By Meredith Blake, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

NEW YORK — There wasn’t much in Trevor Noah’s childhood in Johannesburg to suggest that he would one day host America’s preeminent satirical program, starting with apartheid-era South Africa having virtually no tradition of professional comedy — nor, for that matter, free speech.

Then there was Noah’s strictly limited pop-culture diet, which consisted of reruns of Murder, She Wrote and Knight Rider he watched with his mother. Years later, when a friend urged him to watch Eddie Murphy’s Raw, Noah was baffled: The guy from The Nutty Professor did stand-up?

By his own account, Noah was a “nerdy little child” who spent most of his time indoors reading voraciously — everything from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory to electronics manuals.

“That was my world,” says the 31-year-old late one evening in his sparsely decorated office. “I just consumed — that’s all I’ve ever been, a consumer of information.”

It’s a quality that will serve him well at The Daily Show, where Noah will take over for Jon Stewart on Monday night.

The comedian’s rise from the township to the pinnacle of American comedy is one of the more unexpected developments in an era of tremendous upheaval for late-night television. Before he was named Stewart’s successor in March, Noah had made only a handful of appearances as a contributor on “The Daily Show” and was little known in the United States.

In contrast, the man he will be replacing is a widely revered comedian who over the course of 16 years on the job transformed The Daily Show into essential election-year viewing and the Emmy-winning jewel in Comedy Central’s crown

Noah may not yet have the recognition of a Chris Rock or an Amy Schumer — names who were floated as possible successors to Stewart — but there is little doubt that he will bring a unique perspective on race, politics and cultural identity to The Daily Show at a time when such issues dominate the news.

Born to a black mother and white father whose relationship was illegal under apartheid, Noah has mined his tumultuous upbringing for laughs in a stand-up act that blends comedy with tragedy. “I was born a crime,” he has said.

Since he first began performing in his early 20s, Noah has gained an international reputation for his irreverent take on charged topics such as Western perceptions of Africa, his country’s scandal-prone politicians and, especially, race. And though Noah is firmly in the millennial generation coveted by television executives, he has a hard-earned wisdom and maturity that transcends his young age.

“I was born in the middle. I’ve always lived in the middle. I’ve been an outsider and an insider,” he says. “I have the ability to see both sides, and then I try to find the truth.”

In February, Stewart announced he would be stepping down from The Daily Show, stunning the loyal fans who had hoped he’d continue to be their voice of reason through the 2016 election and rattling executives at Comedy Central.

“There was a moment of panic, of course,” concedes the network’s president, Michele Ganeless. “We knew the day would come. Obviously, we hoped it would come later rather than sooner, but it came sooner.”

Stewart’s bombshell also happened to land two months after the final broadcast of The Colbert Report and just a few weeks into the run of its replacement at 11:30, The Nightly Show With Larry Wilmore. John Oliver, who had successfully anchored The Daily Show during Stewart’s Rosewater hiatus in 2013 and was widely viewed as his heir apparent, had been wooed away by HBO a year earlier.

“It wasn’t perfect timing for sure,” says Ganeless. “If you had told me five years ago that in the same 12-month period, Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert would leave the air and we would still be standing, I wouldn’t have believed you.”

Without any obvious subs on the bench, the network chose to look at Stewart’s departure “as an opportunity to bring in someone fresh and different,” says Kent Alterman, president of content development and original programming. “We would be setting ourselves up for failure if we thought, ‘Oh, let’s find a young version of Jon Stewart.’ It doesn’t exist.”

By this point, Noah’s profile in the U.S. was already on the rise. He’d toured in 40 states, filmed a stand-up special called “Trevor Noah: African American,” and made Jay Leno howl on The Tonight Show — the first South African comedian to do so.

In December, he joined The Daily Show as a contributor. His first bit, called “Spot the Africa,” brilliantly flipped Western stereotypes of a continent “full of AIDS huts and starving children” to comment on the contentious state of race relations in the U.S. “I never thought I’d be more afraid of police in America than in South Africa,” he joked. “It kind of makes me a little nostalgic for the old days back home.”

Though the network put out feelers to other potential hosts, Ganeless says that Noah was “at the top of the list from the beginning.”

His multicultural background — a rarity in what remains the overwhelmingly white, male world of late night — was a bonus, not a prerequisite, says Ganeless. “We talked to white men and we talked to black men, and we talked to white women and black women. We found the right person.”

Noah knew he was up for the job but also heard the other “amazing names” being considered and knew not to get his heart set on anything. “The longer I stayed in the running, the happier I got,” says the comedian, who learned he’d be the new host of The Daily Show while on tour in Dubai. “I got the news and then my world got turned upside down.”

Noah’s childhood was divided between his mother’s home in Soweto and his father’s residence in the Hillbrow neighborhood, then entirely white. His parents, who met as part of an underground, desegregated social scene in Johannesburg, never married; it was against the law. His Swiss father worked as a chef and managed a grocery store, and his mother was a secretary.

The comedian developed strategies for dealing with the suspicion aroused by his skin color. He pretended his mother was the maid, played along when people assumed he was albino and walked across the street from his father. (That is, until his father moved away, first to Cape Town, then to Switzerland; they had little contact for many years.)

Noah says the experience of living between, if never entirely within, two wildly different worlds turned him into a “cultural chameleon” and an expert mimic — skills he wields impressively onstage, where he slides between various American, English, Australian, and South African accents with ostentatious ease.

“You find that if you can blend in,” says Noah, who also speaks a half-dozen or so languages, “people spend less time asking you why you aren’t one of them.”

