Amid Climate Change, Dangerous War Games In The Arctic

Reprinted with permission from TomDispatch.

In early March, an estimated 7,500 American combat troops will travel to Norway to join thousands of soldiers from other NATO countries in a massive mock battle with imagined invading forces from Russia. In this futuristic simulated engagement — it goes by the name of Exercise Cold Response 2020 — allied forces will “conduct multinational joint exercises with a high-intensity combat scenario in demanding winter conditions,” or so claims the Norwegian military anyway. At first glance, this may look like any other NATO training exercise, but think again. There’s nothing ordinary about Cold Response 2020. As a start, it’s being staged above the Arctic Circle, far from any previous traditional NATO battlefield, and it raises to a new level the possibility of a great-power conflict that might end in a nuclear exchange and mutual annihilation. Welcome, in other words, to World War III’s newest battlefield.

For the soldiers participating in the exercise, the potentially thermonuclear dimensions of Cold Response 2020 may not be obvious. At its start, Marines from the United States and the United Kingdom will practice massive amphibious landings along Norway’s coastline, much as they do in similar exercises elsewhere in the world. Once ashore, however, the scenario becomes ever more distinctive. After collecting tanks and other heavy weaponry “prepositioned” in caves in Norway’s interior, the Marines will proceed toward the country’s far-northern Finnmark region to help Norwegian forces stave off Russian forces supposedly pouring across the border. From then on, the two sides will engage in — to use current Pentagon terminology — high-intensity combat operations under Arctic conditions (a type of warfare not seen on such a scale since World War II).

And that’s just the beginning. Unbeknownst to most Americans, the Finnmark region of Norway and adjacent Russian territory have become one of the most likely battlegrounds for the first use of nuclear weapons in any future NATO-Russian conflict. Because Moscow has concentrated a significant part of its nuclear retaliatory capability on the Kola Peninsula, a remote stretch of land abutting northern Norway — any U.S.-NATO success in actualcombat with Russian forces near that territory would endanger a significant part of Russia’s nuclear arsenal and so might precipitate the early use of such munitions. Even a simulated victory — the predictable result of Cold Response 2020 — will undoubtedly set Russia’s nuclear controllers on edge.

