In This Season Of Feasting, Let's Celebrate Agriculture, Not Agribusines

In December 1972, I was part of a nationwide campaign that came tantalizingly close to getting the U.S. Senate to reject Earl Butz, Richard Nixon's choice for secretary of agriculture.

A coalition of grassroots farmers, consumers, and scrappy public interest organizations (like the Agribusiness Accountability Project that Susan DeMarco and I then headed) teamed up with some gutsy, unabashedly progressive senators to undertake the almost impossible challenge of defeating the cabinet nominee of a president who'd just been re-elected in a landslide.

The 51 to 44 Senate vote was so close because we were able to expose Butz as ... well, as butt-ugly — a shameless flack for big food corporations that gouge farmers and consumers alike. We brought the abusive power of corporate agribusiness into the public consciousness for the first time, but we had won only a moral victory, since there he was, ensconced in the seat of power. It horrified us that Nixon had been able to squeeze Butz into that seat, yet it turned out to be a blessing.

An arrogant, brusque, narrow-minded and dogmatic ag economist, Butz had risen to prominence in the small (but politically powerful) world of agriculture by devoting himself to the corporate takeover of the global food economy. He was dean of agriculture at Purdue University, but also a paid board member of Ralston Purina and other agribusiness giants. In these roles, he openly promoted the preeminence of middleman food manufacturers over family farmers, whom he disdained.

"Agriculture is no longer a way of life," he infamously barked at them. "It's a business." He callously instructed farmers to "Get big or get out" — and he then proceeded to shove tens of thousands of them out by promoting an export-based, conglomeratized, industrialized, globalized and heavily subsidized corporate-run food economy. "Adapt," he warned farmers, "or die." The ruination of farms and rural communities, Butz added, "releases people to do something useful in our society."

The whirling horror of Butz, however, spun off a blessing, which is that innovative, free-thinking, populist-minded and rebellious small farmers and food artisans practically threw up at the resulting "Twinkieization" of America's food. They were sickened that nature's own rich contribution to human culture was being turned into just another plasticized product of corporate profiteers.

"The central problem with modern industrial agriculture... (is) not just that it produces unhealthy food, mishandles waste, and overuses antibiotics in ways that harm us all. More fundamentally, it has no soul," said Nicholas Kristof, a New York Times columnist and former farm boy from Yamhill, Oregon. Rather than accept that, they threw themselves into creating and sustaining a viable, democratic alternative. The Good Food rebellion has since sprouted, spread and blossomed from coast to coast.

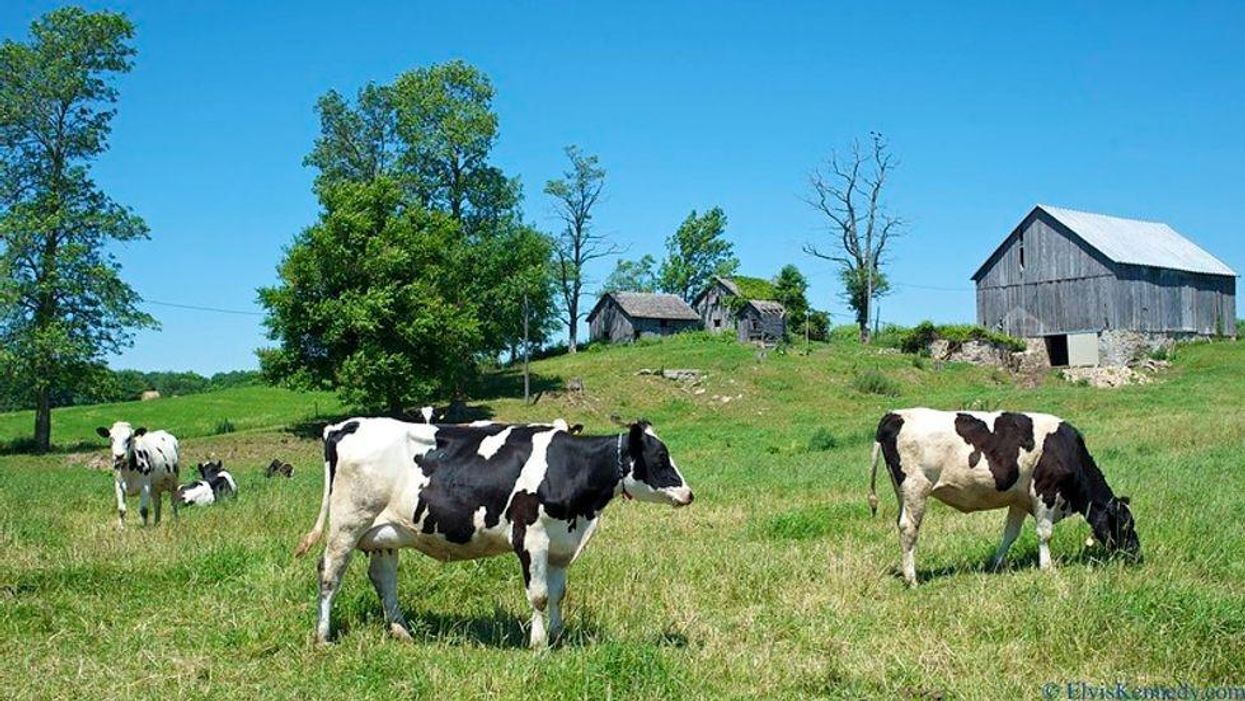

This transformative grassroots movement rebuts old Earl's insistence that agriculture is nothing but a business. It most certainly is a business, but it's a good business — literally producing goodness — because it's "a way of life" for enterprising, very hardworking people who practice the art and science of cooperating with Mother Nature, rather than always trying to overwhelm her. These farmers don't want to be massive or make a killing; they want to farm and make delicious, healthy food products that help enrich the whole community.

This spirit was summed up in one simple word by a sustainable farmer in Ohio, who was asked what he'd be if he wasn't a farmer. He replied: "Disappointed." To farmers like these, food embodies our full "culture" — a word that is, after all, sculpted right into "agriculture" and is essential to its organic meaning.

Although agriculture has forestalled the total takeover of our food by crass agribusiness, the corporate powers and their political hirelings continue to press for the elimination of the food rebels and ultimately to impose the Butzian vision of complete corporatization. This is one of the most important populist struggles occurring in our society. It's literally a fight for control of our dinner, and it certainly deserves a major focus as you sit down to your holiday dinners this year.

To find small-scale farmers, artisans, farmers markets, and other resources in your area for everything from organic tomatoes to pastured turkey, visit www.LocalHarvest.org.

To find out more about Jim Hightower and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators webpage at www.creators.com.