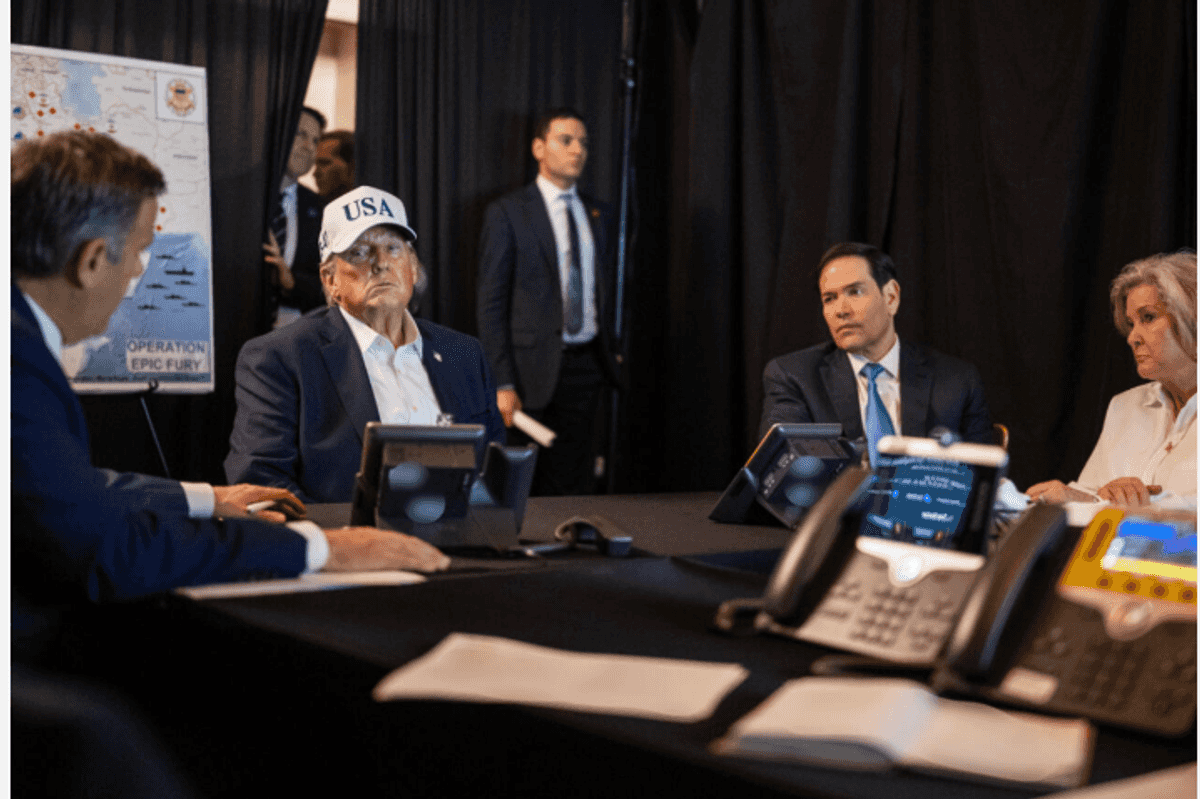

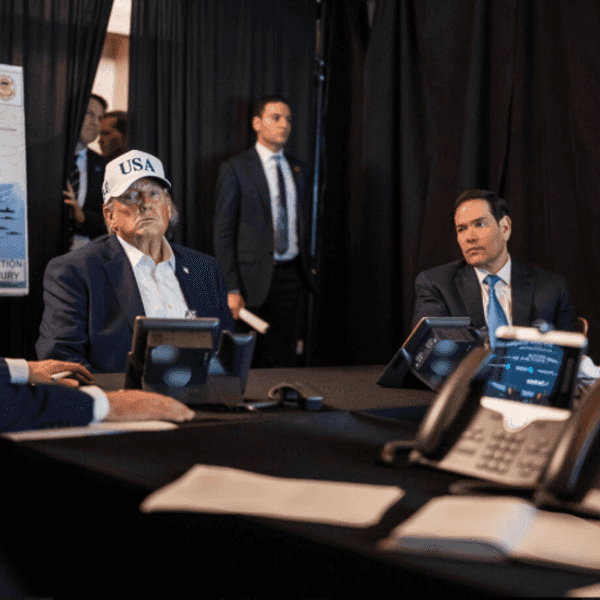

President Trump with Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Chief of Staff Susie Wiles in White House Situation Room

