‘The Great War Of Our Time’ Goes Inside The CIA, To A Point

By Tony Perry, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

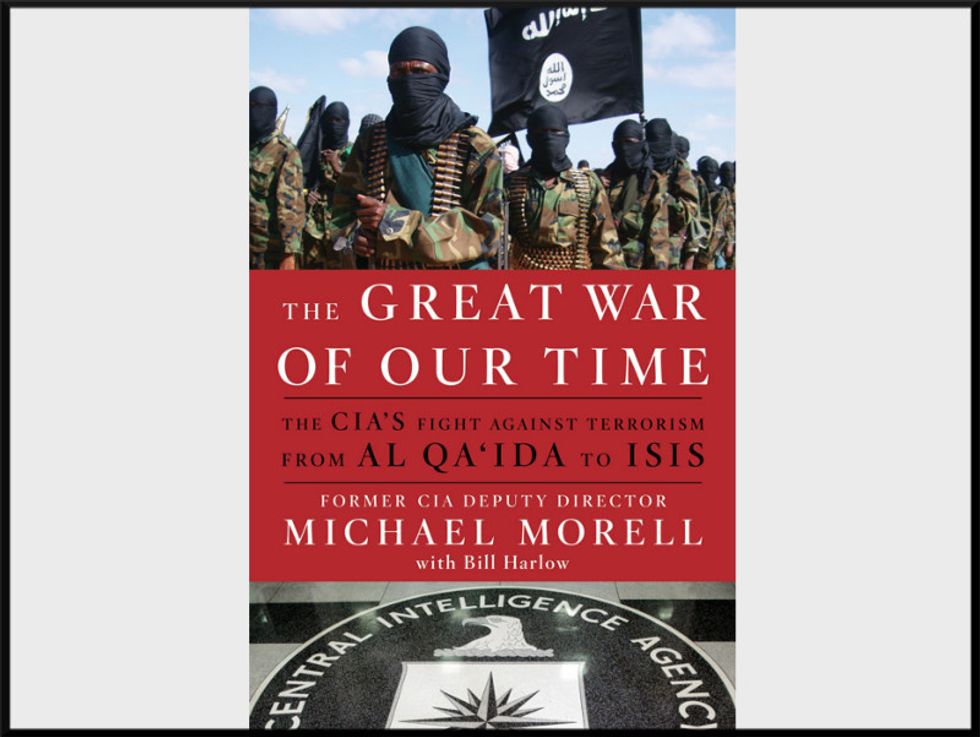

The Great War of Our Time: The CIA’s Fight Against Terrorism — From Al Qa’ida to ISISby Michael Morell, with Bill Harlow; Twelve (384 pages, $28)

___

In his book The Great War of Our Time, former CIA deputy Director Michael Morell explains the blunder that led to Saddam Hussein being deposed and sent him into hiding in a spider hole.

Hussein, Morell writes, had overestimated the U.S. intelligence-gathering capability.

The Iraqi dictator wanted to maintain the bluff that he had weapons of mass destruction to keep “his number one enemy,” Iran, at bay. His mistake was in assuming U.S. intelligence would realize he did not have WMDs and would “eventually lower the (economic) sanctions and, more important, not attack him.”

Among the other nuggets in Morell’s book, subtitled The CIA’s Fight Against Terrorism — From Al Qa’ida to ISIS, is this: Once captured, Hussein grew a beard because he thought it would help him flirt with the nurses. Again, a miscalculation.

For three decades, Morell worked at the CIA, rising to acting director before retiring in 2013; he is now a national-security correspondent for CBS News. He briefed Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama. He was, in CIA lingo, “read into” the top issues of the day, putting him inside “the circle of knowledge.”

The book was vetted by the CIA. Do not expect blockbuster secrets. Or a tough-minded analysis of the agency. Morell’s self-description is that he’s a “Midwestern straight-arrow.”

His analysis of the presidents is standard stuff. Bush was decisive if a bit impetuous. He quotes the commander-in-chief swearing during a briefing: “F*ck diplomacy. We are going to war.”

Obama, Morell said, is thoughtful and cordial but slow to make a decision: “…the president also had a way of making decisions that satisfied competing factions among his national security team.”

Morell is less enamored of former Vice President Dick Cheney, his aide Scooter Libby, former CIA Director Porter Goss and Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina. But even then, his criticism remains low-key.

Much of the book is designed to set the record straight on how pre-Iraq war intelligence got messed up and what happened the night of the 2012 attack in Benghazi, Libya, when the U.S. ambassador and three U.S. personnel were killed and a U.S. diplomatic facility destroyed.

Point by point, Morell takes on the critics, particularly in regard to the accusation that the CIA and White House tried to spin the story with false “talking points” for political purposes. “No committee of Congress that has studied Benghazi,” he declares, “has come to this conclusion.”

Indeed, Morell insists, only one CIA judgment, made within 24 hours of the incident, has proved wrong: the conclusion that the attack was a protest that went violent, not a planned assault.

“CIA should stay out of the talking-point business,” Morell suggests, “especially on issues that are being seized upon for political purposes.”

Still, it is doubtful The Great War will silence those who question the CIA, Presidents Bush and Obama, and former Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton. Within days of the book being published, Morell took to Politico with an essay: “Debunking the Benghazi Myths: It’s Clear Pundits Don’t Understand Intelligence Work.”

On the question of how Osama bin Laden was able to escape from the Tora Bora mountains in late 2001, Morell writes that, “The forces that would have been necessary to box him in, to keep him from fleeing over the border into Pakistan, had simply not been there.”

Other accounts give a different version: that there were sufficient forces there, or close by, including Marines from Camp Pendleton who were at Kandahar, but that an order came from higher authority for the U.S. to back off and let the Afghans take over. If Morell knows anything about this, he’s not telling.

Morell joined the CIA out of college and never stopped being impressed by the organization and its people. CIA employees are “the finest public servants” he knows. CIA analysts are a “terrific group.” That CIA employees drove back to work after the 9/11 attacks was “stunningly patriotic.”

Even the Christmas party at CIA headquarters comes in for praise, particularly during the tenure of Leon Panetta: “If you are in the national security business, it is the place to be. People arrive early and stay late.”

His respect for his former employer aside, Morell admits that the agency was wrong to let then-Secretary of State Colin Powell go to the United Nations with assertions about Hussein and WMDs that were at most estimations, not slam-dunks: “…CIA and the broader intelligence community clearly failed him and the American public.”

In passing, Morell mentions tension between the CIA and the National Security Agency and between CIA station chiefs abroad and the analysts back at Langley, Va. More on that would have been welcome.

More insightful books on the CIA have been and will be written. But an insider’s view, even one with such a mild tone, is a good addition, particularly for those of us not in the “circle of knowledge.”

(c)2015 Los Angeles Times. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.