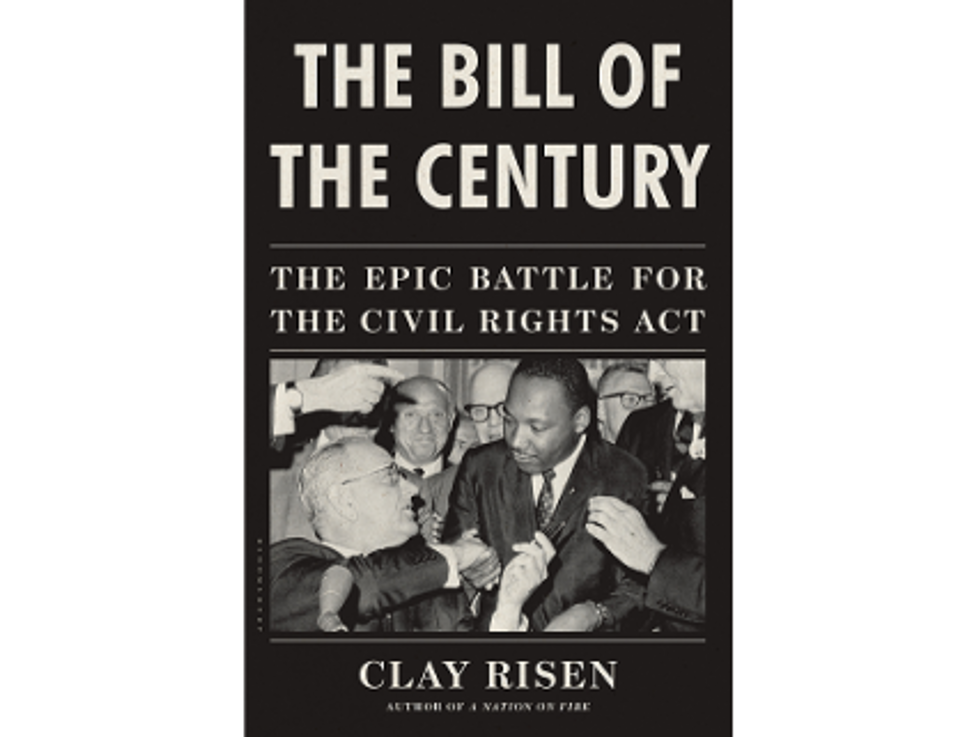

Weekend Reader: ‘Bill Of The Century: The Epic Battle For The Civil Rights Act’

Today the Weekend Reader brings you Bill of the Century: The Epic Battle for the Civil Rights Act by Clay Risen, editor of The New York Times op-ed section. Bill of the Centurydetails the arduous mission of civil rights leaders to pass a bill that granted equal rights to millions of Americans regardless of race, sex, or religion. Risen explores the long list of other important contributors who drafted the bill and pushed it through Congress, led by Martin Luther King, Jr., Robert F. Kennedy, President John F. Kennedy, and President Lyndon B. Johnson.

You can purchase the book here.

While in Birmingham, [Assistant Attorney General Burke] Marshall had spent some time talking with Dick Gregory, a black comedian and outspoken civil rights activist. Gregory said that part of the administration’s problem was that the Kennedys never actually talked with black people. Marshall relayed the suggestion to Robert Kennedy. The attorney general asked if Marshall could set up a meeting with the author James Baldwin, whose essay “Letter from a Region of My Mind” he had read in the New Yorker. Marshall got in touch with Baldwin, who agreed to come to Washington to meet Kennedy on May 23.

When the day arrived, though, Baldwin’s plane was delayed, and by the time he got to Kennedy’s northern Virginia home, the attorney general had only twenty minutes to talk. Kennedy began by admitting that the proposals under consideration were focused on issues facing Southern blacks and would do little to help those in the Northern cities. What, he asked Baldwin, should be done? Baldwin offered to assemble a group of black activists and intellectuals for Kennedy to meet with. By chance, Kennedy said, he was going to be in New York the next day—why not set up a get-together that afternoon?

The next morning, Kennedy, Marshall, and Oberdorfer flew to New York for a meeting with the heads of several major five and dimes, theaters, and department stores—Woolworth’s, Kress, J. C. Penney, McCrory, Sears—to discuss what they could do to desegregate their branches in the South. Kennedy came away with noncommittal responses, assurances that the chains would do the best they could but that they could not promise anything that would undermine their profits, which in the South, they insisted, meant acceding to customers’ demands that they remain segregated.

![]()

Kennedy and his aides then headed to his father’s apartment at 24 Central Park West for the meeting with Baldwin’s hastily assembled focus group. If not a who’s who of the black community in New York, it was a good cross-section: Kenneth Clark, the eminent psychologist from the City College of New York; the singers Harry Belafonte and Lena Horne; the playwright Lorraine Hansberry; Jerome Smith, a twenty-four-year-old veteran of the Freedom Rides; Baldwin’s brother David and a friend of his, Thais Aubrey; Martin Luther King Jr.’s lawyer, Clarence Jones; and the Urban League activist Edwin C. Berry. (The white actor Rip Torn, who was active in civil rights, was also there.)