President Trump unilaterally decided to take the nation into war. Congressional Republicans not only failed to undertake what is arguably their most critical role in making this decision. They voted down a war powers resolution to “curb President Donald Trump’s powers in the Iran war…”

It’s the second vote in as many days, after the Senate defeated a similar measure. Lawmakers are confronting the sudden reality of representing wary Americans in wartime and all that entails — with lives lost, dollars spent and alliances tested by a president’s unilateral decision to go to war with Iran.

There has never been a war this unpopular with the American people at this early stage. “About half of registered voters — 53% — oppose U.S. military action against Iran, according to a new Quinnipiac Poll conducted over the weekend. Only 4 in 10 support it, and about 1 in 10 are uncertain.”

It’s of course not the case that Americans are sympathetic to the oppressive Iranian theocracy. Far from it. It’s that the case for war was never made to them. If it’s “regime change” then this appears to have demonstrably failed, as the new leader is as hardline as the last one. If it’s “protecting the Iranian people” who disdain the regime, then that surely requires “boots on the ground” versus an air campaign that’s killed hundreds of innocents.

With no rationale, Americans are faced with two economic challenges: the impact of the war on energy costs, which speaks directly to their affordability concerns, and the cost of the war, both in human and fiscal terms. That is, other than MAGAs who can comfort themselves with “if Trump’s doing it, I’m for it,” the rest of the country is weighing the action on a scale with costs on one side and rationale on the other. But there’s zero on that side of scale.

