By Antony Dapiran and Stuart Leavenworth, McClatchy Foreign Staff (TNS)

HONG KONG — Police cleared Hong Kong’s government center Thursday of pro-democracy protesters. Now the question becomes: Is this the final chapter of the challenge to Beijing and its all-powerful control of the former British colony or just the beginning?

The police faced little resistance from demonstrators as they demolished tents and pushed out people from the city’s largest protest site, in Hong Kong’s Admiralty district. Street occupations there, surrounding Hong Kong’s government complex, have gripped and gradually dismayed the city’s residents for 75 days.

Yet as they left, protest leaders and rank-and-file demonstrators offered few clues of what might come next. Some wept. Some said they were ready to move on. Some said it was time to plan a new phase of action.

“The movement has lost the support of the people,” said a protester named Phoebe, who declined to give her surname and said she had been there every day since the protests began. “If they tried to clear earlier, maybe there would have been more resistance, but now everyone is tired.”

Others were more defiant, frustrated that more hadn’t been gained by 11 weeks of sacrifice, including clashes with police and street camping under thunderstorms. Some said more direct action could be expected — if not immediately, then in coming months.

Acting on a court order, bailiffs, police and demolition crews began removing barricades at roughly 10:30 a.m. local time outside the city’s government buildings. By late afternoon, they had cleared a vast area once occupied by hundreds of tents. By the evening, traffic was restored to some of the streets that protesters had blocked off.

Leaders of the main student protest groups, Scholarism and the Hong Kong Federation of Students, had urged protesters to comply peacefully with the removal order. The vast majority did.

A group of roughly 70 demonstrators sat down in the street and waited for police to act. The police arrested them in phases late in the afternoon and into the evening.

As most protesters left of their own accord, police checked their IDs and recorded their names for possible future prosecution. According to Hong Kong news media, two shifts of about 7,000 police officers were to be deployed in the clearance.

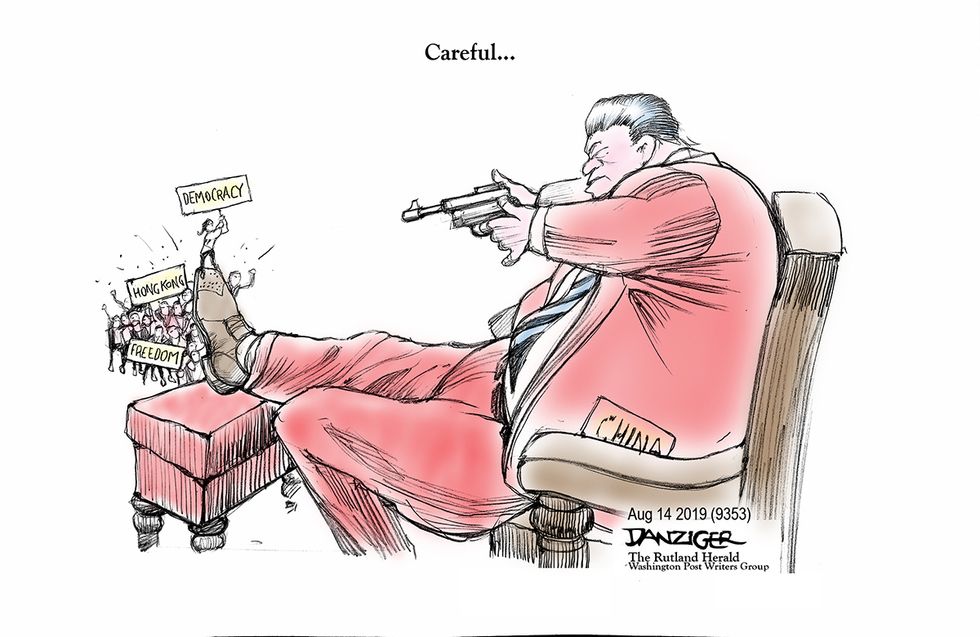

Students and pro-democracy activists had been protesting a decision by Beijing to screen candidates who will run in 2017 for the post of Hong Kong’s chief executive. Protesters want a system of open nominations, as opposed to candidates put forward by a committee stacked with people loyal to Beijing.

After police used tear gas on a small group of protesters Sept. 28, thousands had rushed in and started occupying the Admiralty site, as well as two other locations in the city. The demonstrations had drawn international attention, but as the weeks passed, public support waned and divisions emerged among factions of the “Umbrella Movement,” so called because of the umbrellas the protesters used to ward off the tear gas.

Fernando Cheung, a Hong Kong Legislative Council member who has been supporting the students, said the protests had highlighted the generation gap in Hong Kong, with young people much more frustrated about their prospects and much more willing to rebel against the system.

Asked what the next step is for the movement, Cheung responded: “We need to recuperate, reorganize ourselves. We need to look at other options.” One of those options, he said, is for the Legislative Council to press Chief Executive C.Y. Leung, also known as Leung Chun-ying, to seek broader reforms from Beijing.

In recent weeks, bus and taxi groups had obtained court injunctions against the street occupations, prompting bailiffs and police to act. On Thursday, a bus company employee who gave his name only as Chau expressed satisfaction as the police cleared the site.

“It is good that life is getting back to normal. Opening the roads is the most important thing,” he said. “This has brought a lot of inconvenience to a lot of people. If they go and demonstrate in a park, that is fine.”

Although the number of protesters had fluctuated over the last two months, the Admiralty site had grown into a mini-city. Demonstrators built a large covered “study center” — with tables, chairs, lights and Wi-Fi — for students to do their homework. New protest artwork popped up daily. All of that is gone now, either removed by demonstrators for safekeeping or taken down by clearance crews.

Protesters sought to preserve some of what had taken place here, including hundreds of sticky notes expressing support for the movement that had festooned what became known as “Lennon’s Wall,” named for the late John Lennon of the Beatles. On Thursday, amateur archivists took down nearly all the notes, an attempt to save them from the garbage bin.

With traffic expected to be restored to the area Friday, the debate continues on the Umbrella Movement and its impact. Has it planted the seeds of democracy in a corner of China, a former British colony? Or is it a futile effort to budge a Communist Party that has no intention of experimenting with governance that might challenge its absolute rule?

Rose Tang, a New York-based human rights activist who participated in the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests in Beijing, is one who thinks that history was made. She traveled to Hong Kong last week to witness the demonstrations.

“What this movement has achieved the most is that Hong Kongers have found their identity,” she said. “The whole movement has been incredibly creative, imaginative, romantic and humorous.”

Tang said it was the first time since Tiananmen that China’s one-party government had been openly challenged by street protests.

“This is the beginning of a great movement, of a new phase of the movement,” she added. “The seeds of the Umbrella Revolution have been buried, and when the seeds are buried, they do not disappear. They sprout and bloom.”

___

(Dapiran is a McClatchy special correspondent. Leavenworth reported from Beijing.)

Photo: A protester yells as police and demolition crews clear the main Hong Kong protest site in China on Thursday, Dec. 11, 2014. Pro-democracy protesters have occupied this site, near government headquarters, since Sept. 28. They are defying Beijing to seek a more open election system to choose Hong Kong’s chief executive in 2017. (Antony Dapiran/McClatchy DC/TNS)