By Douglas Hanks and Jay Weaver, Miami Herald (TNS)

MIAMI — Jeb Bush was out of the Florida governor’s mansion for less than a year when he signed a $15,000-a-month consulting deal with InnoVida, a Miami startup promising to revolutionize affordable housing with remarkably sturdy and lightweight building panels.

But InnoVida never delivered. Instead, the company crashed amid bankruptcy and fraud investigations that ultimately landed its charming CEO, Claudio Osorio, in federal prison for nearly 13 years.

A bankruptcy trustee went after Bush’s fees, and in 2013 the former two-term governor agreed to pay back more than half of the $470,000 he collected as a consultant between late 2007 and the fall of 2010.

Bush, who also served on InnoVida’s board, was never accused of wrongdoing in Osorio’s Ponzi-like swindle that prosecutors said netted him and other co-conspirators about $50 million. But InnoVida occupies noteworthy real estate in the broad landscape of Bush’s business dealings, since it’s the only one to have ended in the kind of full-blown scandal that occurs when a CEO is led away in handcuffs.

InnoVida’s salacious finale is drawing renewed attention as Bush readies for a presidential run. The Republican touting the power of free enterprise in his “Right to Rise” campaign served on a corporate board that presided over a venture fraught with bogus accounting statements and fictional business deals.

Miami attorney Linda Worton Jackson, who has represented InnoVida creditors in the bankruptcy case, faulted the board of directors for lacking leadership, failing to properly oversee Osorio, and missing warning signs as he dodged questions and provided evasive answers about the company’s finances.

“When someone as prominent as Jeb Bush lends his name to a company, it gives the creditors a level of false security,” Jackson told the Miami Herald. “Creditors assume that he is scrutinizing the company rather than receiving stock and money for simply ratifying each decision by Osorio. This is precisely the reason con artists encourage prominent people to be a part of the fraudulent company.”

A Bush spokeswoman said the former governor had concerns “toward the end of the relationship” about InnoVida’s governance and financial disclosures and took action in 2010 once he realized there was a severe problem at the company. She noted his settlement with the bankruptcy trustee includes language praising his assistance.

“It is now obvious that Mr. Osorio deliberately misled a board of directors of prominent business leaders about his company’s dealings and this is why he is now in jail,” Bush spokeswoman Kristy Campbell said in an email response to questions.

Campbell said that before joining the company as a consultant, the former governor had vetted InnoVida by visiting its Middle East operation and interviewing employees — and “all appeared legitimate.” Bush had also hired an investigator to research Osorio and found “no red flags indicating any criminal or financial wrongdoing.”

But Miami attorney David Nunez, who represented NBA player Carlos Boozer and others after they lost $2.5 million invested in InnoVida, said a thorough probe likely would have revealed Osorio’s “questionable history” at his prior high-flying company, CHS Electronics.

As head of CHS, Osorio built the Miami-based computer distributor into a Fortune 500 company, but it went belly up in 2000 as shareholders accused him in a class-action lawsuit of failing to disclose critical financial information. In a settlement, the company agreed to pay $11.75 million in cash.

Out of public life since January 2007, Bush’s private-sector dealings with InnoVida and other companies are now often cited as a potential political vulnerability. He served five years as a director of Swisher Hygiene, overlapping with a time when the Charlotte-based seller of sanitary supplies issued faulty earnings reports that later had to be restated. Lehman Brothers hired Bush as a consultant in 2007 as the investment bank was heading toward a stunning 2008 bankruptcy that contributed to the global financial crisis.

His former board seat at Tenet Healthcare left Bush with stock holdings valued at $2.4 million last year, equity boosted by the company’s profits under the Affordable Care Act — the signature Obama administration program that Bush continues to slam.

The rise and fall of Osorio’s InnoVida is a classic Miami tale of a connected con man with famous friends, a ritzy waterfront house and a smooth sales pitch. There was also a complex web of corporations and subsidiaries that spanned the globe. Bush signed a finders-fee deal with an InnoVida entity in the Cayman Islands, and said he flew to Dubai to inspect the company’s outpost there.

At the heart of InnoVida’s rise were two key elements. First was a new way to make composite building panels, marketed as “lighter than wood, yet stronger than concrete.” Second, Osorio’s high-profile friends and associates, who seemed to validate not only InnoVida’s prosperity but also a lavish lifestyle that included a Star Island mansion, a Maserati and political fundraisers for Barack Obama and the Clintons.

As the brother of the president when he signed his first InnoVida contract on Nov. 16, 2007, Bush carried the most cachet of Osorio’s celebrity recruits. Alonzo Mourning appeared at InnoVida events for Osorio, retired general Wesley Clark flew to Haiti to pitch the president on InnoVida products after the 2010 earthquake, and Miami condo king Jorge Perez invested with the company and was listed as a director, though he insists he never formally joined the board.

