WASHINGTON — Pope Francis is proving himself to be a genuinely holy man, a brilliant politician and a leader who knows that reform requires a keen understanding of how creating a better future demands sophisticated invocations of the past.

Nothing demonstrated all three traits better than Francis’ announcement that he would make both Pope John Paul II and Pope John XXIII saints. The obvious political analysis here is correct: On the whole, conservative Catholics will cheer swift sainthood for John Paul while progressive Catholics will welcome the news that an overly long process of elevating John to the same status had reached its culmination. One for one side, one for the other — it’s a good formula for harmony, something Catholicism needs right now.

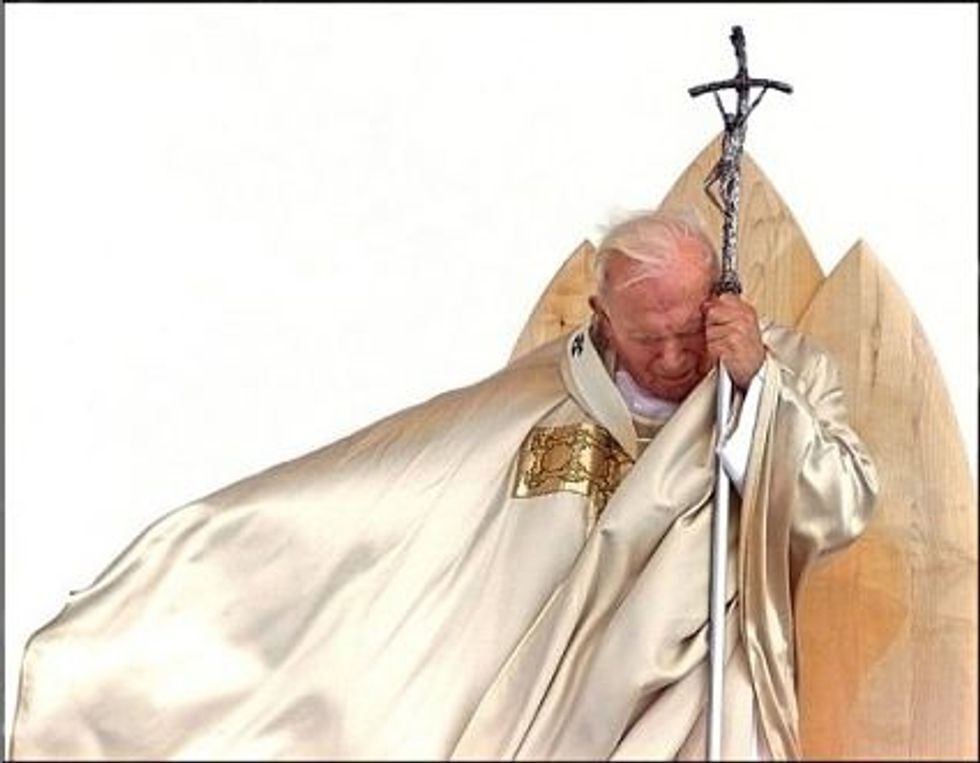

But much more is going on here. Rapid sainthood for John Paul was inevitable, partly because of widespread devotion to him around the church and not simply in its conservative wing. A campaign to sanctify him took off from the moment of his death. Whatever criticisms might be directed his way — on his sluggishness in facing up to the clerical abuse scandal, for example — there should be no denying his standing as a world-historical figure.

His vital role in the collapse of Soviet communism will always be recognized as the product of faith married to shrewd statesmanship. And, speaking personally, getting to cover John Paul’s 1986 visit to a synagogue in Rome where he robustly and decisively condemned anti-Semitism will always endure as one of the most moving experiences of my journalistic life.

But that story is a perfect example of why it was essential to sanctify Popes John and John Paul at the same time. Without Pope John, there would not have been the John Paul we came to admire.

I should acknowledge my interest here since I argued two years ago for just this result. Elevating both popes was the only way to make clear that the sweeping reforms of the Second Vatican Council, called by Pope John, opened the way for John Paul’s greatest achievements. These were, in large part, liberal triumphs involving a commitment to human rights, religious liberty and democracy as well as a stern opposition to religious prejudice and an emphasis on social justice and workers’ rights.

Yet except among the ranks of scholars and older progressive Catholics, Vatican II is so often a dim memory. Moreover, there are conservative voices in the Church that have sought to play down just how important the council was in opening Catholicism to the modern world. Pope John embraced modernity and the lessons it had to teach Catholics even as he was critical of modernity’s failings.

By lifting up John, Pope Francis is telling Catholics to embrace this legacy again — beginning by paying attention to it. In so doing, he will reinforce comparisons already being made between himself and Pope John.

My Georgetown University colleague John Borelli noted recently in The Tablet, the British Catholic magazine, that Francis, like Pope John, has placed a heavy emphasis on social justice, has a deep and long-standing commitment to dialogue with other faiths, and has a similar unpretentious personal style. The National Catholic Reporter has repeatedly linked the two popes and noted a few months ago that Francis expressed his affinity with the pope of Vatican II by saying: “I see him with the eyes of my heart.”

What might have looked like wishful thinking on the part of progressive Catholics for a re-engagement with Pope John’s approach now seems much more like a clear-eyed view of reality.

There will be questions in both cases about Pope Francis’ flexibility with the Church’s requirement that two miracles be attributed to saints. But as retired Newsweek writer Ken Woodward noted in his definitive 1990 book Making Saints, the Church’s process of honoring holy people has always been, shall we say, complex, and not without considerations that might be seen as political. Saints are made, after all, for the enlightenment of the living, and for those who come later.

Woodward followed the sociologist Robert Bellah in noting that telling the stories of saints creates “communities of memory that tie us to the past” and “also turn us toward the future as communities of hope.”

By reminding Catholics of which aspects of the past he wants to celebrate, Francis has pointed the way for a more open, less divided Church that examines the present and looks to the future with hope, not fear.

Photo: AFP/Gabriel Bouys

E.J. Dionne’s email address is ejdionne@washpost.com.