Why Didn't Justice Department Defend Alabama Prisoners From Starvation?

Supporters of Alabama prison strikers in protest at state house

This is the third in a series of columns about the current crisis in Alabama’s prisons. Read the first here and the second here.

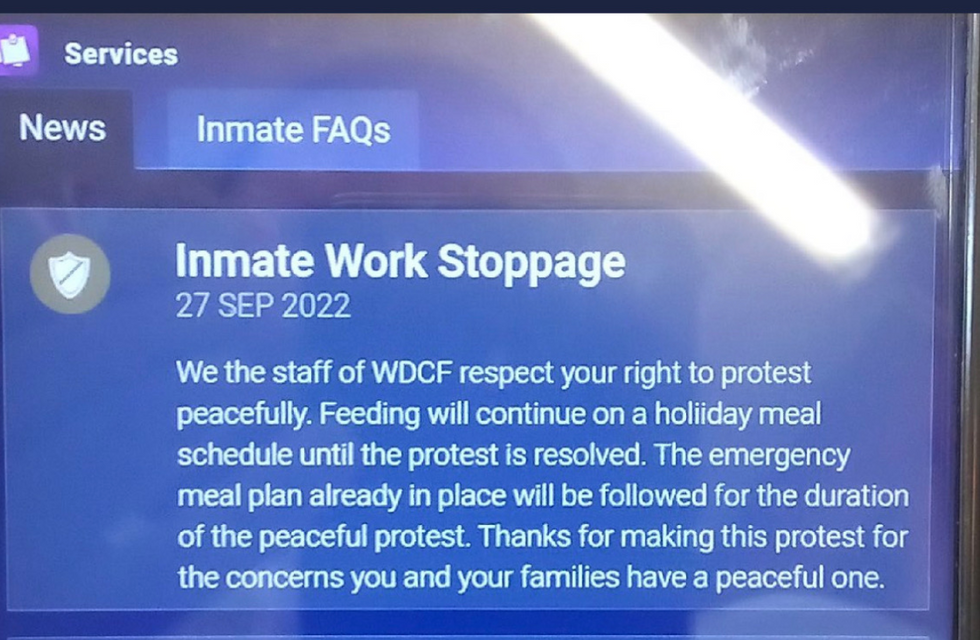

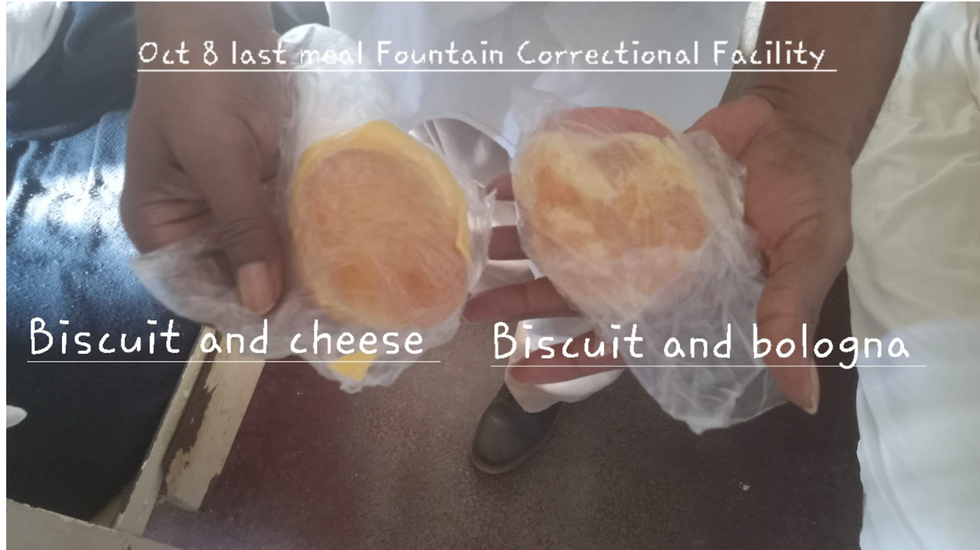

What happened in Alabama prisons during the most recent work stoppage — the Alabama Department of Corrections served severely reduced portion sizes only twice a day, from September 26 to October 26, 2002 — was nothing less than the weaponization of food by a government against its own citizens.

The last time state actors played Hunger Games against their own in the United States was the Civil War, when President Lincoln issued “General Orders No. 100: Instructions for the Government of the Armies of the United States in the Field,” commonly known as the “Lieber Code” after its main author Francis (Franz) Lieber.