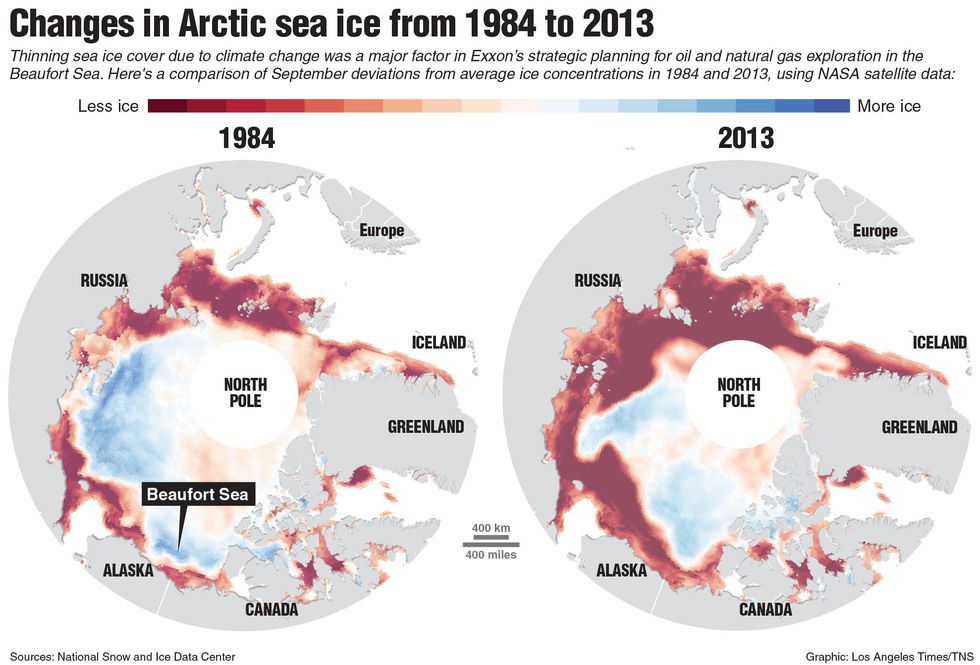

To appreciate just how risky any NATO-Russian clash in Norway’s far north would be, consider the region’s geography and the strategic factors that have led Russia to concentrate so much military power there. And all of this, by the way, will be playing out in the context of another existential danger: climate change. The melting of the Arctic ice cap and the accelerated exploitation of Arctic resources are lending this area ever greater strategic significance.

Energy Extraction in the Far North

Look at any map of Europe and you’ll note that Scandinavia widens as it heads southward into the most heavily populated parts of Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden. As you head north, however, it narrows and becomes ever less populated. At its extreme northern reaches, only a thin band of Norway juts east to touch Russia’s Kola Peninsula. To the north, the Barents Sea, an offshoot of the Arctic Ocean, bounds them both. This remote region — approximately 800 miles from Oslo and 900 miles from Moscow — has, in recent years, become a vortex of economic and military activity.

Once prized as a source of vital minerals, especially nickel, iron ore, and phosphates, this remote area is now the center of extensive oil and natural gas extraction. With temperatures rising in the Arctic twice as fast as anywhere else on the planet and sea ice retreating ever farther north every year, offshore fossil-fuel exploration has become increasingly viable. As a result, large reserves of oil and natural gas — the very fuels whose combustion is responsible for those rising temperatures — have been discovered beneath the Barents Sea and both countries are seeking to exploit those deposits. Norway has taken the lead, establishing at Hammerfest in Finnmark the world’s first plant above the Arctic Circle to export liquified natural gas. In a similar fashion, Russia has initiated efforts to exploit the mammoth Shtokman gas field in its sector of the Barents Sea, though it has yet to bring such plans to fruition.

For Russia, even more significant oil and gas prospects lie further east in the Kara and Pechora Seas and on the Yamal Peninsula, a slender extension of Siberia. Its energy companies have, in fact, already begun producing oil at the Prirazlomnoye field in the Pechora Sea and the Novoportovskoye field on that peninsula (and natural gas there as well). Such fields hold great promise for Russia, which exhibits all the characteristics of a petro-state, but there’s one huge problem: the only practical way to get that output to market is via specially-designed icebreaker-tankers sent through the Barents Sea past northern Norway.

The exploitation of Arctic oil and gas resources and their transport to markets in Europe and Asia has become a major economic priority for Moscow as its hydrocarbon reserves below the Arctic Circle begin to dry up. Despite calls at home for greater economic diversity, President Vladimir Putin’s regime continues to insist on the centrality of hydrocarbon production to the country’s economic future. In that context, production in the Arctic has become an essential national objective, which, in turn, requires assured access to the Atlantic Ocean via the Barents Sea and Norway’s offshore waters. Think of that waterway as vital to Russia’s energy economy in the way the Strait of Hormuz, connecting the Persian Gulf to the Indian Ocean, is to the Saudis and other regional fossil-fuel producers.

The Military Dimension

No less than Russia’s giant energy firms, its navy must be able to enter the Atlantic via the Barents Sea and northern Norway. Aside from its Baltic and Black Sea ports, accessible to the Atlantic only via passageways easily obstructed by NATO, the sole Russian harbor with unfettered access to the Atlantic Ocean is at Murmansk on the Kola Peninsula. Not surprisingly then, that port is also the headquarters for Russia’s Northern Fleet — its most powerful — and the site of numerous air, infantry, missile, and radar bases along with naval shipyards and nuclear reactors. In other words, it’s among the most sensitive military regions in Russia today.

