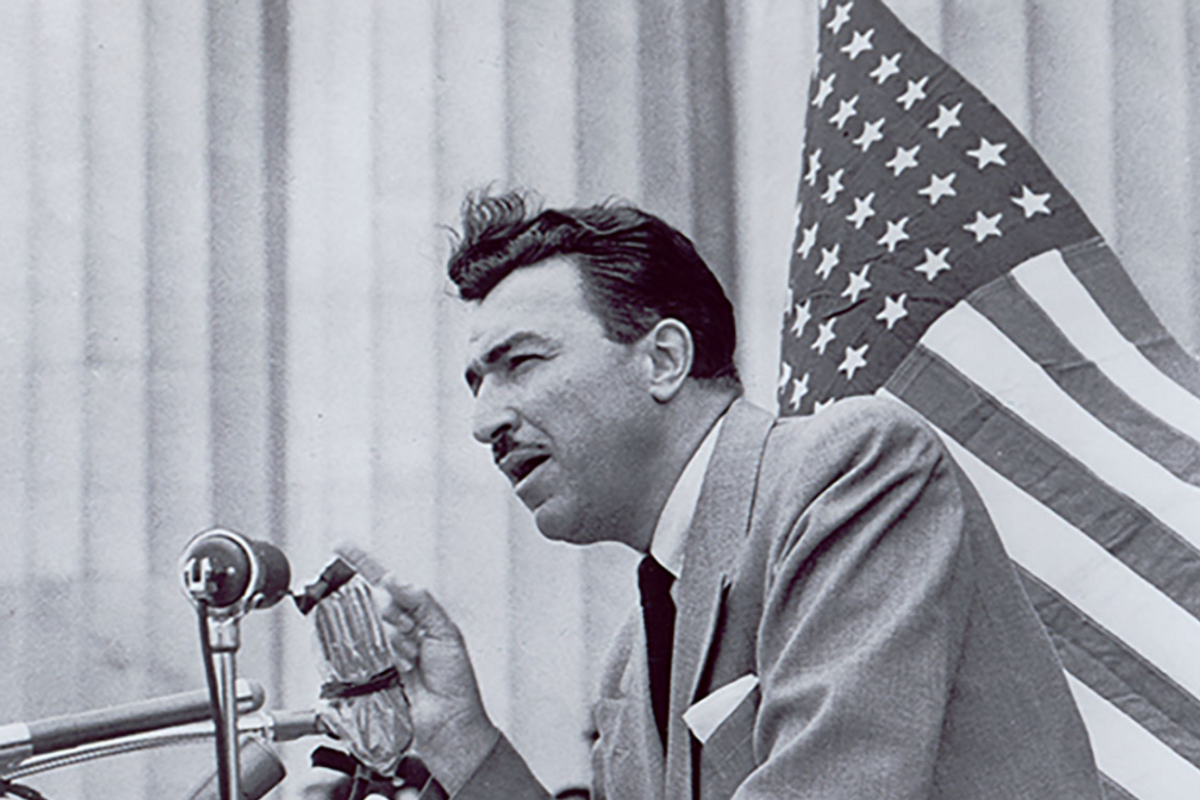

Rep. Adam Clayton Powell Jr. at the U.S. Capitol in 1955

What follows is an excerpt from What It Took to Win: A History of the Democratic Party (Farrar, Straus and Giroux): Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. was the most prominent Black politician in the nation from his first election to Congress from Harlem in 1944 until his defeat in the Democratic primary in 1970. Powell always believed it was essential to build a movement that could pressure politicians to grant the demands of African-Americans and their allies. Today, the tension between grassroots progressives and party leaders remains a central element of Democratic politics.

The legislative branch . . . must immediately change its childish, immature, compromising, 19th century attitude and not just become a part of the 20th century world but a leader. — Rep. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., 1955

The results of the 1948 election came as a relief to Democrats who assumed throughout the campaign that Truman would lose. Victory did little, however, to relax tensions among the leaders of the constituencies most critical to the party’s fortunes. African American voters, their numbers swelled by wartime migrants to northern cities, had greater influence than ever before. There had been only 17 Black delegates at the Philadelphia convention. Yet if those Black people able to vote had cast a large number of their ballots for third-party candidate Henry Wallace or had stayed home, Thomas Dewey would have slipped into the White House. Still, the Democrats’ leaders in Congress, most of whom were Southerners, offered them no legislative gratitude. African Americans would have to engage in disruptive talk and actions against the likes of Bull Connor if they hoped to win their constitutional rights and more.