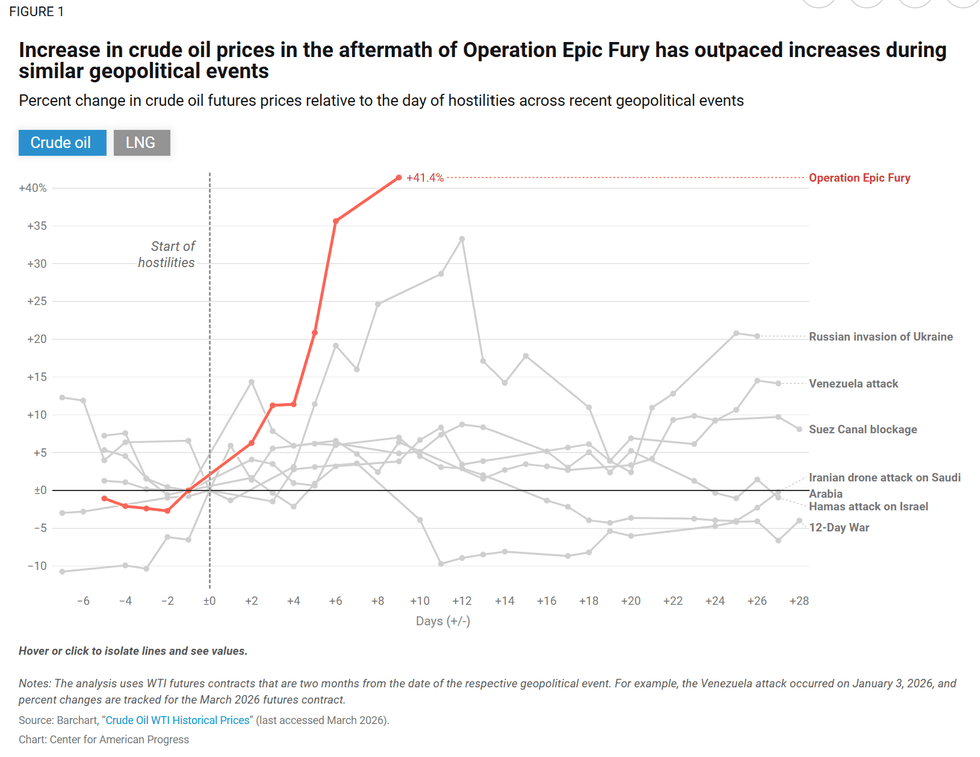

On the costs side of the scale, however, the evidence is stark. The figure below shows how fast the oil price has gone up relative to past conflicts. Go to the doc and you can click on the same figure for natural gas, which is also shut in due to the war and its impact on shipping through the Strait of Hormuz.

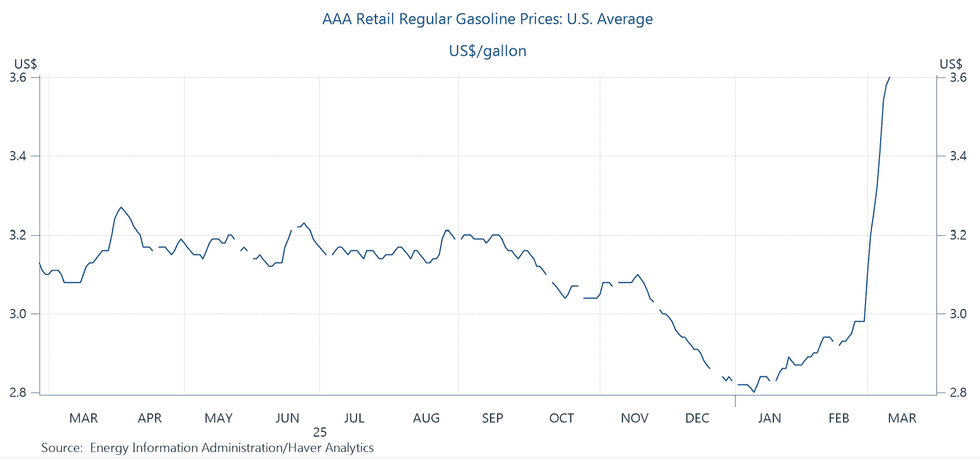

Here's the gas price:

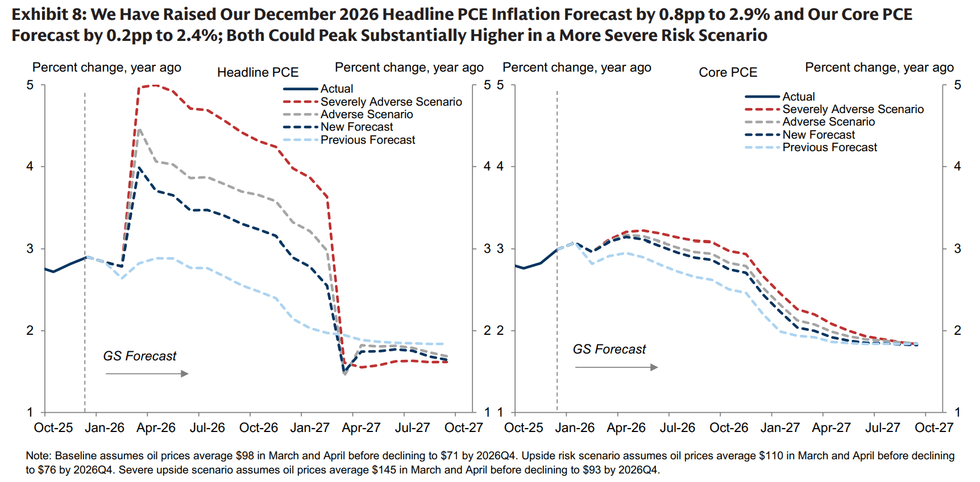

And here’s a new GS Research take on inflation and growth impacts given different duration/adversity scenarios (because core inflation excludes energy and food costs, we see less impact there; as long as you don’t need to eat or go anywhere, you’re good!):

Take a beat and eyeball that figure on the left. Then consider the main, economic stressor facing American families right now, i.e., affordability. Then imagine undertaking a war, with no clear rationale (I know I keep saying that, but it’s crucial—Americans will rally if we understand the need to go there), that is likely to send headline inflation a point higher (their “new forecast”) and could, under the most adverse scenario, send it to five percent.

