We Can Attack Global Warming Without Donald Trump

It would be nice if President-elect Donald Trump took one of the most serious threats to life on earth seriously, but he does not. Trump called global warming a Chinese “hoax” during the campaign, and he’s assigned a science dunce to lead the transition at the Environmental Protection Agency.

The comforting news is that America can move past the black hole of ignorance in Trump’s Washington — or New York or wherever he is. Enlightened state and city governments, as well as the private sector, can provide the leadership. As it happens, they’re already on the case.

Huge example: During the Paris climate change conference last December, Bill Gates organized a handful of billionaires and came up with $15 billion for his Breakthrough Energy Coalition. The group’s mission is to fund research on radical new clean energy technologies.

“Ten guys in a room produced more money than the entire world community of nations in commitment of resources,” Daniel Esty, professor of environmental law and policy at Yale Law School, told me.

“I’m not as sad or crushed as some people (that Trump was elected),” he added. “When the federal government collapses, state governments step up.”

California’s war on greenhouse gases is already 10 years old. Its original goal was to reduce the state’s carbon footprint to the 1990 level by the year 2020. The new goal is to shrink the carbon footprint to 40 percent below the 1990 level by 2030.

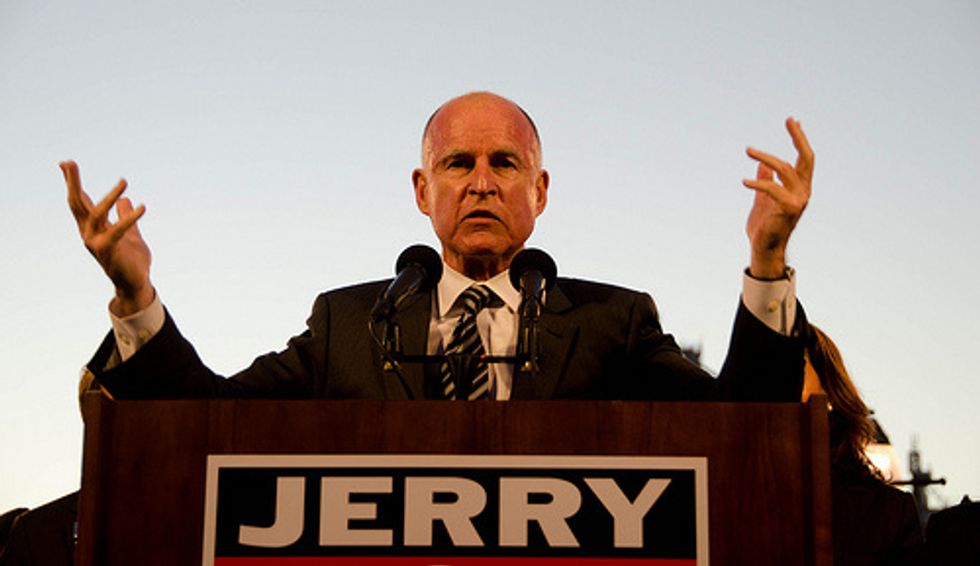

After the election, Gov. Jerry Brown rejected the notion of defeat or backsliding. “We will protect the precious rights of our people and continue to confront the existential threat of our time — devastating climate change,” he announced.

Brown is not without economic firepower. California is the world’s sixth-biggest economy.

Regional compacts in the West, in the Northeast and elsewhere are following California’s lead. There’s also one in South Florida, where “king tides” are now flooding streets on perfectly sunny days.

Can Trump be educated on this issue — or at least tamed by forces he can’t control?

Former French President Nicolas Sarkozy, again running for the office, vows to slap a carbon tax on American imports if Trump pulls us out of the Paris climate deal. Could that happen?

Absolutely, according to Esty. Countries failing to meet international standards that form the base line for fair competition can be punished. And 195 nations have joined the Paris agreement.

Climate change has become a major priority for the U.S. Department of Defense. Rising waters already threaten Navy installations along the mid-Atlantic coast. And as the Arctic ice melts, Russia is opening bases in the region.

Higher temperatures worsen drought in Africa, unleashing mass migrations and spawning terrorists. Adm. Samuel Locklear III has called climate change the “biggest long-term security threat” in the Asia-Pacific region.

Trump may not know this, but China, the biggest producer of greenhouse gases, has been slashing its carbon emissions. How big is this? Ginormous. In the first four months of 2015, China cut emissions by an amount roughly equal to Britain’s entire emissions for the same period.

The smaller carbon footprint is merely a byproduct of China’s effort to clean up its putrid air. Getting rid of carbon emissions also gets rid of dirty air. That’s why states are still going after them even though the greenhouse gases themselves spread evenly around the globe.

As for Trump, he’s done little so far other than to embarrass reality-based Americans. But again, we can work around him.

Last summer, Brown told climate change deniers: “Bring it on. We’ll have more battles, and we’ll have more victories.”

Can Jerry Brown be our alt-president?

Follow Froma Harrop on Twitter @FromaHarrop. She can be reached at fharrop@gmail.com. To find out more about Froma Harrop and read features by other Creators writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators webpage at www.creators.com.

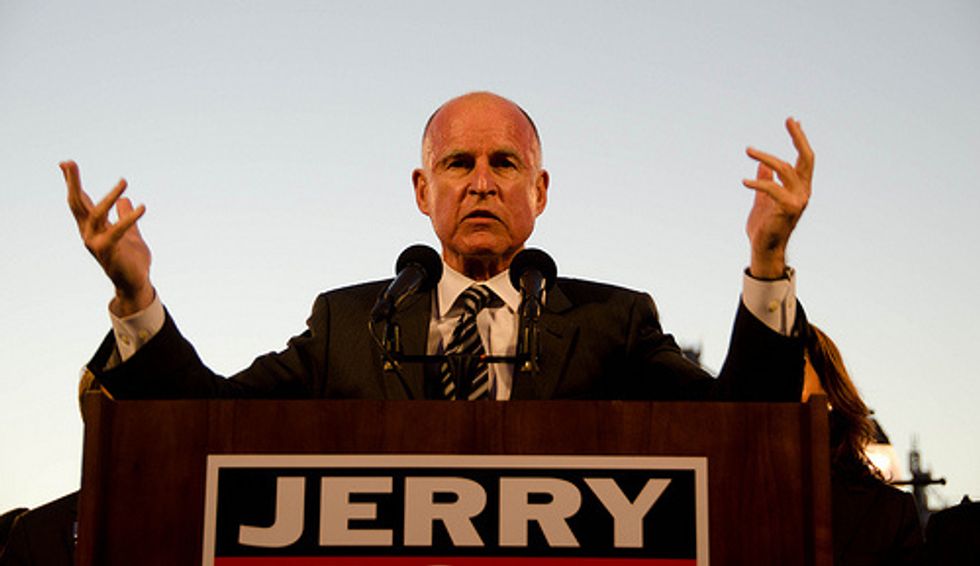

IMAGE: The Eiffel tower is illuminated in green with the words “Paris Agreement is Done”, to celebrate the Paris U.N. COP21 Climate Change agreement in Paris, France, November 4, 2016. REUTERS/Jacky Naegelen