There was no money for college, and in his late teens and early 20s Noah began to gravitate toward — doing a bit of acting and working as a radio DJ. He stumbled into comedy, quite literally, about 10 years ago, when he was thrust onstage during a raucous visit to a comedy night at a Johannesburg bar.

Within a few years, he’d risen to the top of South Africa’s small comedy scene, hosting his own talk show and regularly selling out the country’s largest theaters. The documentary You Laugh But It’s True, chronicles Noah’s meteoric ascent, and the resentment it created among some of his peers. In one scene, an older white comedian calls Trevor “arrogant,” and it’s hard not to cringe.

“There was a general resentment of comedians of color rising very rapidly,” Noah says, “as there was a resentment of people of color rising rapidly in any sphere in South Africa.”

More dire than racism was the violence that touched Noah’s life in 2009, when his mother was shot in the head by his former stepfather. She survived, as did her sense of humor, says Noah. “Comedy gives you the power to not take things seriously. When you laugh at somebody, when you laugh at something, all of a sudden, it seems surmountable.”

Still, there are few life experiences that can prepare one for becoming the target of an angry Internet mob. The excitement that followed the news of Noah’s hiring in March gave way almost instantly to a firestorm over tweets, written by Noah as far back as 2009, that many viewed as misogynistic and anti-Semitic.

Noah was taken aback by the criticism and viewed the tweets as the work of a less polished and mature comedian. “It’s very difficult for somebody to go back into your past or into things you’ve done and no longer do and then tell you to change. It’s like someone telling you to quit smoking, and you quit smoking seven years ago.”

Now that the virtual dust has settled, the outrage seems misguided. In person, Noah is less reminiscent of a frat boy than the cute, earnest guy in your philosophy class who stayed up late drinking coffee and talking about Camus.

He says things like “as human beings we have children, so that we ourselves can learn again” and speaks using constant metaphors and analogies. (Watching Raw as an aspiring comedian was like “someone showing you a skyscraper when you’re busy building Legos”; society is always moving in the direction of progress, “like an iPhone.”) It’s a trait he says comes from growing up in a Bible-reading household where “everything was a parable.”

In the weeks since Stewart signed off in early August, nearly every waking hour of Noah’s day has been consumed by a blitz of promotion, writing sessions and test shows.

Throughout the process, Noah has impressed his new colleagues with his “self-possession and charm and unflappable nature,” says Alterman, who adds that “it’s possible that he’s a cyborg.”

Executive producer Steve Bodow praises Noah as a “quick study” in American politics, which comes in handy as the race for the White House gains momentum. He’s also developing a voice distinct from that of his predecessor, who was fond of calling out political hypocrisy and media distortions.

“Trevor approaches it more as someone who’s new to the process. There’s just as much comedic potential with that,” says Bodow, one of the key Stewart-era players who will remain at the show under its new leader.

As for contact between the hosts, Noah says, “I’m conscious of using my ‘call a friend’ very sparingly.”

By way of explanation, he invokes another metaphor: As a child, Noah would ask his mother for help locating misplaced belongings and she would gently steer him in a more self-reliant direction.

“She would always say, ‘If you look like you know I’m going to come and look for you, you’ll never find it. Look like I’m never coming, and then you will find what you need.’ That’s how I see it with Jon Stewart. I go look for the answer as if Jon Stewart doesn’t exist.”

(c)2015 Los Angeles Times. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

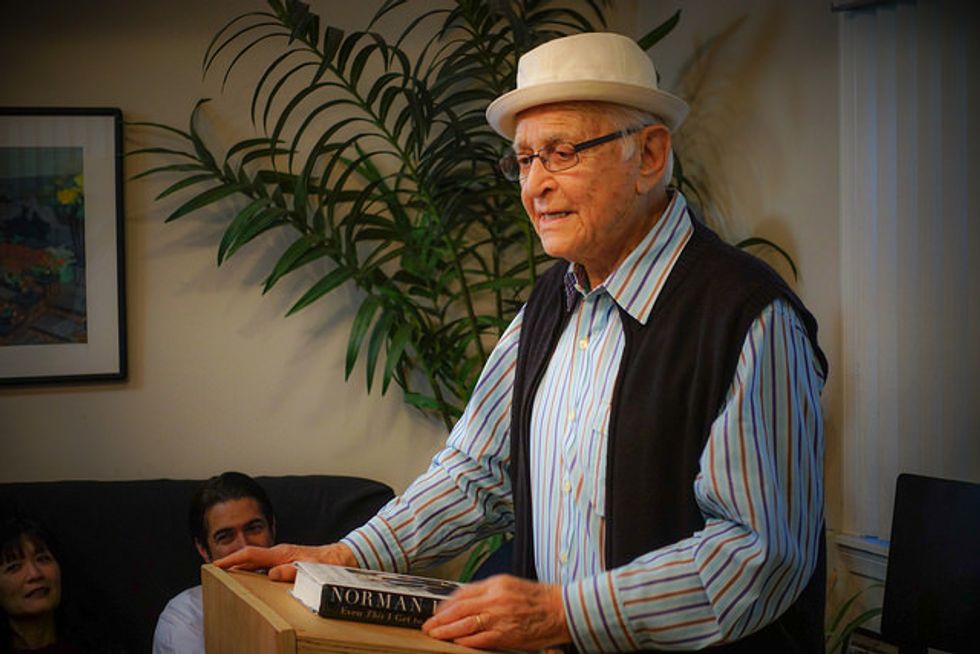

Photo: Peter Yang/Comedy Central