To put his fellow Democrats— and the nation—on notice for neglecting the needs of Black people was the political calling of Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. The debonair, charismatic, light-skinned minister of what was then the largest Protestant church in America—established by his father—won a seat on the New York City Council in 1941; three years later, voters in Harlem, “the capital of Black America,” swept him into Congress, unopposed. Powell was the first person of his race ever elected to that body from the Empire State. He joined the only other Black member of Congress—William Dawson, a loyal lieutenant of Chicago’s Democratic machine.

In the middle of the 20th century, freedom activists were beginning a surge that would remake American politics and give Powell the opportunity to become the most powerful Black official in the nation. During World War II, the NAACP had boosted its membership by a stunning 1,000 percent. In Black colleges experiencing the same postwar boom as heavily white ones, students demonstrated against conditions on and off campus, defying administrators fearful of losing funding from Jim Crow legislatures. In tiny wooden churches on the edge of cotton fields as well as impressive structures like Powell’s Abyssinian Baptist Church, a Gothic marvel with soaring stained-glass windows, preachers compared African Americans to the Jews liberated from Pharaoh and often urged them to engage in protests. “What can happen when you play your part?” the Harlem congressman asked in a 1953 sermon. “Moses played his part” when he beseeched God to forgive the Israelites for worshipping the golden calf. “And God relented . . . ‘for thou has found grace in my in my sight, and I know thee by name.’ ”

Never content to be a partisan foot soldier, Powell conducted himself as if he were speaking for every Black citizen inside the most august hall of power in the nation. “They were the disenfranchised, the ostracized, the exploited,” he recalled about the African Americans who wrote to him from every region to share their opinions and solicit his aid. The congressman held his seat for more than a quarter century, eventually rising to the chairmanship of a key House committee.

Yet Powell also earned a reputation as a party maverick by stirring up resistance to Democrats who moved too slowly, or not at all, even as he pushed to enact bills to secure freedom for his people. “Defy law of man when in conflict with law of God,” he wrote in 1963, after protests against segregation rocked the streets of Birmingham, Alabama.

Unfortunately, the man known as “Mr. Civil Rights” could not resist making big trouble for himself in ways that sullied his reputation. Powell carried on a series of quite public adulterous affairs, had to defend himself in court for evading taxes and allegedly libeling a Black constituent, and hired one of his wives to a well-paid job for which she did no work. Inevitably, his enemies used all of it against him. “He demanded his right as an individual,” write two of his biographers, “to indulge himself the same as any other man . . . the right to be as bad as the worst white man.”

Yet Powell also played both the inside and outside games of politics with skill, honing a militant image while simultaneously using his status as the nation’s most influential Black elected official to nudge racial progress forward. He first rose to prominence as a “race man” and a friend of the Marxist left. In 1940, Powell refused to join a committee to celebrate FDR’s birthday to protest the president’s frequent visits to a rehabilitation center in Georgia that refused to treat Black people. He also led a bus boycott in New York that compelled the city to hire more African American drivers. For several years in the middle of the 1940s, Powell published a lively weekly, The People’s Voice, that competed with more established Black periodicals. His staff included a number of journalists who belonged to or were close to the Communist Party; during World War II, the paper took such a benevolent stance toward the USSR that Powell himself joked it was the “Lenox Avenue edition of The Daily Worker.” Yet after the Cold War began, he turned against the Reds and closed the paper down.

In Congress, Powell found a shrewd way to press the cause of equality as well as to boost his own renown. In 1946, he proposed the first of a sequence of “Powell amendments.” Each aimed to withhold federal money from any state that practiced segregation. With the aid of lobbyists from the NAACP, he sought to attach a rider to a bill funding the school lunch program, then repeated the tactic over the next decade to restrict appropriations for military bases and schools. Whether out of conviction or guilt, most northern Democrats and some Republicans voted aye, while southern Democrats predictably voted nay. The amendments sometimes passed the House but died in the Senate.

Yet their significance transcended a mere tally of wins and losses. The Powell amendments “entered the national lexicon” and proved that one lone Democrat had the will and power to compel nearly all-white Congresses to decide whether to keep dodging the moral imperative of their time. In the 1950s, as the Black freedom movement began to grow around the nation, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., was preaching and practicing the kind of forceful strategy that would eventually make legal racism a thing of the past.

