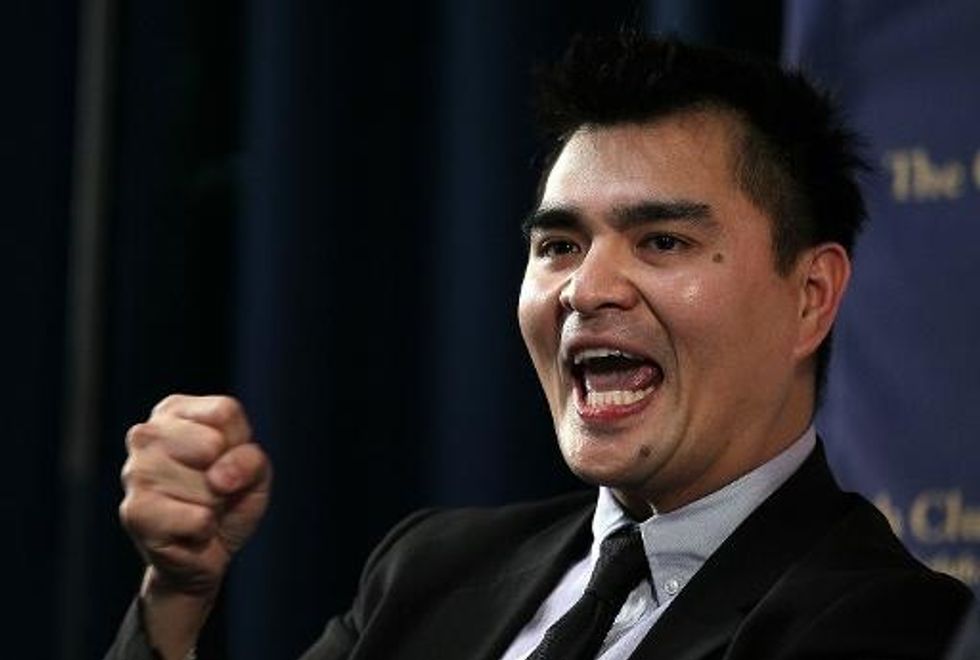

Detentions A ‘Risk’ Faced By Undocumented U.S. Migrants: Activist

Washington (AFP) — Immigration activist Jose Antonio Vargas said Wednesday his detention by U.S. border agents in Texas was just an example of the risks that undocumented immigrants face every day in America.

Vargas, 33, a Philippines-born prize-winning journalist, was handcuffed and questioned by Border Patrol officers Tuesday as he prepared to board a domestic flight to Los Angeles in the border city of McAllen.

He was ordered to appear before an immigration judge, but not before news of his detention triggered a media storm amid an influx of tens of thousands of Central American children over the U.S.-Mexico border.

“I’ve been travelling around the country for the past three years” without incident using a Philippine passport that lacks a US visa, said Vargas, who came out as an undocumented immigrant in a widely-read 2011 essay.

But he told CNN he was unaware — on his first visit to Texas to investigate the plight of child immigrants — that the border there is a “militarized zone” with checkpoints scattered as far as 45 miles (70 kilometers) from the border.

“When you fly through JFK … there’s no Border Patrol agent checking your passport when you go through,” explained Vargas, referring to New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport.

“But here, in south Texas, that’s what happened — and, you know, people need to understand that if you are undocumented in this country, that’s the risk you take.”

– ‘Look in their eyes’ –

Asked about the migrant youngsters he encountered in Texas, Vargas said: “All you have to do is look in the eyes of these children to know that they have been through some sort of hell.”

Vargas was 12 years old in 1993 when his young mother put him on a flight in Manila to be raised by his grandparents in California, in hopes that he could live the American dream.

He went on to join the Washington Post, where he was part of a team that won a Pulitzer Prize in 2008, then came out in a 2011 essay in the New York Times as one of America’s estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants.

What happened since that Times essay was the subject of “Documented,” a feature documentary written, produced and directed by Vargas, which got its world premiere in June last year.

U.S. authorities are currently grappling with a surge of unaccompanied and undocumented children streaming over the Mexican border that has inflamed an already heated debate over immigration policy and border security.

Over 57,000 youngsters have illegally entered the United States since October, the majority arriving in Texas, according to official U.S. data. They are mostly from Central America, fleeing poverty and violence.

AFP Photo / Justin Sullivan

Interested in national news? Sign up for our daily email newsletter!