Clark and Berry were supposed to set an intellectual, measured tone for the meeting, but it derailed almost immediately. “In that moment, with the situation in Birmingham the way it was,” said Horne later, “none of us wanted to hear figures and percentages and all that stuff. Nobody even cared about expressions of goodwill.”

Smith, a passionate man with a pronounced stammer, began by saying, “Mr. Kennedy, I want you to understand I don’t care anything about you or your brother.” He said it was obvious that the Kennedys did not care about Southern protesters. In fact, he said, just being in the same room as the attorney general made him sick to his stomach.

Kennedy was visibly offended, but rather than engage with Smith, he tried to ignore him. He began addressing Baldwin, but Hansberry cut him off. “You’ve got a great many very, very accomplished people in this room, Mr. Attorney General. But the only man who should be listened to is that man over there,” she said, pointing at Smith. The young Freedom Rider began explaining what he had lived through in the South, emphasizing how little the federal government had done to help him.

Eventually Kennedy interrupted him. “Just let me say something,” he said.

“Okay,” said Smith, “but this time say something that means something. So far you haven’t said a thing!”

Kennedy tried to explain the bills, but Smith just scoffed. The situation was far too dire. He was a nonviolent man, he said, but he was unsure for how long. “When I pull the trigger, kiss it goodbye!”

Trying to inject some balance to the conversation, Baldwin asked Smith if he would ever fight for his country. “Never!” Smith said.

That drove Kennedy over the edge. He had been just a few years too young to fight in World War II, the war that had killed one of his brothers and made a hero of another. “How could you say that?” he demanded. “Bobby got redder and redder and redder, and in a sense accused Jerome of treason,” recalled Clark.

Kennedy asked for ideas. Baldwin said the president should personally escort students into the University of Alabama who were being blocked by Governor Wallace. He should get rid of J. Edgar Hoover at the FBI. The Department of Justice should be more aggressive in Birmingham. The attorney general insisted that he was working closely with King, which brought forth peals of cynical laughter.

Eventually Kennedy ran out of the energy to both respond to the attacks and keep his anger in check, and he just sat there quietly as Baldwin’s panel took turns berating him, his brother, and the federal government. “It became really one of the most violent, emotional, verbal assaults that I had ever witnessed before or since,” said Clark. Finally, after three hours, the meeting broke up.

The encounter had a profound effect on Kennedy. At first he was just angry. When Belafonte apologized afterward for the group’s hostility and said he agreed with Kennedy, the attorney general glared at him and said, “How could you just sit there and not say anything?” After returning to Washington, he sat down for a debriefing with Schlesinger. “They don’t know anything,” he said. “They don’t know what the laws are—they don’t know what the facts are. They don’t know what we’ve been doing or what we’re trying to do. You couldn’t talk to them as you can to Roy Wilkins or Martin Luther King. They didn’t want to talk that way. It was all emotion. Hysteria. They stood up and orated. They accused. Some of them wept and walked out of the room.”

But over the next several days and weeks, Kennedy began to change. As his own anger faded, he found that the evident passion and stinging sense of injustice he has witnessed in Baldwin’s group had left an impression on him. “The more I saw him after this,” Belafonte recalled, “the more he no longer had questions that were just about the specifics of federal government intervention, or the civil rights strategy of the moment. He began to move to broader philosophical areas, began to know more about cause and effect and why.” Asked later to illustrate Kennedy’s education in civil rights, Marshall shot his hand straight up. Ed Guthman saw it, too. “After a day or two, Bob’s attitude about the meeting began to shift. He had never heard an American citizen say he would not defend the country and it troubled him. Instead of repeating, as he had, ‘Imagine anyone saying that,’ he said, ‘I guess if I were in his shoes, if I had gone through what he’s gone through, I might feel differently about this country.’”

On May 29, Robert Kennedy paid a surprise visit to Johnson’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity. Kennedy sat quietly for a few minutes as NASA administrator James Webb gave a presentation of his agency’s progress. Then Kennedy began to cross-examine Webb, quickly establishing that NASA, which handled billions of dollars in contracts annually, had just two people—or one and a half, since one of them was Webb, who had other duties—making sure that the companies it did business with did not discriminate. “I don’t think this gentleman over here that spent a year and a half on this program—if he has, evidently, some other responsibilities, I don’t think he is going to get that job done,” Kennedy said. “He has got $3.9 billion worth of contracts.”

Webb meekly tried to defend himself. “I would like to have you take enough time to see precisely what we do.”

But Kennedy blew past him. “I am trying to ask some questions. I don’t think I am able to get the answers, to tell you the truth.”

At that point Johnson stepped in to defend Webb. “Do you have any other questions?” he asked Kennedy.

“That is all for me,” said the attorney general, and he stalked from the room.

Kennedy’s performance served many purposes, including venting steam from his encounter in New York as well as getting in some sucker punches against his nemesis, Lyndon Johnson. But it was also typical of the way Kennedy came to a new passion—intensely, with something to prove, enemies to make, and battles to be won. “Racial justice was no longer an issue in the middle distance,” wrote Schlesinger. “Robert Kennedy now saw it face to face, and he was on fire.”

If you enjoyed this excerpt, you can purchase the full book here.

From Bill of the Century: The Epic Battle for The Civil Rights Act by Clay Risen, Copyright © 2014 by Clay Risen. Published by Bloomsbury Press. Reprinted with permission.