Their real GDP forecast tracks how higher prices ding growth, though note that none of these forecasts, including the most severe, are recessionary.

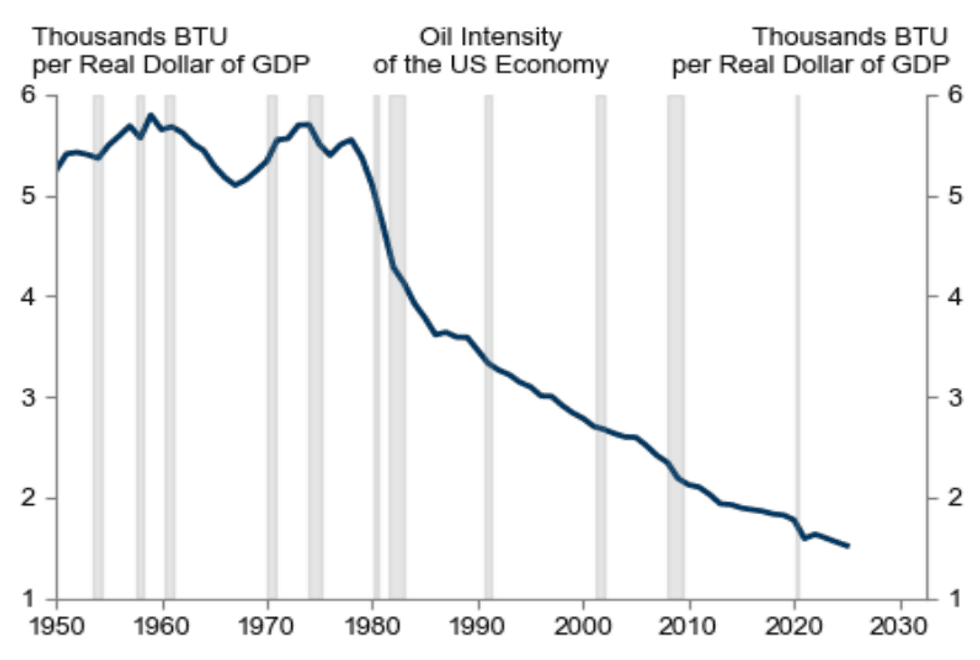

We’re just a lot less exposed, in a macro sense, than we use to be to oil shocks. Our trade exposure to the Strait is <5% (percent of our trade flows) and our oil intensity (how much oil we use to generate a dollar of real output) is way down.

That’s good news, of course, but for years now we’ve seen the disconnect between macro and micro, between solid GDP growth and low unemployment and people’s economic experience. And we know that has a lot to do with how far their paychecks are going. I’ve touted real wage growth as recently as yesterday in my write-up of the CPI report, but higher war-induced inflation will cut into that buying power.