Given all this, President Putin has substantially rebuilt that very fleet, which fell into disrepair after the collapse of the Soviet Union, equipping it with some of the country’s most advanced warships. In 2018, according to The Military Balance, a publication of the International Institute for Strategic Studies, it already possessed the largest number of modern cruisers and destroyers (10) of any Russian fleet, along with 22 attack submarines and numerous support vessels. Also in the Murmansk area are dozens of advanced MiG fighter planes and a wide assortment of anti-aircraft defense systems. Finally, as 2019 ended, Russian military officials indicated for the first time that they had deployed to the Arctic the Kinzhal air-launched ballistic missile, a weapon capable of hypersonic velocities (more than five times the speed of sound), again presumably to a base in the Murmansk region just 125 miles from Norway’s Finnmark, the site of the upcoming NATO exercise.

More significant yet is the way Moscow has been strengthening its nuclear forces in the region. Like the United States, Russia maintains a “triad” of nuclear delivery systems, including intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), long-range “heavy” bombers, and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). Under the terms of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), signed by the two countries in 2010, the Russians can deploy no more than 700 delivery systems capable of carrying no more than 1,550 warheads. (That pact will, however, expire in February 2021 unless the two sides agree to an extension, which appears increasingly unlikely in the age of Trump.) According to the Arms Control Association, the Russians are currently believed to be deploying the warheads they are allowed under New START on 66 heavy bombers, 286 ICBMs, and 12 submarines with 160 SLBMs. Eight of those nuclear-armed subs are, in fact, assigned to the Northern Fleet, which means about 110 missiles with as many as 500 warheads — the exact numbers remain shrouded in secrecy — are deployed in the Murmansk area.

For Russian nuclear strategists, such nuclear-armed submarines are considered the most “survivable” of the country’s retaliatory systems. In the event of a nuclear exchange with the United States, the country’s heavy bombers and ICBMs could prove relatively vulnerable to pre-emptive strikes as their locations are known and can be targeted by American bombs and missiles with near-pinpoint accuracy. Those subs, however, can leave Murmansk and disappear into the wide Atlantic Ocean at the onset of any crisis and so presumably remain hidden from U.S. spying eyes. To do so, however, requires that they pass through the Barents Sea, avoiding the NATO forces lurking nearby. For Moscow, in other words, the very possibility of deterring a U.S. nuclear strike hinges on its ability to defend its naval stronghold in Murmansk, while maneuvering its submarines past Norway’s Finnmark region. No wonder, then, that this area has assumed enormous strategic importance for Russian military planners — and the upcoming Cold Response 2020 is sure to prove challenging to them.

Washington’s Arctic Buildup

During the Cold War era, Washington viewed the Arctic as a significant strategic arena and constructed a string of military bases across the region. Their main aim: to intercept Soviet bombers and missiles crossing the North Pole on their way to targets in North America. After the Soviet Union imploded in 1991, Washington abandoned many of those bases. Now, however, with the Pentagon once again identifying “great power competition” with Russia and China as the defining characteristic of the present strategic environment, many of those bases are being reoccupied and new ones established. Once again, the Arctic is being viewed as a potential site of conflict with Russia and, as a result, U.S. forces are being readied for possible combat there.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo was the first official to explain this new strategic outlook at the Arctic Forum in Finland last May. In his address, a kind of “Pompeo Doctrine,” he indicated that the United States was shifting from benign neglect of the region to aggressive involvement and militarization. “We’re entering a new age of strategic engagement in the Arctic,” he insisted, “complete with new threats to the Arctic and its real estate, and to all of our interests in that region.” To better protect those interests against Russia’s military buildup there, “we are fortifying America’s security and diplomatic presence in the area… hosting military exercises, strengthening our force presence, rebuilding our icebreaker fleet, expanding Coast Guard funding, and creating a new senior military post for Arctic Affairs inside of our own military.”

The Pentagon has been unwilling to provide many details, but a close reading of the military press suggests that this activity has been particularly focused on northern Norway and adjacent waters. To begin with, the Marine Corps has established a permanent presence in that country, the first time foreign forces have been stationed there since German troops occupied it during World War II. A detachment of about 330 Marines were initially deployed near the port of Trondheim in 2017, presumably to help guard nearby caves that contain hundreds of U.S. tanks and combat vehicles. Two years later, a similarly sized group was then dispatched to the Troms region above the Arctic Circle and far closer to the Russian border.

