Liberated By Grace

WASHINGTON — For those who see religion as primarily an opiate, African-American Christianity offers a riposte. For those who see Christianity itself as a faith that encourages quiescence and conservatism, the tradition of the black church is a sign of contradiction.

Over the last few weeks, white Americans who never paid much attention to the religious convictions of their brothers and sisters of color have received an education. As has happened before in our history, much of this learning is prompted by tragedy, beginning with the murder of nine people at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston and also a series of church burnings, not all of which have been explained.

The African-American Christian tradition has been vital in our history for reasons of the spirit but also as a political seedbed of freedom and a reminder that the Bible is a subversive book. In the days of slavery, masters emphasized the parts of Scripture that called for obedience to legitimate authority. But the slaves took another lesson: that the authority they were under was not legitimate, that the Old Testament prophets and Exodus preached liberation from bondage, and that Jesus himself took up the cry to “set the oppressed free” with passion and conviction unto death.

The church was also a free space for African-Americans, not unlike the Catholic Church in Poland under communism, which provided dissidents with room to maneuver. Even when segregationist Jim Crow laws were at their most oppressive, their churches provided places where African-Americans could pray and ponder, organize and debate, free of the restrictions imposed outside their doors by the white power structure, to borrow a phrase first widely heard in the 1960s.

It was thus no accident that the black church was at the center of the civil rights movement. And it’s precisely their role as an oasis from repression that the churches became the object of burnings and bombings. The freedom enabled by sacred and inviolable space has always been dangerous to white supremacy.

But the church is about more than politics, and a liberating Gospel is also a Gospel of love. The family members of those slain at Emanuel AME astonished so many Americans by offering forgiveness to the racist shooter, Dylann Roof.

There was nothing passive about this act of graciousness, for forgiveness is also subversive. By offering pardon to Roof, said the Rev. Cheryl Sanders, professor of Christian Ethics at Howard University’s Divinity School, the families of the victims demonstrated that there was “something radically different” about their worldview. The act itself “was a radical refusal to conform to what’s expected of you. It’s a way to avoid hating back.” They were, she said, following Jesus, who declared on the cross: “Forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

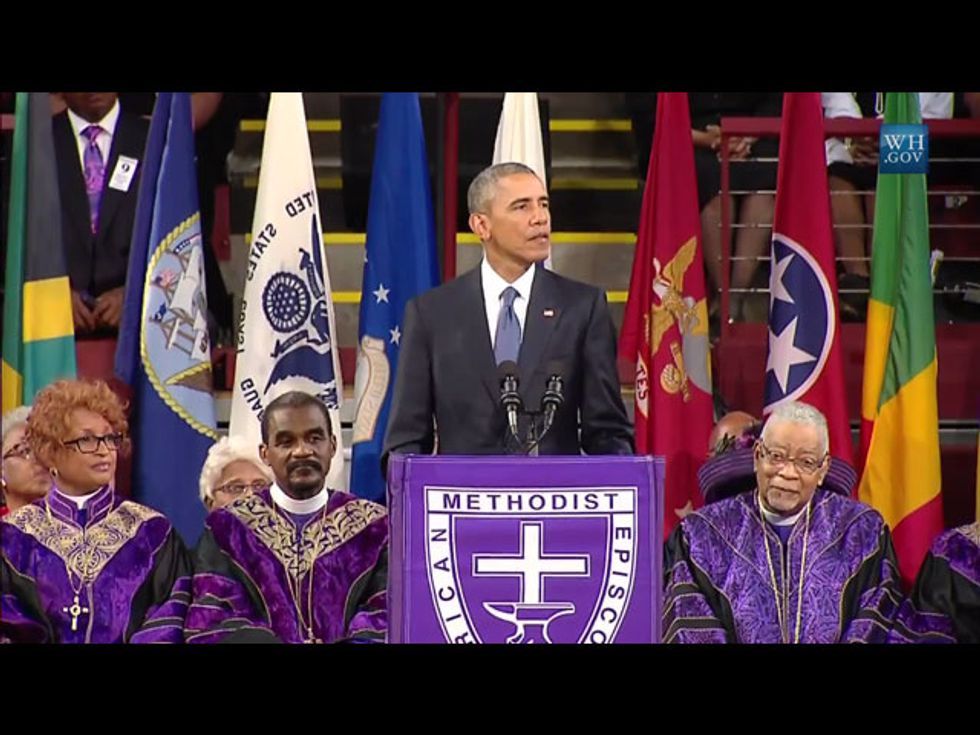

President Obama created an iconic moment when he sang “Amazing Grace” at the funeral of the Rev. Clementa Pinckney. Few hymns have greater reach, not only across denominational lines, but also to nonbelievers who can identify with its celebration of personal conversion and transformation — of being lost and then found.

But Sanders, who is also pastor of the Third Street Church of God in Washington, D.C., points out that the hymn has particular meaning to African-Americans. John Newton, who wrote it in the 1770s, was a slave-ship captain who converted to Christianity, turned his back on his past (“saved a wretch like me”) and became a pastor. Newton eventually joined William Wilberforce’s Christian-inspired movement to abolish the slave trade in the British Empire.

The African-American church tradition teaches that Christianity’s message resonates far beyond the boundaries of any racial or ethnic community, yet also shows that particular groups of Christians give it their own meaning. The idea that all are divinely endowed with equal dignity is a near-universal concept among Christians. But as Sanders says, an insistence on “the dignity and humanity of people in the sight of God” has exceptional power to those who have suffered under slavery and segregation.

“The whole story to them is ‘I can be free,'” she says. “If I am poor, poverty doesn’t invalidate my humanity. If I am humbled, I can be lifted up by God.”

And the scholar Jonathan Rieder noted in his book about Martin Luther King Jr.’s ministry, “The Word of the Lord Is Upon Me,” that the Resurrection and the Exodus stories were rich sources of hope, especially in the movement’s darkest moments. “God will make a way out of no way” was King’s answer to those whose spirits were flagging.

No shootings, no bombings, no fires can destroy this faith.

E.J. Dionne’s email address is ejdionne@washpost.com. Twitter: @EJDionne. (

Photo: Allen Forrest via Flickr