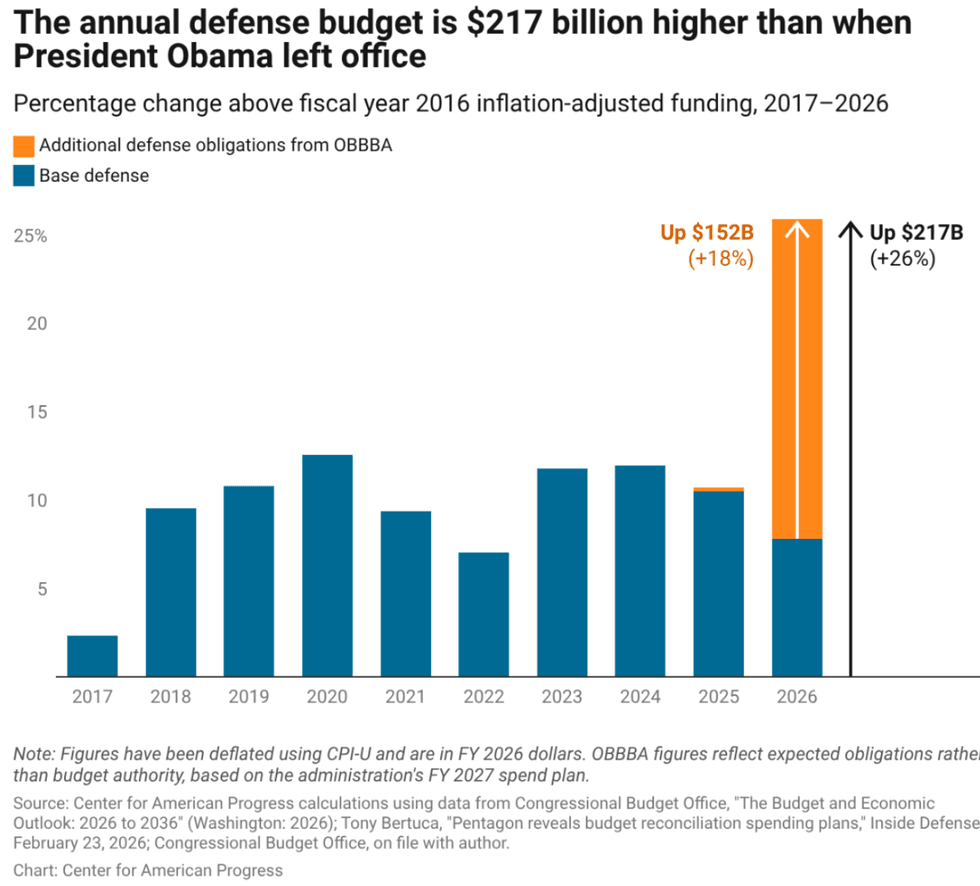

Then there’s the fiscal and human costs, both that of our servicemen and women and the victims caught in the crossfire of the air campaign. I urge you to read this powerful memo to Congress from Bobby Kogan and Damian Murphy from the Center for American Progress. Regarding the likely forthcoming request to Congress for more money (I’m hearing $50 billion) to prosecute the war, they write:

While the Trump administration has not yet presented its supplemental request, the White House will likely request funds to replenish stockpiles for which it already has sufficient funding through a mixture OBBBA (an enormous amount of which still remains unobligated) and through its general transfer authority inside the annual defense budget. In other words, the White House seems poised to request more money for weapons for which they already have tens of billions of unused dollars.

Kogan and Murphy also remind us that the Defense Department’s budget “keeps growing without increased accountability (in December, the Pentagon failed its eighth financial audit in a row).” The very least Congress can do is not authorize even more resources for this benighted, unilateral adventurism that’s already hitting Americans in their wallets.

There are just wars, cases where our nation has intervened in ways that have been far more costly to life and treasure than that in any of the figures shown above, but which the majority of Americans have supported because we understood and agreed with what was at stake.

This is not that, and it never will be that. This is the action of a one unhinged man with unlimited power granted to him by the most irresponsible Congressional bloc in our lifetimes. Our founders attempted to build a decision structure that precluded exactly the situation in which we currently find ourselves, but Trump has hacked that system, and the costs in lives and dollars of that hack are building each day.

Jared Bernstein is a former chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers under President Joe Biden. He is a senior fellow at the Council on Budget and Policy Priorities. Please consider subscribing to his Substack.

Reprinted with permission from Econjared.

- War On Iran Is Still A War Even When Gutless Republicans Insist It Isn't ›

- No Justification: Trump Won't Explain His Feckless And Bellicose Iran Policy ›

Start your day with National Memo Newsletter

Know first.

The opinions that matter. Delivered to your inbox every morning