In 1952, with their party having lost the White House, quite decisively, for the first time in two decades, prominent Democrats debated how to stage a comeback. Powell and his fellow Black activists urged a renewed assault on Jim Crow. They argued that African American voters, who had stuck with defeated nominee Adlai Stevenson, could shift back toward the GOP if the party repeated the timid stand in its platform and the speeches by its nominee. That would make it all but impossible for Democrats to win back the industrial north. But fear that the solidity of the south was cracking mattered more to the top two Democratic leaders in Congress, both of whom were Texans—Sam Rayburn in the House and his protégé Lyndon Johnson in the Senate.

In May 1954, the Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education compelled every Democrat who had any hope of leading the party or becoming president to make a choice. If Chief Justice Earl Warren and his colleagues were justified in ruling that segregated schools were “inherently unequal,” then one should start enforcing desegregation and, perhaps, follow the same logic to renew attempts to enact a sweeping law guaranteeing the integration of public schools.

After offering no comment for ten days following the decision, Stevenson demonstrated once again his talent for putting elegant prose at the service of a political error—and, in this case, a moral wrong. The South “has been invited” by the court “to share the burden of blueprinting the mechanics for solving the new school problems of non-segregation,” he wrote. Appreciating that region’s “great complexities in race relations,” Stevenson urged the “rest of the country” to “extend the hand of fellowship, of patience, understanding, and assistance to the South in sharing that burden.” It was the kind of empathetic plea a president might have issued after a major hurricane. Stevenson’s biographer calls it “a curious statement from a man widely considered a liberal.”

But even white liberals like Minnesota Senator Hubert Humphrey, who cheered the Brown decision, could imagine no path back to victory that did not include keeping Southern whites in the fold. So most avoided denouncing the Declaration of Constitutional Principles—drafted by Russell and signed by nearly every southern member of Congress in March 1956—which attacked the members of the high court for “a clear abuse of judicial power” that “substituted their personal political and social ideas for the established law of the land.”

Cautious as he was on matters of race and labor, Stevenson won strong admirers for his refusal to adhere to partisan dogma. He inspired well-educated white activists in New York, Chicago, and other big cities to challenge the sway of local machines over appointments and patronage. These “amateur Democrats” were also cheered when their hero proposed negotiating with the USSR to cease the testing of nuclear weapons in the atmosphere. They certainly favored civil rights, but the Black freedom movement had not yet grown large or potent enough to force that issue into the heart of national politics.

In 1956, the odd alliance of liberal idealists and wily Southern pols lifted Stevenson to a string of primary wins and then to a first-ballot victory at the convention, held once again on his home turf in Chicago. That uneasy partnership ensured that, at the start of what everyone knew would be a difficult campaign against a popular incumbent, the grievances of Black people would be largely dismissed or neglected. On opening night, Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts, a top contender for the vice-presidential nomination, narrated a film about the party’s history that was silent about its past racism while praising President Andrew Johnson during Reconstruction for battling the Republican “hot-heads and fanatics” who sought only “vengeance against the South.” A short, abstract section on civil rights appeared at the very end of the party’s very long platform. It said nothing about what specific “efforts to eradicate discrimination based on race, religion, or national origin” Democrats might enact if they won the presidency. Fearful of losing Southern votes, Hubert Humphrey refused to join Reuther and other ADA stalwarts who mounted a failed attempt to place in the platform a vow to enforce the Brown decision.

For the congressman from Harlem, the time had come to mount a protest his party could not ignore. Stevenson opposed the Powell amendments, thought using troops to enforce the Brown decision would be an abuse of federal power, and delayed meeting with the Black lawmaker before spurning him altogether. Powell had routinely attacked Eisenhower, accusing him at one point of wanting to bring back the “good old days of segregation” in the military and other parts of the government. But with a month to go in the campaign, the incumbent enjoyed a massive lead in the polls.

So, on October 11, Powell spoke for half an hour with the president at the White House and emerged to tell the press he was endorsing him for a second term. The Black lawmaker soon organized Independent Democrats for Eisenhower in order to rally “disillusioned” liberals to the cause. The group was stillborn, but Powell did give GOP-funded speeches to huge audiences in six cities across the North and Far West. Back in New York, his fellow Black officeholders denounced his decision; some predicted it would end his career. But Powell won a seventh term with ease, taking almost 70 percent of the vote.

Michael Kazin is author ofWhat It Took to Win: A History of the Democratic Partyand six other books on U.S. history. He is a professor of history at Georgetown University and emeritus co-editor of Dissent.