The Lieber Code promulgated the essential rules of engagement for Union Army soldiers during the Civil War. Those rules specifically stated that it was “lawful to starve the hostile belligerent, armed or unarmed”... so as to hasten on the surrender.”

The excuse provided by the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC), namely that they didn’t have the correctional staff to cover the positions vacated by the incarcerated workers, is unavailing.

While it’s true that inmate workers were not appearing for their work assignments, posts didn’t go unmanned. Starting around the third day of the strike, the ADOC forced participants in the state’s work release program to go back inside prisons and prepare the meals. The Alabama Department of Corrections forced scabs to come in and break the picket line by working inside.

One man on work release reported that a lieutenant “made [him]” enter a prison and prepare meals or lose his work release status. “It was either come over here or go over to lock up,” he said in an interview.

According to Frank Ozment, a Birmingham, Alabama attorney with years of experience representing prisoners in the Yellowhammer State, taking work release inmates back inside has happened only once before, during the pandemic, when men from the Frank Lee Community Based Facility/Work Center were taken to Draper Correctional Facility in Elmore, Alabama to build an intake center.

When the work release employees realized that COVID patients were housed at that particular facility, they balked and the matter was eventually resolved. It’s important to note that taking work release prisoners to Draper Correctional Facility didn’t involve a work stoppage nor were the tasks assigned to these individuals supposedly being carried out by overworked officers.

The guards were less than enthusiastic about the strike or an expectation that they fill in essential roles; indeed, some may have refused to pitch in. According to screenshots provided by an unnamed source, one ADOC officer posted to Facebook: “They could wade knee deep in shit and starve before I would cook them even a morsel of food!!! When they got a bellyful of living in filth they could clean everything back up too…I wouldn’t lift a finger!!!”

It’s not as if the human rights violations occurring in the facilities seemed to bother the entire guards corps. Memes poking fun at starvation, comments about serving the wards only bread and water proliferated under posts about the strike from accounts purporting to be correctional officers proliferated during the strike.

Of paramount importance in understanding what unfolded during that strike is that neither the State of Alabama nor ADOC has ever directly refuted the claims of inadequate meals. Through counsel, the state of Alabama denied the allegations by claiming inmates' representations of the content and quantity of meals were inaccurate. Kelly Betts, spokesperson for the Alabama Department of Correction, did not answer questions posed to her via email about the meals and the effects of reduced calories on the people who ate them.

However, if the pictures are not representative of what was actually distributed as meals and the claims of inmates are not describing what was served to them accurately, then the state can — and should — provide evidence of what was served. There’s no reason to suspect that these records don’t exist or are even difficult to collect.

Stacey Lee George, a former Alabama correctional officer who resigned last month and worked in the kitchen during his 13-plus year career, reports that kitchens maintain these records on computers. If the ADOC provided sufficient calories during the shutdown, they have the evidence as a matter of daily practice. They’re simply not providing that evidence in any forum. A Freedom of Information Act request seeking copies of all records indicating what was served has not yet been responded to by the Alabama Department of Corrections.

Neither the spacing of the distribution of the meals nor their content was a consequence of the strike’s circumstances. The meals were intentionally prepared and delivered. The state of Alabama and its Department of Correction used outlawed tactics of war to manage people who have been entrusted to their care. What happened in Alabama prisons in September and October violated the prohibited use of food as a method of punishment. It was an attempt to harm the wards and starve them into submission.

And the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) is complicit in this gastronomical gambit, all while the biggest and most powerful law enforcement agency in the country is supposed to be protecting people from unlawful abuse by state agencies like ADOC.

On December 9, 2020, the DOJ filed suit against the State of Alabama under the Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act (CRIPA) alleging that the conditions in Alabama prisons were so bad that they violated inmates’ Eighth Amendment and Fourteenth Amendment rights to due process and to be free from cruel and unusual punishment. The case has been pending for the past two years.

Eleven days into the strike, on October 7, 2022, 37 inmates filed a motion to intervene — to become parties to the action to have their complaints heard — in the DOJ suit. And instead of taking action to assure that inmates were fed during the stoppage, the DOJ opposed this motion to intervene, arguing that allowing the inmates to enter the case at that point would disrupt the discovery process.

In the responses filed since October 7, 2022, DOJ provided no other reason why the inmates shouldn’t be allowed to become plaintiffs, nor did the department deny that the meals were as meager and infrequent as alleged. None of the DOJ lawyers even contacted attorneys for the intervening plaintiffs. DOJ failed to make a statement in its response to the inmates’ Motion to Intervene that starving prisoners is unlawful.