Lawyers pressing their case against InnoVida said Osorio leveraged the fame of associates like Bush to lure in deep-pocketed investors and others with the cash and connections needed to sustain the business.

“Jeb was on the board when I agreed to come on the board,” said Chris Korge, a well-known former lobbyist and Miami International Airport concessionaire who became an InnoVida director in 2009, a year after Bush. Korge went on to become a top investor in the company, and said the presence of Bush, Perez and others gave him comfort. “It wasn’t a bunch of dummies on the board.”

Bush hasn’t offered details on what he did for InnoVida, though his role is broadly outlined in court files linked to InnoVida’s well-publicized demise. His contract was to provide “sales and marketing strategies,” according to a filing by a bankruptcy trustee, and an InnoVida document listed him as a “key manager” entitled to 250,000 stock options. As first reported by The Washington Post, Bush also signed up to pursue investor and sales opportunities in Nigeria, South Africa, Mexico and close to home in Florida.

One 2009 contract between Bush and the Cayman Island-based InnoVida Factories envisioned a company plant in Mexico. If Bush could negotiate a joint venture to build it, he would receive 8 percent of the cash pumped into the investment. Alejandro Aguirre, former publisher of Diario Las Americas in Miami, is listed on the contract as Bush’s contact in Mexico and said the former governor brought “instant credibility” to the would-be venture given his name, fluency in Spanish and familiarity with Mexico.

“Jeb opened up the door for me there” at InnoVida, said Aguirre, adding the deal never worked out “because of the economics in Mexico.”

InnoVida established actual operations: a factory in North Miami Beach and another in Dubai, which Bush said he visited before signing on with the company. Commercial developer O. Ford Gibson, a former Bush colleague, said he was excited enough about InnoVida’s technology that he flew around Florida trying to land construction deals for portable classrooms until the company’s panels failed a high-heat test.

The company did land some high-profile business, including a $10 million loan pledge from a U.S. government agency to build low-cost housing in Haiti and partnering with Royal Caribbean to build a school on land the cruise company controlled on the earthquake-battered island. But bankruptcy court records show that Osorio used federal money to pay back some of his early investors, not for the Haiti housing project.

Court records show that the Venezuelan-born Osorio pumped up the business’s financial health and prospects to investors and board members, then used company revenue to fund his living expenses. When InnoVida’s balance sheet showed $35 million in cash, the company really had less than $200,000 on hand, according to a Securities and Exchange Commission complaint. Over the course of four years, prosecutors said in charging documents, Osorio raised about $50 million from investors and lenders, and spent a large chunk of it on himself and his family, including his wife, Amarilis, an “unindicted co-conspirator.”

No documents show Bush investing any money with InnoVida. Campbell, Bush’s spokeswoman, said the former governor never collected any commissions or finder fees from the company — only consulting earnings.

Campbell said Bush told InnoVida management “several times” that it needed to provide directors with the company’s audited financial statements. One 2009 email, first reported by the Post, showed Bush following up on a request he apparently made at one of the company’s infrequent board meetings.

“Craig, fine board meeting last Thursday,” Bush wrote in the Sept. 21, 2009, email to InnoVida CFO Craig Toll, who would later be sentenced to four years in prison on federal fraud charges. “(Y)our offer to send me the cash flow information on the company would be appreciated.”

Toll sent back unaudited cash-flow statements, according to the email chain filed as evidence in Toll’s criminal trial. Bush remained on the board for another year, severing his ties in September 2010 after Korge exposed Osorio as lying about major overseas deals in the Middle East and China that were supposedly on the verge of sending InnoVida’s value soaring tenfold.

InnoVida began to unravel when Korge, the largest local investor, became suspicious. The owner of NewsLink, which runs restaurants and shops at MIA, invested $4 million with InnoVida — about $3 million of it borrowed from friend Rodney Barreto, a partner in one of Miami-Dade’s top lobbying firms. Korge, also a lawyer, said Osorio would cancel meetings to make last-minute trips overseas to land new investor dollars.

When the money never materialized, Korge grew suspicious and hired a private investigator to tail Osorio. When the CEO said he was in China, the detective spotted him at lunch with his wife in Miami Beach.

Korge, a major Democratic fundraiser backing Hillary Clinton in 2016, said he sought out Bush as his first ally on the board, and the two held conference calls with their individual lawyers to plot “what we could do as board members of a private, closely held company to get to the truth and protect all the investors.”

“I think Jeb behaved in an honorable, stand-up way,” Korge said.

After Korge raised the alarm about InnoVida, Bush decided it was time to cut his ties to Osorio and his company. Korge said he and the former governor planned a showdown at a board meeting called for Sept. 16, 2010.