From the Russian perspective, even more threatening is the construction of a U.S. radar station on the Norwegian island of Vardø about 40 miles from the Kola Peninsula. To be operated in conjunction with the Norwegian intelligence service, the focus of the facility will evidently be to snoop on those Russian missile-carrying submarines, assumedly in order to target them and take them out in the earliest stages of any conflict. That Moscow fears just such an outcome is evident from the mock attack it staged on the Vardø facility in 2018, sending 11 Su-24 supersonic bombers on a direct path toward the island. (They turned aside at the last moment.) It has also moved a surface-to-surface missile battery to a spot just 40 miles from Vardø.

In addition, in August 2018, the U.S. Navy decided to reactivate the previously decommissioned Second Fleet in the North Atlantic. “A new Second Fleet increases our strategic flexibility to respond — from the Eastern Seaboard to the Barents Sea,” said Chief of Naval Operations John Richardson at the time. As last year ended, that fleet was declared fully operational.

Deciphering Cold Response 2020

Exercise Cold Response 2020 must be viewed in the context of all these developments. Few details about the thinking behind the upcoming war games have been made public, but it’s not hard to imagine what at least part of the scenario might be like: a U.S.-Russian clash of some sort leading to Russian attacks aimed at seizing that radar station at Vardø and Norway’s defense headquarters at Bodø on the country’s northwestern coast. The invading troops will be slowed but not stopped by Norwegian forces (and those U.S. Marines stationedin the area), while thousands of reinforcements from NATO bases elsewhere in Europe begin to pour in. Eventually, of course, the tide will turn and the Russians will be forced back.

No matter what the official scenario is like, however, for Pentagon planners the situation will go far beyond this. Any Russian assault on critical Norwegian military facilities would presumably be preceded by intense air and missile bombardment and the forward deployment of major naval vessels. This, in turn, would prompt comparable moves by the U.S. and NATO, probably resulting in violent encounters and the loss of major assets on all sides. In the process, Russia’s key nuclear retaliatory forces would be at risk and quickly placed on high alert with senior officers operating in hair-trigger mode. Any misstep might then lead to what humanity has feared since August 1945: a nuclear apocalypse on Planet Earth.

There is no way to know to what degree such considerations are incorporated into the classified versions of the Cold Response 2020 scenario, but it’s unlikely that they’re missing. Indeed, a 2016 version of the exercise involved the participation of three B-52 nuclear bombers from the U.S. Strategic Air Command, indicating that the American military is keenly aware of the escalatory risks of any large-scale U.S.-Russian encounter in the Arctic.

In short, what might otherwise seem like a routine training exercise in a distant part of the world is actually part of an emerging U.S. strategy to overpower Russia in a critical defensive zone, an approach that could easily result in nuclear war. The Russians are, of course, well aware of this and so will undoubtedly be watching Cold Response 2020 with genuine trepidation. Their fears are understandable — but we should all be concerned about a strategy that seemingly embodies such a high risk of future escalation.

Ever since the Soviets acquired nuclear weapons of their own in 1949, strategists have wondered how and where an all-out nuclear war — World War III — would break out. At one time, that incendiary scenario was believed most likely to involve a clash over the divided city of Berlin or along the East-West border in Germany. After the Cold War, however, fears of such a deadly encounter evaporated and few gave much thought to such possibilities. Looking forward today, however, the prospect of a catastrophic World War III is again becoming all too imaginable and this time, it appears, an incident in the Arctic could prove the spark for Armageddon.

Michael T. Klare, a TomDispatch regular, is the five-college professor emeritus of peace and world security studies at Hampshire College and a senior visiting fellow at the Arms Control Association. He is the author of 15 books, including the just-published All Hell Breaking Loose: The Pentagon’s Perspective on Climate Change (Metropolitan Books), on which this article is based.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel (the second in the Splinterlands series) Frostlands, Beverly Gologorsky’s novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt’s A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power and John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II.

Copyright 2020 Michael T. Klare