It’s not clear that the DOJ took any action to assure the prisoners were fed; Aryele N. Bradford, spokeswoman for the DOJ’s Office of Public Affairs, said in an email that the DOJ will not comment on pending litigation.

The department’s silence and apparent inaction isn’t borne of strategy; it’s vanity.

“The one thing the government doesn't like to do is lose. And that's a good thing. But they're not going to do anything that they don't think is a slam dunk. I mean, that's just been my experience with them almost throughout my career,” said Ozment.

Indeed, legal scholars agree. “For DOJ, success is measured solely by winning percentage in the courts; the basis of a favorable decision does not matter, and winning is an end in itself. For the agency, success is a function of: (a) winning percentage not just in the courts, but in an overall enforcement effort most of which occurs outside the judiciary; and (b) the advancement of a particular policy agenda…” wrote Neal Devins, professor of law and government at the College of William and Mary and Michael Herz, professor of law at Yeshiva University's Cardozo School of Law in a 2003 article in the Journal of Constitutional Law.

In the responses filed since October 7, 2022, DOJ provided no other reason why the inmates shouldn’t be allowed to become plaintiffs, nor did the department deny that the meals were as meager and infrequent as alleged. It’s not clear that the DOJ took any action to assure the prisoners were fed. An email asking that exact question was posed to four separate lawyers representing the DOJ in this matter and none of them replied.

It’s not that the claims of retaliation with food don’t belong in the pending litigation. CRIPA confers standing on the Attorney General to institute a civil action to enforce any existing constitutional and federal statutory rights of people who are confined within institutions.

In the 2020 lawsuit, the United States alleges that defendants have violated the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments, but the most recent problems add another constitutional dimension. To the extent that ADOC served skimpy trays as retribution for engaging in a protest that the department itself admits was peaceful, the substandard meals implicated inmates’ First Amendment rights.

Whatever particular rights violation the DOJ wants to concentrate on, lawyers for the agency filed the suit ostensibly to protect the incarcerees from harm. To learn that they’re being systematically starved and then oppose any kind of relief for that deprivation undermines the DOJ’s stated commitment to protecting people in institutions and may even introduce a conflict of interest in the currently pending litigation.

The irony of the DOJ’s prioritization of winning over taking a moral stand is that it may undermine their chances of winning. The DOJ depends on inmates to testify and provide evidence in their original case but it’s clear now that there’s little incentive to do so.

One of the intervening plaintiffs, Inmate Billy Crowe, has testified and reported problems to the DOJ through an established hotline. After he moved to intervene in the DOJ’s case during the strike, Crowe’s been beaten severely several times, once while two guards watched, according to his sworn statement made in support of his motion to amend, alter or vacate Judge Proctor’s order denying his attempt to get some relief.

“This is getting old,” said Ozment, who represents Crowe.

And from the department’s response to the mass starvation, Crowe and other inmates know that the DOJ isn’t their champion.

According to one incarcerated man whose identity is being withheld because of fear of retaliation, the people confined in Alabama have little hope that anyone on the outside will help them.

“I'm starting to see a lot of guys being more inspired to say, you know what..the courts have turned their backs on us and shut down the parole board, and Alabama has shut down. Society has been shut down," he said. "So now it's time for us to shut down on them and let them run this prison system themselves without us. They already know they cannot run it.”

Whether these men and women will ultimately testify for the DOJ remains to be seen.

They may testify in another proceeding. According to Ozment, who represented one of the intervening plaintiffs, inmate Billy Crowe, Judge Proctor’s decision doesn’t prevent the prisoners’ from initiating a new action to address the problems with food and ultimately establish the law regarding the minimum requirements for prison meals that courts have sidestepped so far. Ozment is considering representing prisoners in such an action if he can find financial backing.

Weaponization of food works -- and that’s its peril and promise. Organizers paused the Alabama prison strike when it became clear that men were becoming ill as a result of the lack of food. It’s not that the strikers didn’t send their message; they did. Prisons can’t function without the laborers willing to do the work — and the current assemblage of guards have indicated that they’re not so willing.

And the Department of Justice is even less willing to do anything to correct these situations.

Chandra Bozelko did time in a maximum-security facility in Connecticut. While inside she became the first incarcerated person with a regular byline in a publication outside of the facility. Her “Prison Diaries" column ran in The New Haven Independent, and she later established a blog under the same name that earned several professional awards. Her columns now appear regularly in The National Memo.