The two men met in the parking lot and strode together toward the front door of the North Miami Beach facility. But Korge expected trouble. Earlier that day, in a meeting with shareholders (which included Korge, an investor, but not Bush) Osorio had used his controlling interest to vote off all the board members beside himself and two executives close to him.

At the entrance, Osorio allowed Bush to pass but told Korge to wait outside, Korge said.

“He was polite,” Korge said. “I told him: ‘You’re wrong. I have a right to come in.'”

Inside the conference room, Bush took his seat at the table. Fellow director Oscar Seikaly, an insurance executive, said the board members were expecting the long-awaited audited financial reports. “Claudio had promised to present them to the board,” Seikaly said. “But he danced around the subject. That was a red flag.”

Campbell said Bush ended his relationship with InnoVida on Sept. 19, 2010. And four days later, Korge filed a lawsuit that ultimately pushed InnoVida into bankruptcy. The federal criminal investigation followed, with Osorio pleading guilty in 2013 to three conspiracy offenses involving wire fraud and money laundering.

Bush’s Coral Gables firm, Jeb Bush and Associates, agreed to pay back $270,000 to the bankruptcy court as part of a trustee’s efforts to “claw back” money owed to creditors and others in the Chapter 7 liquidation proceedings. Unlike other settlements in the case, Bush’s agreement included a “non-disparagement” clause that limits what the bankruptcy trustee can say about the former governor.

The InnoVida bankruptcy trustee’s lawyers, Mark Meland, Michael Budwick and Daniel Gonzalez, declined to comment for this story, citing the clause. Court records show they have assisted the trustee in recovering a total of $4.3 million from InnoVida payouts to 46 parties, including other board members, investors, credit card companies and Osorio’s lawyer.

Bush’s settlement fell roughly in the middle of the roster of recoveries. American Express cut a check for $740,000 after collecting more than $3 million in credit card payments from Osorio’s family account. Perez, CEO of the Related Group, paid back $70,000. That was a large chunk of the $100,000 that InnoVida paid him, which a spokeswoman said was a refund of Perez’s investment in the company.

Miami defense attorney Humberto Dominguez, who represented Osorio in his criminal prosecution, said the disgraced CEO presided over a legitimate business that was represented as being much more successful than it actually was because Osorio was “overzealous” with the books.

In negotiating a plea deal with Osorio, Dominguez said implicating a famous politician like Bush would have been tempting for any defendant looking for leverage with prosecutors. He said they pressed Osorio on Bush’s role.

Osorio “had every incentive in the world to serve him on a platter,” Dominguez said. “He didn’t. He said this guy didn’t know.”

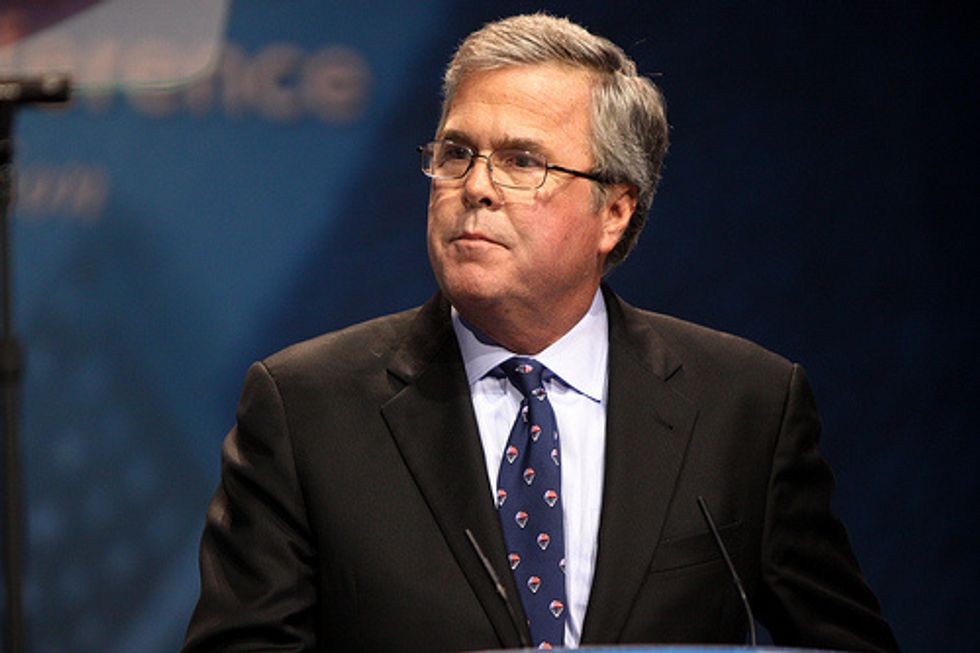

Photo: Gage Skidmore via Flickr